The two candidates for president share more than their Harvard Law degrees and their fiercely competitive instincts: both Barack Obama and Mitt Romney also convey an odd but undeniable sense of rootlessness, bearing connections to so many different corners of the country that they don’t seem to originate from any place in particular.

That disconnect from any organic, regional identity has undoubtedly contributed to the “birther” insanity, with dedicated crackpots supplementing their longstanding challenges to Obama’s status as a “natural born” citizen with new lawsuits claiming that Romney fails to qualify for the presidency due to his father’s Mexican birth. Unlike Bill Clinton, whose accent, personal history and long service as governor stamped him indelibly as a son of Arkansas, Romney and Obama seem cosmopolitan rather than homey, national (and even international) rather than local.

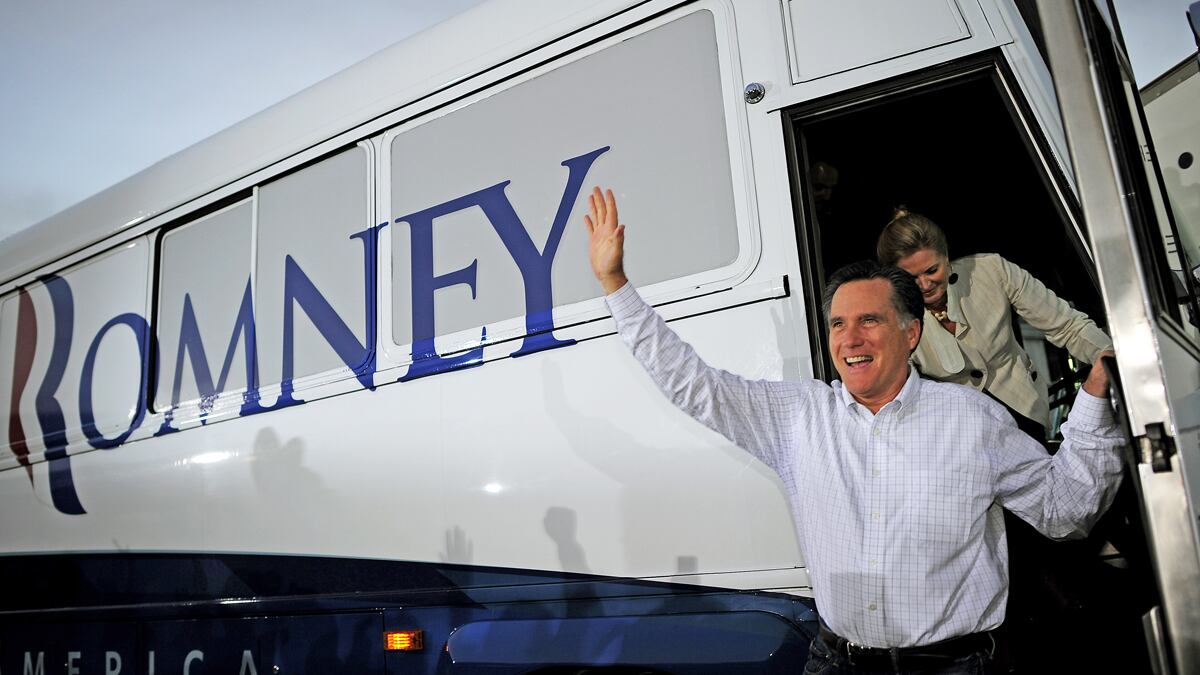

Romney won election as governor of Massachusetts, but he established other homes in New Hampshire and California, after growing up in Michigan. His father, George, served three terms as governor of the Wolverine State, but Mitt’s grandparents made their home in Mexico and lived there until George was a small boy. The Romneys also enjoy strong ties to Utah, where Mitt spent his undergraduate years at Brigham Young University and rescued the 2002 Winter Olympics.

Whatever his virtues as a candidate, Romney clearly lacks the distinctive New England flavor of the last Bay State candidate to win the presidency: John Fitzgerald Kennedy conveyed an unmistakable aura of Beantown authenticity, with his tangy accent, family heritage (his grandfather and namesake John Fitzgerald had been a beloved mayor of Boston), love of sailing, and elite regional schooling. By contrast, Romney may be derided by his GOP opponents as a “Massachusetts moderate” but he could actually hail from just about anywhere—though short-lived attempts to present himself as a grits-loving honorary Southerner didn’t work out too well in the Mississippi primary.

