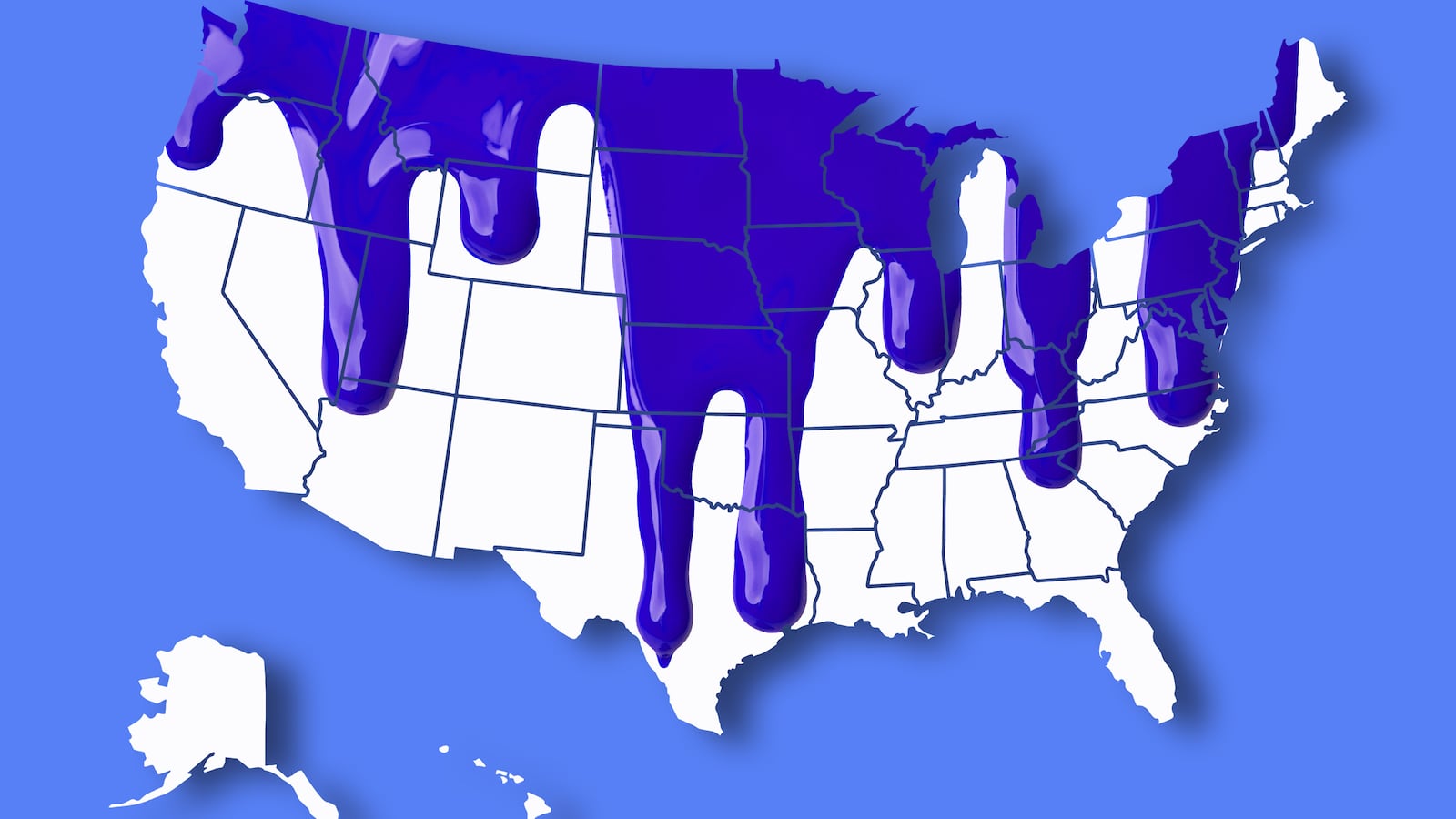

With Republicans clinging to the House of Representatives facing a blue midterm wave, and the 2020 census right around the corner, gerrymandering has suddenly become a hot topic. Democrats are particularly worried that Republican-drawn districts will be too high a wall to breach, no matter how hard they campaign, or how big the wave.

