Our immune system has one function: to keep us safe. Comprised of various organs, cells, and proteins, it hums silently in the background of our bodies, protecting us from rogue bacteria, viruses, fungi, and toxins. If one of those bad actors appears, the immune system sends cells to surround, attack, and neutralize. Easy.

But sometimes that sophisticated system malfunctions; it senses danger where there isn’t any, and sends its henchmen out of turn. It’s the hypervigilant subway rider with a clenched fist inside his coat pocket, ready for a potential mugging. For those who have autoimmune diseases, the immune system pulls out that fist and punches at targets that have done nothing wrong.

That’s where immunosuppressant drugs like hydroxychloroquine—which I take daily for the autoimmune disease lupus—come in. (Many lupus patients faced scarcity problems with the drug after it was falsely claimed by some to cure COVID.) Hydroxychloroquine tamps down an overactive system, providing a chemical version of: shhh, you’re OK. No need for punching. Unfortunately, these types of drugs must quiet the entire immune system, which leaves people with little or no defense against illnesses, infections, or viruses like COVID-19.

Because of my immunocompromised status, I was among the earliest eligible for the vaccines, and then to qualify for my third Pfizer shot. That’s why I was so surprised last month when I got COVID.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been. Though there are at least 7 million immunocompromised people in the U.S., we weren’t included in the vaccine trials. No one knew how effective the vaccines would be for us—or if they would be at all.

With that unknown hanging in the air, and well before the third shots were made available, Rochelle Walensky, the head of the CDC, announced in May 2021 that anyone who was fully vaccinated “could participate in indoor and outdoor activities—large or small—without wearing a mask or physically distancing.” Her statement concerned me, as it seemed premature.

Though immunocompromised people make up just 3 percent of the population, a recent study found that 44 percent of hospitalized breakthrough cases are immunocompromised people.