In the same sense, Barack Obama comes across as the man from everywhere and nowhere—representing his own exotic planet far more than he does the Southside Chicago district that actually elected him to the Illinois State Senate. The president’s erstwhile father lived his entire life in Kenya other than five brief student years in Hawaii and Massachusetts; his mother, born in Wichita, raised mostly in Seattle, lived the great bulk of her adult life in Indonesia. Her son endured an unstable childhood in Hawaii, Seattle (briefly), Indonesia and then Hawaii again, before pursuing his education in Los Angeles, New York City, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. His decision at age 24 to identify himself as a Chicagoan counted as career-driven and political—made without reference to family ties of any kind. Many observers have noted the president’s pronounced habit of reverting to the lilting, Southern-inflected cadences of traditional black preachers when he addresses predominantly African-American audiences, but it’s an odd affectation given that none of his black relatives (all of whom lived their lives in Africa, not the United States) ever spoke that way.

Critics of George W. Bush viewed his thick Texas twang as comparably calculated—part of a good ol’ boy pose meant to obscure his Connecticut birth and patrician, New England education at Andover, Yale, and Harvard. In fact, the Bush family dynasty that has played such a prominent role in recent politics lacks any single geographic base of operations. Prescott Bush, father of one president and the grandfather of another, grew up in Ohio but went on to represent Connecticut in the U.S. Senate. His son, George H.W. Bush, was born in Massachusetts but represented Texas in the House of Representatives; the next generation produced governors of both Texas and Florida. So which community, which state, would this influential and far-flung family view as the ancestral home? Actually, tribal reunions occur at a rambling manse in Kennebunkport, Maine.

In fairness, recent national leaders who lack clear connection to some deeply rooted point of origin reflect an age-old, honorable American pattern of moving from place to place in search of “elbow room” or fresh opportunities. We have always counted as restless people, arriving in this country from remote corners of the earth and setting up fresh settlements throughout a vast continent. Even today, we move into new homes at an average rate of once every seven years. Our national symbol may be the bald eagle but it might as well be the moving van—or, previously, the covered wagon.

No wonder local electorates regularly embrace newcomers and make them their own. Abraham Lincoln spent his boyhood years in Kentucky and Indiana but migrated to Illinois at age 21, forever stamping that state as “the Land of Lincoln.” Lincoln’s chief opponent in the epic presidential election of 1860 also emerged from the rough-and-tumble frontier politics of Illinois and ultimately represented his state in the U.S. Senate, but Stephen A. Douglas had grown up entirely in Vermont.

In the past, such famous transplants established deep roots in a new community before they presumed to put themselves forward as candidates for major elective offices. Today, however, ambitious politicians feel no compunction at launching initial campaigns as strangers and newcomers. Hillary Clinton offers the most extreme example: the Illinois native never even lived in New York before she persuaded Empire State voters that she counted as uniquely qualified to represent them in Washington.

There’s no crime in any of this, but there is a potent lesson: localism and regionalism play insignificant roles in contemporary politics. With more and more power flowing away from states and cities and to the federal government, with most Americans spending their time saturated in national media that erase or erode all provincial distinctions, it hardly matters whether a candidate counts as a homegrown hero who feels in his bones what makes a given part of the country unique and valuable. Chances are, the distinctive local culture has begun to wither and wilt anyway, so why should voters insist on homeboy candidates any more than fans demand that the sports teams that inspire such fierce civic pride must feature stars who grew up in the vicinity?

In contemplating his upcoming choice of a running mate, Romney should consider his own lack of local-boy credibility and dispense with conventional notions of geographical balance. Would Paul Ryan make for an unbalanced ticket because he’s from Wisconsin and Romney’s from Michigan, or would Chris Christie or Kelly Ayotte make for more inappropriate running mates because they’re both from the Northeast and Romney’s from Massachusetts?

Yes, we may have lost something compelling, nostalgic, even valuable with the eclipse of regional loyalty in American politics. But a clear-eyed consideration of this strange presidential race between two candidates from nowhere and everywhere strongly suggests that no candidate will gain by pretending it’s still there.