One hot afternoon during the summer of 1890 a pod of theatrical types washed up against the bar at New York’s Ashland House hotel. That in itself was normal enough: the Ashland was across from the fashionable Lyceum Theatre (then located on Fourth Avenue and 24th Street) and, although somewhat antiquated, it still maintained a bar that was among the city’s best. (Theater folk were known for their discernment in such matters.) And since—with air conditioning a thing of the future—New York theaters were dark in the summer, there was nothing to keep those actors who were successful enough to escape doing summer stock from spending their afternoons sitting around café tables shooting the shit.

What wasn’t normal was who was in this group: along with three or four promising younger actors (all unremembered by posterity) there were some real luminaries, including Dion Boucicault, the prolific Irish-American actor and playwright of the 1850s and 1860s, then only weeks from his death, and Maurice Barrymore, founder of the Barrymore dynasty and perhaps the leading actor in the country.

It was a third man, however, who made the greatest impression that day on Patrick Gavin Duffy, the hotel’s young Irish-born head bartender, who had never seen him before. After Duffy showed the group to a couple of tables and inquired as to what they would have—we must presume the standard summer drinks of the day: Mint Juleps, Sherry Cobblers, perhaps the newly-fashionable Rickey and even the Broadway swell’s latest Anglophile affectation, Scotch whisky and soda—they got to talking, and eventually the conversation turned to Ireland, her people and her politics. That’s when the stranger finally put his oar in.

“There was something in his appearance, height, walk and manner which I thought Napoleonic,” recalled Duffy, and “under the pretense of drying glasses, waiting to render service, and doing other little jobs,” he kept within hearing distance as for the next hour or so the man calmly laid out the long, cruel history of England’s domination of the Emerald Isle in language that, while “unaffected and unexaggerated,” carried a “power and persuasion” that held his audience spellbound. When he finished, Barrymore, English to the core—he was an Oxford man and had been middleweight boxing champion of England—jumped up and exclaimed, “you electrify me! Damn those English rulers—they had no hearts!”

That stranger was James O’Neill, father of Eugene, then 45 years old and at the height of his success as an actor. While James drank, and sometimes heavily, according to those who knew him he was anything but the specimen of a miserly, desperate alcoholic his son portrayed in his harrowing play Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Rather, James O’Neill’s drinking followed the pattern then common among actors, writers, gamblers, politicians and other members of the so-called “Sporting Fraternity”: it was, as on that afternoon in 1890, social, convivial and performative. To be sure, some days he would put away a quart of whiskey, but it was always in company, and it never caused him to miss a performance, although he might have wobbled his way through the occasional one.

In fact, it was drinkers like James O’Neill around whom the high tradition of the American bar was originally built: men who knew their drinks, who could hold their liquor (with no more than the occasional slip-up), who stood their rounds and paid their tabs without bitching about the price. If such men were also eloquent and accomplished, so much the better—as long as those qualities were accompanied by good humor and a disinclination to grip a dollar so tightly that it can’t wriggle free. If that liberality led to a sport being temporarily embarrassed, that was never held against him, provided that his need was not too obvious or too prolonged. If it was, well, he could do his drinking elsewhere.

