“Bogart was cool: no one used the word then, but it’s the term everyone reaches for now,” writes the literary scholar Joel Dinerstein in American Cool, which he co-authored with photographic scholar and curator Frank H. Goodyear.

Besides Bogie, the reach of those who make cut in this sleek book of photographs interspersed with essays includes Johnny Depp, civil rights protestors, Miles Davis as he appeared on the cover of Ebony, Elvis, Robert Mitchum, Jack Kerouac, Amiri Baraka, Bob Dylan, Anita O’Day, Madonna, Tupac Shakur, Susan Sontag, Selena, and sundry others.

For years, cool fell into the gray zone of semantics like that on which a Supreme Court justice meditated in consideration of pornography: he admitted that he could not define it, but he knew it when he saw it.

We should hope that the Supremes will attend the American Cool exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. (American Cool is the catalog for that exhibition.) This show is an impressive exercise in semantics and a grand slice of national history; the photographs are thoughtfully orchestrated, the ideas behind the concept argued with intelligence and flash.

We can picture the quickening pulse of political and news celebrities in the pagan city on the Potomac, milling about the gallery, wondering why the photographs show none of them. (The Obamas are only mentioned in the text.) But in a city where politics has degenerated into a tawdry suburb of celebrity, the edgy outsider nature of cool doesn’t sync with democracy as reduced to a muddy floor show on the nightly news.

“Cool figures are the successful rebels of American culture,” writes Dinerstein, the James H. Clark Endowed Chair in American Civilization at Tulane University. “To be cool is to have an original aesthetic approach or artistic vision—as an actor, musician, athlete, writer, activist or designer—that either becomes a permanent legacy or stands as a singular achievement.”