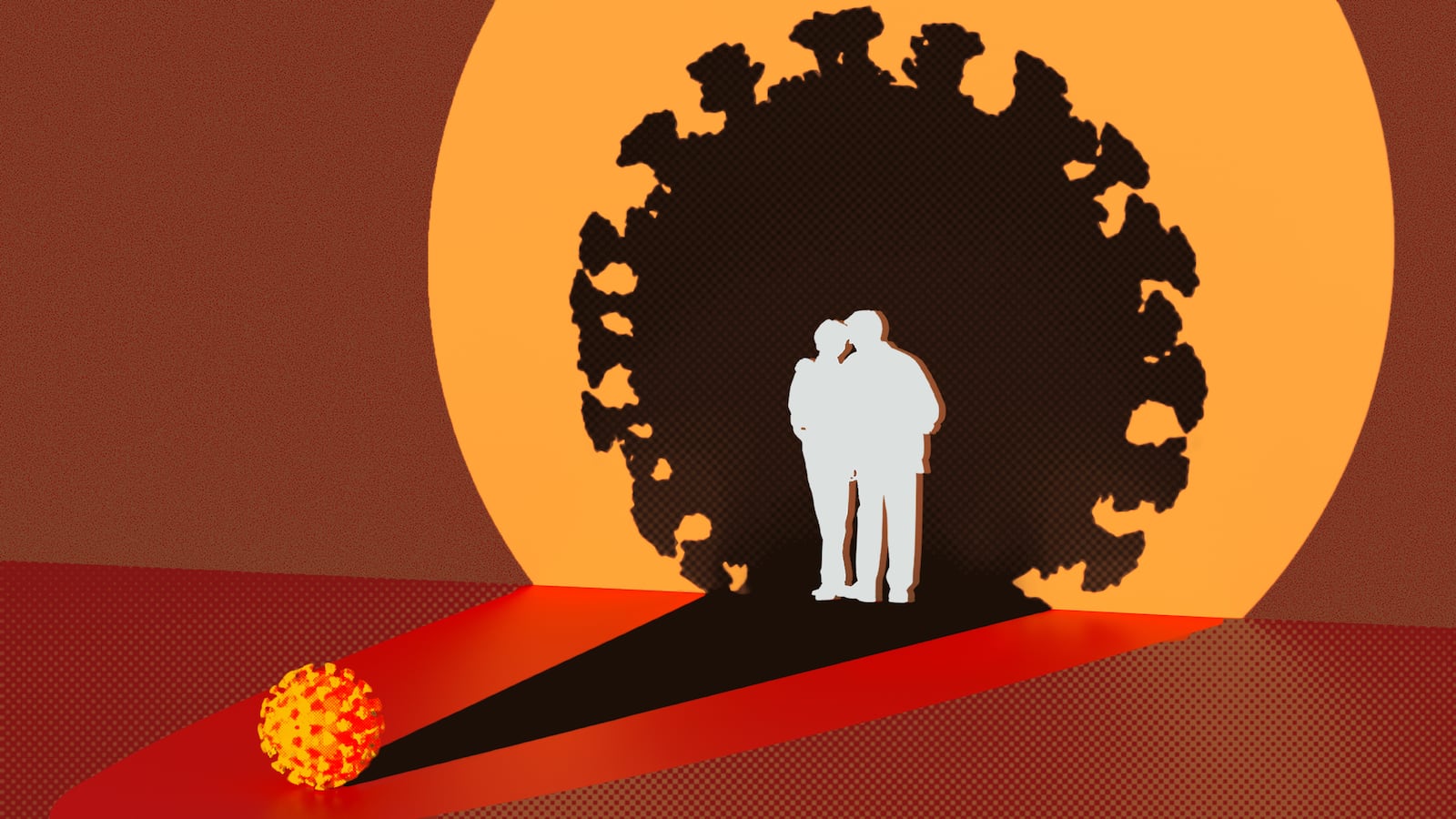

Still, I wanted to be optimistic, especially after my third shot. Once the positivity rate in my city declined, I went to gatherings in backyards, and even planned a short trip to the city I’d left at the start of the pandemic. Every place my boyfriend and I went during the trip required proof of vaccination. I felt safe.

Two days after we returned home, my boyfriend (who is also immunocompromised) said he felt like he was coming down with something. The next day he was worse. “I think maybe I should get a COVID test,” he said.

I hadn’t wanted to acknowledge it, but my entire body ached, yet also felt strangely buzzy. My throat hurt. This was different than a lupus flare.

Thirty-six hours later, my test came back positive. My boyfriend’s did, too.

We were fortunate to qualify for monoclonal antibody treatment at a clinic two hours away. Still, over the next few weeks, we were couch-bound and deeply uncomfortable. If we hadn’t been vaccinated at all, I’m certain our outcomes would have been much worse.

A new guideline from the CDC, updated in August 2021, reads: “People who have a condition or are taking medications that weaken their immune system may not be fully protected even if they are fully vaccinated. They should continue to take all precautions recommended for unvaccinated people.”

Once again normalcy seems a long way off. Will I ever be able to safely teach in a classroom again? What about a concert? A movie? Seven million of us remain in limbo, still right in the middle of the pandemic. Watching from a socially appropriate distance as most everyone else, according to the CDC, can resume many aspects of their normal lives. That said, COVID cases are surging in many parts of the country. Especially with winter coming, even those with no preconditions may soon have to back off from some of the pre-pandemic activities they’d been able to resume.

Which is even more reason that it’s crucial to get more people vaccinated. As of Nov. 16, only 59 percent of Americans had been fully vaccinated (68 percent had had one shot). I’ve heard one argument, repeatedly, against it: I’m healthy and my immune system will protect me. That’s wonderful; I’m happy for you (and, let’s be honest, envious). But many perfectly healthy people have died from this virus: 30-year-old bodybuilders, 10-year-old kids. You cannot know for certain that your unvaccinated immune system will protect you.

But you can be sure of one thing: Your healthy immune system won’t protect anyone else. Right now, community responsibility should take priority. Because if not, we all lose. Consider this a plea from me, one of 7 million. You may not know me personally, but I guarantee you know one of us.