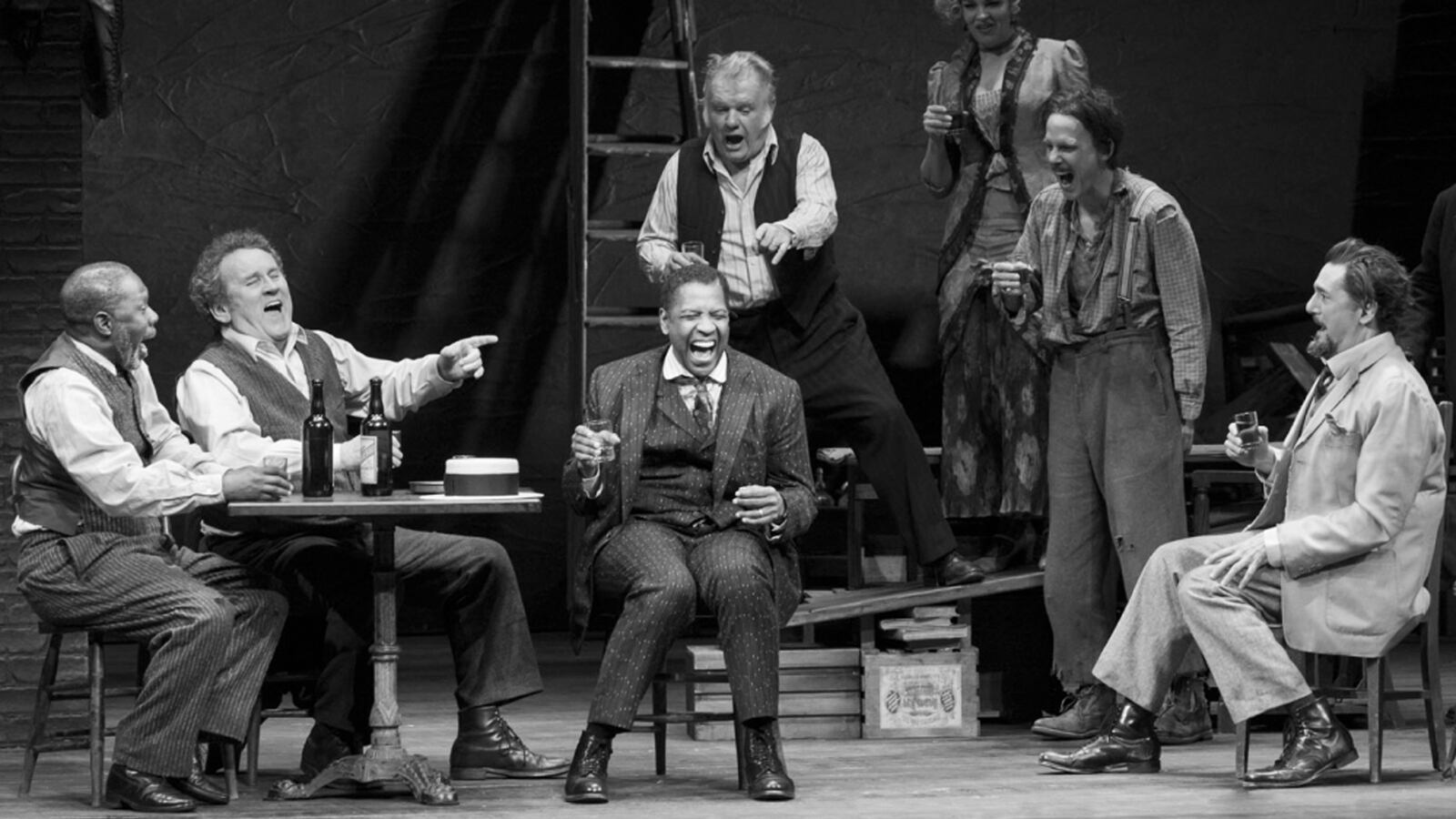

Like, say, at a place along the lines of Harry Hope’s, the bar conjured up by James O’Neill’s son Eugene for his 1939 masterwork, The Iceman Cometh, recently revived to great effect on Broadway with Denzel Washington. Harry Hope’s is not a happy place, and the lost crew of alcoholic losers who populate it in the summer of 1912, when the play is set, are as lacking in eloquence and accomplishment as they are in money or prospects of getting any.

O’Neill’s portrayal of Harry Hope’s as the “No Chance Saloon…The End of the Line Café,” to cite one character’s description of it, might be laden with DHM, as we used to call it in Doc Williams’ eleventh-grade English class—“Deep Hidden Meaning.” But it is not impressionistic: his description of the bar is precise and detailed. When he identifies the bar as a “Raines-Law hotel,” he explains exactly what that is. (The 1896 New York law of that name that stipulated that the only establishments allowed to serve alcohol on Sundays and after hours were hotel restaurants, to which the more clever and unscrupulous of the city’s saloonkeepers responded by renting out hastily-appointed rooms upstairs and turning their back rooms into restaurants by, as O’Neill puts it in his introduction, “putting a property sandwich in the middle of each table, an old desiccated ruin of dust-laden bread and mummified ham or cheese which only the drunkest yokel from the sticks ever regarded as anything but a noisome table decoration.”)