“In 2006, a roughly five-and-a-half-point lead in the national popular vote was enough for Democrats to pick up 31 seats and win back the House majority they had lost to Newt Gingrich,” write Michael Li and Laura Royden of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. “But our research shows that a similar margin of victory in 2018 would most likely net Democrats only 13 seats, leaving the Republicans firmly in charge.”

Imagine a scenario where 2016 (with Hillary Clinton winning the popular vote, but losing the election) is immediately followed by a midterm election where Democrats feel just as cheated. This kind of repeated failure would breed more than just frustration on the left—it would lead to the kind of paranoia that defined the right for the Obama years.

Of course, even if 2020 is an especially good year for Democrats, giving them control of the House of Representatives and the state legislatures that draw the congressional boundaries, gerrymandering won’t end—it will just shift to benefit them. If you don’t believe me—if you think this is a sin exclusive to Republicans—consider the places I have lived.

I’m from western Maryland, the 6th Congressional district that was for many years represented by conservative Republican Roscoe Bartlett (the Supreme Court is currently looking into this). This is culturally more akin to West Virginia or central Pennsylvania than it is to the Maryland of the Baltimore-Washington nexus (I went to college in West Virginia, and my mom now lives in Pennsylvania). This point is buttressed by the fact that Bartlett is now a survivalist living in the Mountain State, and that his heir apparent, former Maryland State Senator Alex Mooney, is now West Virginia Congressman Mooney.

Why did Bartlett go off the grid and why did Mooney have to move across the James Rumsey bridge? Because Democrats decided to give themselves another Congressional seat. As Mother Jones describes it, “Democrats added a strange-looking appendage to the district, reaching all the way down into the affluent Washington DC, suburbs to scoop up Democratic voters. More than 360,000 people were moved out of the district, and nearly as many were moved in. It went from solidly Republican to reliably Democratic; the Cook Political Report identified it as the biggest district swing in the country.”

Today, I live in Alexandria, Virginia, a city that Democrats dominate. In May of 2009, however, one Republican managed to get elected to the six-member City Council. This was apparently too much for Democrats to stomach. One month after his election, the City Council voted to move municipal elections from May to November—an attempt to squash the chances that Republicans could compensate for their numerical disadvantages by organizing to win low-turnout elections. It worked.

But this isn’t peculiar to states where I have resided. The likely Democratic gubernatorial nominee in New Mexico, Rep. Michelle Lujan Grisham, is telling supporters that one selling point for her leaving Congress to run for governor is that “you would be in charge of redistricting.” Meanwhile, the state’s Democratic secretary of state, Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver, was working to change other rules—an attempt to prevent a Republican Congressman running for governor from transferring federal money to his gubernatorial account. Having failed at that, Oliver is now working to bring back straight party voting, which would benefit Democrats in New Mexico.

These were, of course, blatant, anti-democratic, power grabs. But my point isn’t to say “Both sides do it, therefore there’s nothing we can do!”

Politics has to be taken out of the drawing of district lines, to the extent that it can be. The question that everyone is grappling with is how to do that. From proportional representation to nonpartisan redistricting commissions (a handful of states have appointed such commissions, and after the 2020 census, we’ll see how they do), there’s no lack of proposed solutions. One friend of mine thinks the answer is to expand the number of representatives in the House from 435 to 1,000. Who knows?

Whatever the solution is, the actual problem is more fundamental than gerrymandering. The fact that we at the point where something must be done to address a problem that has been around since Elbridge Gerry suggests that there is something more deep-seated at play.

The authors of Why Democracies Die write about the need for mutual toleration and for people in power to exercise “forbearance”—which basically means voluntarily deciding not to run up the score on your opponent—even if you have the power to do so.

It’s asking a lot for a political party, having finally regained power, to do unto others as they would have others do unto them. But if Democrats really mean what they say about how bad gerrymandering is, they will run on platforms for impartial line-drawing. Sadly, that’s the opposite of what at least some of them are hinting at.