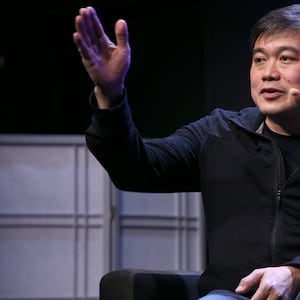

Harvard biologist George Church already had to apologize for palling around with Jeffrey Epstein even after the financier pleaded to guilty to preying on minors a decade ago. Now he’s raising eyebrows again—with plans for a genetics-based dating app.

In an interview with 60 Minutes, Church said his technology would pair people based on the propensity of their genes, when combined in children, to eliminate hereditary diseases.

“That sounds like eugenics,” Fordham adjunct ethics professor and science journalist Elizabeth Yuko, who studies bioethics, told The Daily Beast on Monday. (The tech and science news site Gizmodo called Church’s idea “an app only a eugenicist could love.”)

Yuko compared the app, as described, to the Nazi goal of cultivating a master race: “I thought we realized after World War II that we weren’t going to be doing that,” she said.

Church was part of the coterie of scientists with whom Epstein ingratiated himself via large donations, and Epstein helped bankroll his lab from 2005 to 2007. Church has admitted he repeatedly met and spoke with Epstein for years after the 2008 plea deal that landed him on the sex-offender registry.

Epstein had a twisted take on genetics, hosting scientific conferences at which he expressed his desire to propagate his own genome by impregnating up to 20 women at a time at his New Mexico ranch, like cattle stock.

In the 60 Minutes interview, Church called his ties to Epstein “unfortunate” and added: “You don't always know your donors as well as you would like.”

But much of the segment was devoted to Church’s genetic-engineering work at Harvard Medical School, including the app that would theoretically screen out potential mates with the “wrong” DNA.

“You wouldn’t find out who you’re not compatible with. You’ll just find out who you are compatible with,” Church said.

“You’re suggesting that if everyone has their genome sequenced and the correct matches are made, that all of these diseases could be eliminated?” 60 Minutes’ Scott Pelley asked.

“Right. It’s 7,000 diseases. It’s about 5% of the population. It’s about a trillion dollars a year, worldwide,” Church said.

The geneticist didn’t drop the app’s name (“Punnett Square,” anyone?) or how far along it is in development. He also didn’t respond to a request for comment.

In the interview, Church acknowledged the drawbacks of genetic sorting. He suffers from dyslexia, attention deficit disorder, and narcolepsy—disorders that might render him an incompatible match to many.

“If somebody had sequenced your genome some years ago, you might not have made the grade in some way,” Pelley said.

“I mean, that’s true,” Church replied. “I would hope that society sees the benefit of diversity, not just ancestral diversity, but in our abilities. There’s no perfect person.”

Yuko said the selection criteria would be a sticking point for Church’s app idea.

“It’s not clear what conditions or diseases will be screened for. Who makes that list? What’s undesirable?” she said. “That’s classifying people into acceptable humans and others.”