Everything about Harry Hope’s is correct for a bar of its type, from the fly netting over the mirror; to the “turrible [sic] bug juice” kept in casks behind the bar and passed off as whiskey at five cents a “ball,” or shot; to the way that bug-juice is served, where the customer is handed the bottle, a shot glass and a glass of water as chaser and expected to pour the whiskey (or, more accurately, “whiskey”) himself; to the small cigar Rocky Pioggia, the night bartender, takes instead when a patron offers to buy him a ball of his own. Joe Mott, the bar’s “porter,” or combination janitor-barback, is black, as was common at the time (in most Northern cities it was in fact the only job in a bar with a white clientele open to a black man). There are three hookers working out of the bar—the Raines Law was notorious for increasing prostitution in the city, what with all the cheap rooms suddenly available in the cheap “hotels.” The D.T.s resultant from constantly drinking the bar’s booze are identified as having “the Brooklyn boys” coming after one, a piece of sporting-life slang that did not survive Prohibition and has yet to be adequately explained.

O’Neill based Harry Hope’s on three of his New York haunts back in the 1910s: Jimmy’s Hotel and Café, aka “Jimmy’s Place” or “Jimmy the Priest’s,” at 252 Fulton Street, where the World Trade Center tower stands now; the Golden Swan, in the shadow of the elevated tracks at 6th Ave. and West 4th Street on a spot now occupied by the Golden Swan Garden, and the bar of the Garden Hotel, at 63 Madison Ave. on the northeast corner of 27th Street.

Jimmy’s, “a dirty, evil-smelling, drear-looking dive,” as the New York World dubbed it in 1919, inspired the physical setting and some of the characters. It was not, however, strictly a Raines-Law joint, having been a legitimate, if undistinguished hotel since 1850, give or take a year or two (its slow slide into disreputability began in the 1870s and accelerated rapidly around the turn of the century when its residents began turning up in police reports). What’s more, Jimmy—James Condon, a New York-born Irishman whose nickname was due to his white hair and benign expression—actually fed his lodgers, up to a point, serving them a daily bowl of soup. On the other hand, “bug juice” was probably too good a term for his whiskey: in 1919, he and his bartender, Billy Nolan, were arrested after four of his lodgers died from methanol poisoning. Thus, ended Jimmy’s.

From the Golden Swan came a number of O’Neill’s characters in the play, including Joe Mott, the black porter (based on the Golden Swan regular Joe Smith), the working girls and Harry Hope himself. Another old establishment, indeed one of the oldest in the city, the Golden Swan was run by Tom Wallace from the mid 1870s until his death in 1922. By the time O’Neill encountered him, he was a cantankerous, half-blind old ward-heeler who was prone to sitting around the bar getting contentiously drunk with his decrepit cronies, all characteristics appropriated by the playwright for Hope. Wallace still had enough political pull to keep the establishment off the police list of “disorderly houses,” despite it being a favored resort of the Hudson Dusters, a notorious local gang, and the back room—nicknamed the “Hell Hole”—being a haven for streetwalkers.

Yet the Golden Swan was not all that bleak, not by New York standards. There was a reasonable free lunch in front and the Hell Hole attracted many of Greenwich Village’s Bohemians. Artists, writers and actors were a common sight there, including John Sloan, dean of the “Ashcan School” of American painting and fellow-painter Charles Demuth, writer-agitator Dorothy Day and Agnes Boulton, another writer who would become O’Neill’s second wife. There they were able to rub shoulders with the rougher element without being entirely submerged in it.