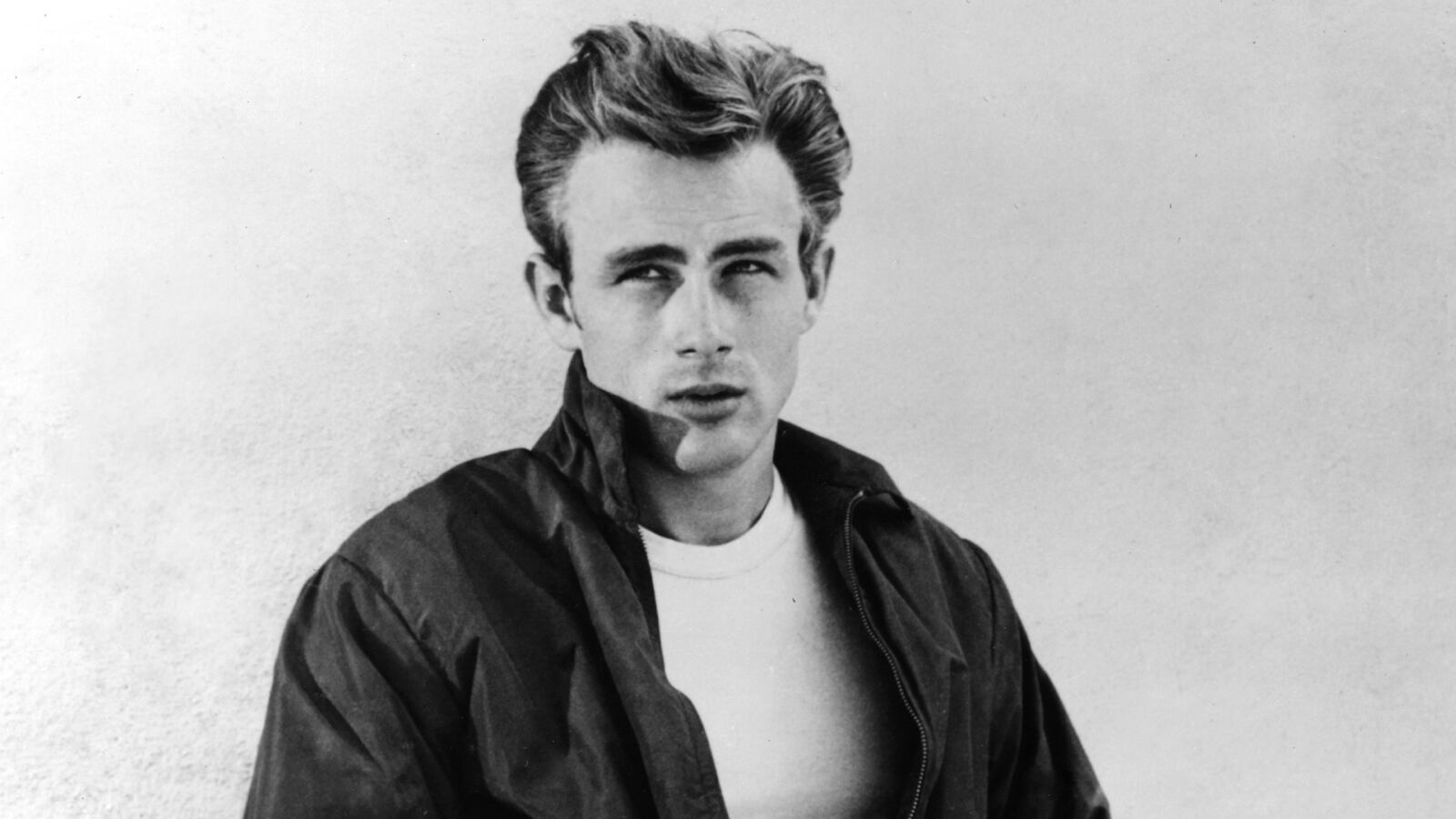

That explains Brando, Duke Ellington, Greta Garbo, Muhammad Ali and of course James Dean. Obama seems to have edged into the text by virtue of being dubbed “Mr. Cool” in a magazine article. The president’s charisma lands him, at least in passing prose, on the same page with an image of Walt Whitman and the front page of Leaves of Grass.

Men far outnumber women in American Cool. “It is rare to find an article, website, or blog post declaring anyone ‘Ms. Cool,’” writes Dinerstein, “despite the plethora of cool women in this book, from Georgia O’Keefe, Bessie Smith, and Dorothy Parker to Patti Smith, Chrissie Hynde, and Missy Elliot.”

The gender tilt lies in “the presumed association between cool and American masculinity,” he notes, and “the persistence of a double standard where independent, sexually confident women are concerned.”

Double standards, of course, are made to be exposed.

American Cool does have curious omissions. Bill Clinton, who played saxophone with sunglasses in 1992 while campaigning on the talk show hosted by Arsenio Hall (who is absolutely cool) and went on to an impeachment drama for his sexual rebellion, did not make the cut. The book does not explain Clinton’s absence, which seems, like, un-cool.

John Wayne had a macho, bravura image that sizzled hot, but he’s in this parade as “the stoic tough guy” who once said, “Mine is a rebellion against the monotony of life.” Cool enough.

But the scandal of this book and exhibition is that Marilyn Monroe is nowhere depicted. One of the sexiest movie stars of all time, the woman who married Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller, is not cool? Says who? And Audrey Hepburn is? And Susan Sarandon, too. No offense to them, but stiff-arming Marilyn Monroe is grounds for—well, not a congressional investigation, we don’t want to get them near this. Let’s settle on a televised debate at NEH.

Hemingway is shown on p. 89, pensive with rifle at a pheasant shoot in Idaho. “He wrote in a terse, clipped style that featured stripped-down dialogue and characters unanchored from society. While he portrayed man as essentially alone, he admired ‘grace under pressure,’ a phrase often considered synonymous with cool,” writes Frank H. Goodyear III, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, who shows a wise hand and keen eye in arrangement of the images in book and exhibit.

