After seven months in darkness, the first man-made object to land on a comet has, metaphorically, risen from the dead.

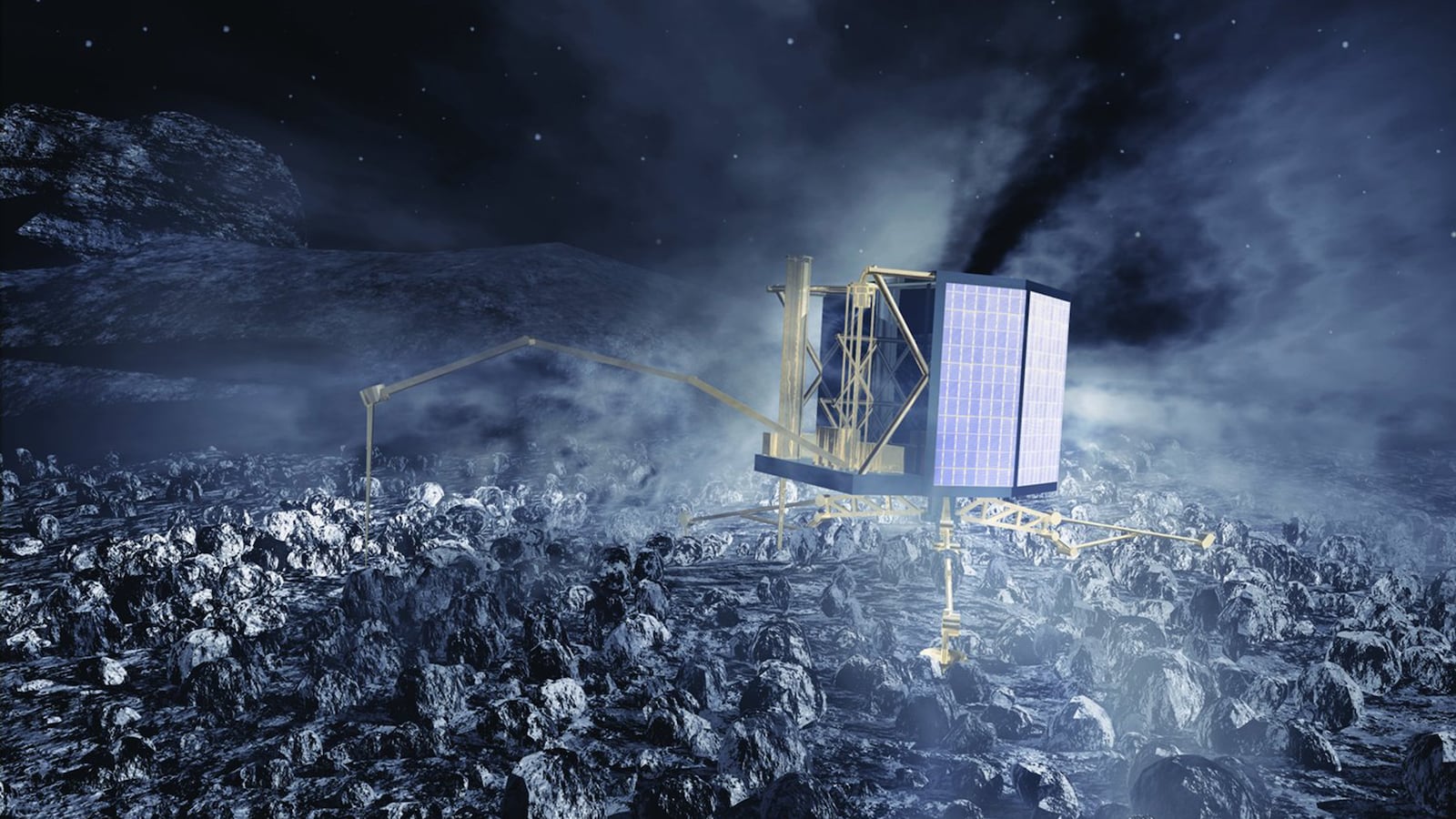

Philae—a spider-like lander the size of a washing machine—descended on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko back in November. Unable to latch onto the icy surface of the comet, Philae bounced into a dark area with no sunlight. The solar powered machine stayed alive for just a few short days.

This week, Philae moved from darkness into light, awake once more.

The resurrection of Philae means a great deal for the astronomical world—but perhaps even more for humankind. If the lander survives long enough to complete its mission, it may unlock the origin of life itself. Here is its story.

***

On March 2nd, 2004, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Rosetta space probe on an unprecedented, one-way mission to find answers. On its back, Rosetta carried Philae, the lander that would eventually enter the history books itself.