The Garden Hotel, a theatrical hotel a couple of cuts below the Ashland House that was open from 1888 until 1919, contributed a few more of the play’s characters and incidents. Yet while it may have been on the seedy side, it was not particularly bleak—not compared to Jimmy the Priest’s, and definitely not compared to a truly desperate dive like the notorious McGurk’s Suicide Hall on the Bowery. O’Neill considered Louie, the hotel’s bartender, a particularly good friend, probably due in considerable part to the fact that in the summer of 1916, when the playwright’s alcoholism had reached its peak and his fortunes their nadir, he was still willing to extend him credit for a drink or three even when Condon and Wallace had turned off the spigot. (The fact that James O’Neill had been a frequent guest at the hotel and still dropped in might have had something to do with Louie’s generosity, or it could just be that, as O’Neill later used to say, “bartenders are the most sympathetic people in the world”).

That summer, the 28-year-old O’Neill was squatting in a loft downtown not far from Jimmy’s. To get his needed morning eye-opener at the Garden, he’d have to take the Subway or, even worse, walk all the way up to 27th Street. Then, as Arthur and Barbara Gelb describe it in their massive O’Neill biography, O’Neil: Life with Monte Cristo:

“Trembling from the effort of his hike, O’Neill would prop himself against the bar and order his shot. The bartender…would place a shot glass in front of him, toss a towel across the bar, as though absentmindedly forgetting it, and move away. Arranging the towel around his neck, O’Neill would grasp both the glass of whiskey and an end of the towel in one hand and clutch the other end of the towel with his other hand. Using the towel as a pulley, he would laboriously hoist the glass to his lips. His hands trembled so violently that even with this aid he was barely able to pour the whiskey down his throat, and often spilled part of it.”

Fortunately for him, and for American letters, in 1916 O’Neill’s plays started catching on and he found a way to do something other than drink. But even then, and indeed for the rest of his career, he didn’t put these three bars behind him, but wove them into his work. It’s not just The Iceman Cometh: Anna Christie, The Hairy Ape and The Emperor Jones all draw on them, as do many of his other plays. Nor did he hide the source of his material—in fact, in the 1920s and 1930s, in interview after interview, he waved Jimmy’s, the Golden Swan and the Garden in the public’s face.

In 1924, O’Neill was telling the New York Times Magazine that “Jimmy the Priest’s certainly was a hell hole” before going on to explain exactly how. In 1928, it was the New York Sun and the story of the broken-down circus men and such who frequented the Garden bar (“a good place”). The Golden Swan, a known literary haunt, got fewer words, but eventually that found its way into his dive-bar litany. In 1936, when O’Neill won the Nobel Prize, the New York Post named them as his “three favorite haunts” of years past, presenting them as a trey of bricks in the foundation of his biography, “each of which marks a period in his life.”

Nowadays, we’re used to our celebrated artists positioning themselves as horny-handed sons of toil; as unpretentious regular Joes and Janes who would rather knock back Miller High Life shorties and shots of Fireball with the regular folk than drink Taittinger at the Grand Tier Café between acts of La Traviata. Back in the 1920s, though, that was something new. Previous generations of artists aspired to—well, that afternoon at the Ashland House. Elegant company, witty and accomplished, drinking fine drinks and treating themselves well. Poverty and rough company were what you escaped from and were your penalties for failure.

James O’Neill might have drunk, from time to time, at the Garden bar, but he much preferred the genteel English Taproom at the St. George Hotel, down the block. He also might conceivably have found himself in the Hell Hole once or twice, if led there by the company he was with, but he would have never been a regular. If he had to so much as set foot in Jimmy the Priest’s, it would have been a confession of defeat in life.

For Eugene, though, these bars were his ancestor portraits, his bloody shirt, his carved fertility gods. They were the documentation for his searing message. They authenticized him. Unfortunately, for them to do their work, he had to deauthenticize them.

In 1932, O’Neill talked to the Daily News about the “sailors, on shore leave or stranded; longshoremen, waterfront riffraff, gangsters, down and outers, [and] drifters from the ends of the earth” that he rubbed shoulders with at Jimmy’s. “They were sincere, loyal and generous,” he added, and it was from them that he learned “not to sit in judgment on people”—that is, other than himself. “If a person is to learn the meaning of life,” he added, “he must learn to like the facts about himself—ugly as they may seem to his sentimental vanity—before he can lay hold to the truth behind the facts, and the truth is never ugly.”