Cool as persona and trait arose in the movies and music of the early and middle decades of the last century; it had a strong African-American stamp. Jazz was outsider music that moved mainstream, and then with bebop moved back on the edges. Musicians such as Charlie Parker, Count Basie, and Lester Young exuded the aura of outsider-as-insider. Zora Neale Hurston occupies a page in a photograph as threshold-breaker, justly so. But Wynton Marsalis is nowhere in American Cool. Maybe he’s too inside to go back outside. He’s still a study in cool.

As sports photographers gave an icon like Ali his heft in the popular culture, the oceanic coverage of rock and roll put stars like Jimi Hendrix on the cover of Rolling Stone, which is always cool.

But there are no pictures here of Scarlett Johansson or Halle Berry. The editors chose “a certain triangulation of factors aligned in mysterious balance” on the selection process, which includes a ten-year period of probation or candidacy consideration for a potential Coolite, a time in which status can crash in scandal or somnolently diminish.

“In the next generation it is likely that women will outnumber men for lasting iconic effect and innovative artistic impact,” Dinerstein writes. Those who make the potential list include Esperanza Spalding, Janelle Monáe, Pink, Jennifer Lawrence, Tina Fey, Ani DiFranco, Connie Britton—and (drum roll) Michelle Obama and Rachel Maddow. The First Lady will presumably achieve a plateau of cool once she is out of the White House, no longer bound by media expectations of decorum, and free to speak her piece. Michelle and Barack may be the ultimate cool in politics.

But Rachel Maddow is already cool, many times over, by treating political hypocrisy as a form of farce with intellectual agility you don’t find among other anchorpersons. If anyone in the media stands in the front line of cool, it’s Rachel.

Jon Stewart is in American Cool because he is Jon Stewart. But there is no presence for Steven Colbert. Another mystery. Was it something he said?

“Of the actresses who emerged in the early 1990s with the moxie to walk the line of regular gal and badness,” continues Dinerstein, “there was a cohort including Winona Ryder, Jennifer Lopez, Cameron Diaz, Lucy Liu, Drew Barrymore, Halle Berry, and Uma Thurman. Each of these actresses let the industry shape their careers or cuddled up with the media, became cover girls, or self-destructed.”

There you have it. Media-cuddling can be a kiss-of-anomie for women on the cusp of cool. Men who are cool, or wanna be, can’t be seen as cuddling with the media though they need all the media they can get to stay in the magazines. Goodyear writes learnedly of the role magazines played in capturing those who became cool. Influential photographers who covered jazz, sports, rock, and the movie world were pivotal to this cultural process. Magazine exposure makes a difference, even today as “the paparazzi continue to provide largely unscripted images” that put the cool person in a moment of drama, off-script, in the life s/he enacts.

“Those who convey this magnetic attraction often feel as though they are living in two bodies—one that belongs to the world and another that is their own and often hides in plain sight,” writes Goodyear. His analysis also applies to any number of garden-variety celebrities, even Chris Christie, at least the part about two bodies, or let us say “selves,” one hiding in plain sight.

With smaller photographs arranged through the text, more than half of the book is given over to full or half-page pictures of the anointed cool, with short biographical commentary. You might call this the Hot 100 but Top 100 is probably more appropriate. The range of choices is intriguing.

Number 1 is Walt Whitman, “who first carved out a space for cool by valuing personal experience and bearing over education and experience.” The author of the classic Leaves of Grass was also “a proto-hippie and sensualist who celebrated the dignity of work, a gay man who wrote lyrically of the male body.” Cool then, cool now, cool forever, Mighty Walt.

Fredrick Douglass the great abolitionist, heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson, Georgia O’Keefe, H.L. Mencken, Michael Jordan, Joan Didion, Bill Murray, Angela Davis, Hunter Thompson, Johnny Cash, and Billie Holliday, among others in this sweet romp all stood or stand for life, liberty, and the pursuit of rebellion in American Cool.

Jason Berry’s books include a novel, Last of the Red Hot Poppas.