For years, the pair passed through the darkness of space—sometimes slumbering—with each day bringing them closer to their ultimate goal: a rendezvous with comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Rosetta’s mission is to study the comet as it drifts through the relatively cold darkness of space and then watch as the warm embrace of the Sun awakens the comet back to life, slowly melting its surface as the comet draws closer.

On August 6th 2014—ten years after the initial launch—the long dark night was over. Halfway between Mars and Jupiter, Rosetta and Philae reached their destination. Orbiting at a distance of only 200 kilometers from the cometary nucleus, Rosetta immediately went to work, sending back image after image to expectant scientists on Earth.

Thousands of photos revealed incredible landscapes of ice, dust, and dirt. Exposing dark spots and light, the images helped Rosetta pinpoint five potential landing sites for little Philae. Some three months later, on November 12th, Philae separated itself from Rosetta, never to return, and began its descent toward its chosen landing site, J. As it drew closer, it gathered data and faithfully transmitted its findings back home.

At first there was confusion; the data was not as expected. It was as though the lander was drawing closer to the comet but then moving away… something was clearly wrong. Philae hadn’t landed.

Unlike the Sun, comets have very little influence over anything that approaches them. No strong gravity to pull an object toward them; no fiery heat to melt the surface of any unsuspecting sacrifice. Only cold, dusty darkness illuminated by the light of the still distant Sun.

Philae was unable to grip onto the comet’s icy surface and come to a gentle stop. Instead, it bounced back up toward the emptiness of space—not just once, but twice. For two hours it narrowly escaped becoming lost completely. Eventually, it settled.

Now safely on the surface, but far from its intended target, Philae was drenched in darkness, hidden within the shadow of a nearby cliff or crater wall. Unaware of its fate, Philae faithfully continued its mission, but with no way to recharge its ailing battery, the lander lasted just a few days when, after transmitting all the data it could, it finally fell asleep.

Scientists zeroed in on the turning of the comet, which temporarily brought Philae back into sunlight again. Over time, the solar panels slowly drew more power until, from out of the darkness, a single 80-second transmission was received by Rosetta on June 13th.

Philae, having rested, was now ready to wake up and return to work.

Both Rosetta and Philae are designed to answer some of the mysteries surrounding comets; specifically, the nature of the nucleus and the composition of the comet itself.

Finding the answers can help scientists resolve some of the most fundamental questions of our time: who are we and where do we come from?

Comets, the great aunts and uncles of the planets, may hold the secrets of our solar system.

Born before the planets themselves, they still contain the same material as they did billions of years ago, when the Sun was still young. Like the rings in a tree, they can tell us a great deal about what the early solar system was like, long before the planets, and long before we were born.

They orbit the outer reaches of the solar system for an eternity, hundreds of millions of miles from the warmth of the Sun. After billions of years of wandering, like sleepwalkers, through the desperately cold darkness of space, they are pushed from their path by a passing star and begin the slow and involuntary fall toward the Sun.

Many comets will only make the journey once—tumbling toward our parent star until they plunge in to its fiery surface. Some will escape the Sun’s deathly grasp and, rejected, be flung out of the solar system, never to be seen again. For others, it’s a slow and gradual death, prolonged for thousands of years.

One comet, scientists believe, may have beaten the odds—and doing so, created life.

Instead of diving upon the Sun, it may have collided with the primordial and sterile Earth instead. Organic matter, once frozen within the icy dark depths of space, may have been freed and exposed to the warm light of the young Sun, even as the comet that carried it disintegrated and died. From darkness to light, death to life, the unassuming comet may be the progenitor of life on Earth.

It is for this reason that the Rosetta mission is such an important one, a potentially groundbreaking journey to discover the true identity of comets once and for allthe beginning of life itself.

At this point, Philae’s ultimate fate remains uncertain. Some ten months after its arrival, the comet is now within the orbit of Mars and continues on its course, headed toward its closest approach to the Sun on August 13th. With each passing mile, the surface will continue to warm and the frozen ice will slowly melt.

As the comet wastes away, so it will surrender its secrets.

Rosetta and Philae will continue to listen and relay all that they can. As the comet passes the Sun, it may become so active that it unintentionally throws Philae off the surface or causes its destruction. Its nucleus may fracture and the comet may split in two. Philae may somehow survive this cataclysm while Rosetta may lose its orbit and drift off into space.

Or their lives, like the comet itself, might end a little more slowly.

The comet, returning to the cold darkness of space, will settle down. With both Rosetta and Philae reliant upon solar power, the fading sunlight will eventually be too weak and both craft, like the comet itself, will eventually become cold and dark. In six and a half years, the comet will return.

This time, however, it may make the journey alone.