In The Iceman Cometh, Harry Hope’s is essentially a giant machine for showing its denizens the facts about themselves. It is an earnest place, a serious place. Sure, there are flashes of grim humor, but they are nothing but paradiddles in the drumbeat of self-revelation that makes up the play.

I wonder, however, if the nights at Jimmy the Priest’s were anything at all like the ones at Harry Hope’s. In 1936 and 1939, Joseph Mitchell, another great American writer who had his issues with alcohol, wrote a couple of articles for the New Yorker about another bar, one just a block or two from Jimmy’s (“Bar & Grill,” November 21, 1936; “Obituary of a Gin Mill,” January 7, 1939). It is not a fancy place: the neon sign is “twitchy,” the bar “sags here and there” and “on damp days the place smells like a stable.” Like Harry Hope’s, it, too “also functions as a bank, as a sanitarium, as a gymnasium, and sometimes as a home.”

Nick’s Greenwich Tavern (Mitchell called it “Dick’s”) was run by Dominic “Nick Martini” Setteducati, a stout, grumpy Italian immigrant who was also known as “the House,” for his ability to beat the customers at bar dice. Setteducati had opened the place as a speakeasy and then turned it into a legal bar when Repeal came, or at least legal-ish. It was not a dull bar. The clientele, a fully O’Neillian mixture of various strands of riffraff—although with fewer sailors and more reporters (before the invention of journalism school, a fully working-class job) and superannuated, rooming house-dwelling office clerks—found ways of amusing themselves while waiting for someone to buy them a drink that didn’t involve introspection and self-examination or the haunted avoidance thereof.

Take a character known as “Jeeter Lester,” a Southerner. “Jeeter is an expert,” wrote Mitchell in 1936, “at snapping a coin, hidden between his fingers, against a highball glass the moment it touches his lips, making a noise as if he had bit a piece out of the glass. Then he screams and spits out a mouthful of ice, which looks a great deal like glass when it is flying through the air.” This startled the newcomers and amused the regulars. Then there was the crew of old rummies who, when the spirit moved them, would crouch against the bar, nudging it with their shoulders, and sing the “Song of the Volga Boatmen,” or the quartet of Federal inspectors of something or other who would, when one of their number got a call from work, crowd around the telephone booth, banging on it in rhythm and yelling “listen to the tom tom in the jungle.” Etcetera. Mitchell goes on for pages with this stuff.

Having spent considerable time in dive bars myself over the last four decades, I suspect Mitchell’s accounts of Nick’s (along with those of H. Allen Smith and the other writers who chronicled its doings) are far closer to what went on at O’Neill’s three bars than the doings exposed in The Iceman Cometh. Sure, some end-of-the-line dives with long-established corps of regulars are morose, but in my experience most have a thick vein of fuck-the-world amusement running through them. If a character like Theodore “Hickey” Hickman, the demonic traveling salesman who is determined to get the battered hulks at Harry Hope’s to free themselves from their miserable illusions and face who they really are, tried to peddle that guff at Nick’s—or, for that matter, at Hank’s, in Brooklyn, the Park Inn, in Manhattan, or Palmer’s, in Minneapolis, to name three iconic dives from my own past—he’d wouldn’t last 20 minutes before someone coldcocked him. (If he was at Nick’s, they would have stripped off his clothes, as they did with anyone who was unconscious, replaced them with whatever rags they found in the broom closet, filled his pockets with cryptic and threatening notes and dumped him in a doorway around the corner.) The point is, people who drink in such places tend to know who they are without any help from the Hickeys of this world.

When it comes to learning about life, I can’t imagine that young Patrick Gavin Duffy didn’t learn as much about it from the swells at the Ashland House as young Eugene O’Neill did from the bums at Jimmy the Priest’s. I’d like to see a play about that.