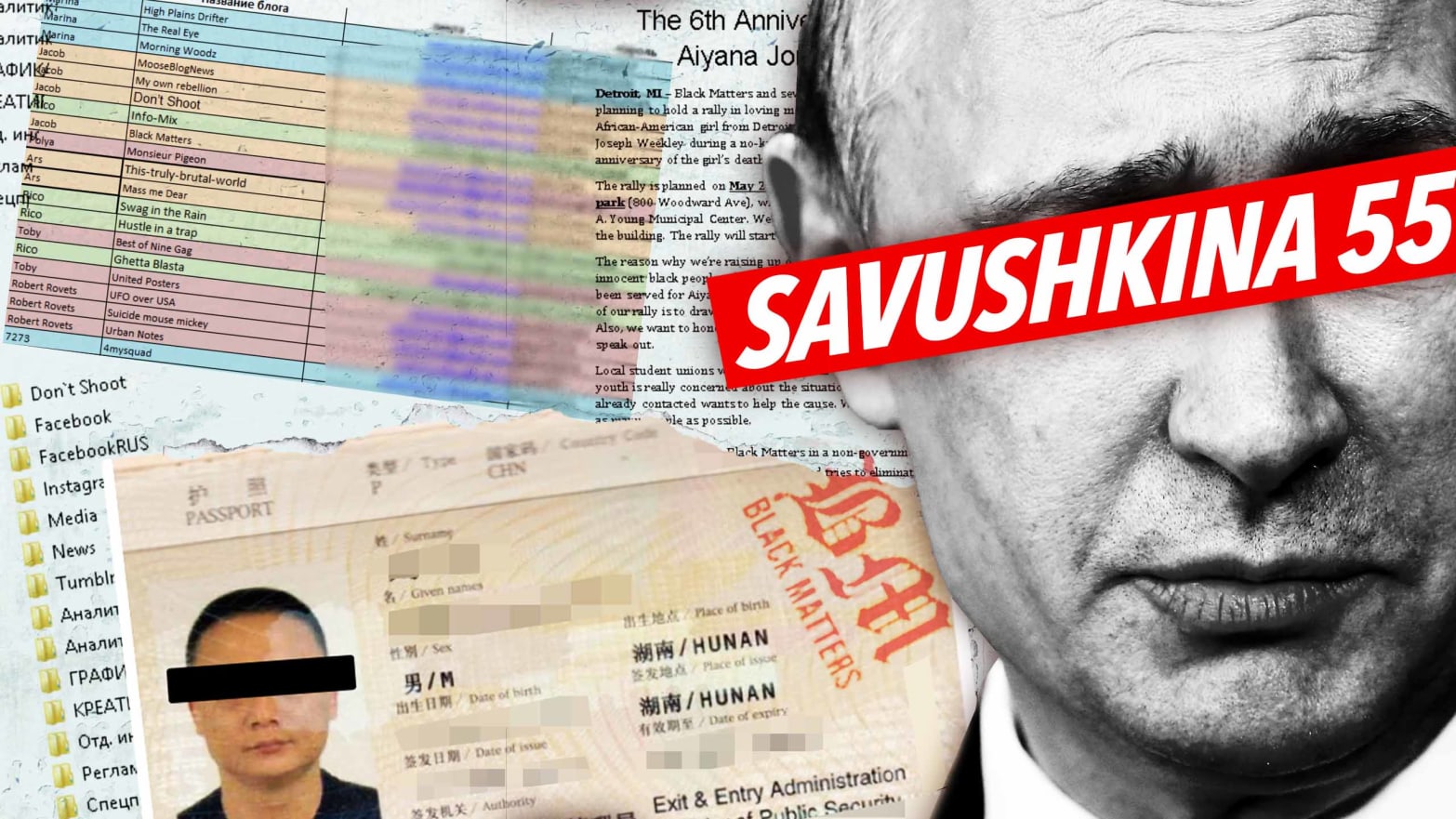

The Kremlin-backed troll farm at the center of Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. election has quietly suffered a catastrophic security breach, The Daily Beast has confirmed, in a leak that spilled new details of its operations onto obscure corners of the internet.

The Russian “information exchange” Joker.Buzz, which auctions off often stolen or confidential information, advertised a leak for a large cache of the Internet Research Agency’s (IRA) internal documents. It includes: names of Americans, activists in particular, whom the organization specifically targeted; American-based proxies used to access Reddit and the viral meme site 9Gag; and login information for troll farm accounts.

Even the advertisement for the document dump provides a trove of previously unknown information about the breadth of Russia’s disinformation effort in the United States, including rallies pushed by IRA social media accounts that turned violent.

While special counsel Robert Mueller’s recent conspiracy indictment against the IRA showed a sophisticated organization aimed at targeting U.S. voters with disinformation, the seller appears not to have understood the implications of the auction.

The listing was titled “Savushkina 55,” the physical address in St. Petersburg from which the troll farm used to operate. The date on the auction is listed as Feb. 10, 2017—seven months before Facebook and Twitter identified and pulled down Internet Research Agency accounts from Twitter. It received no bids. The seller, “AlexDA,” has not posted any other listings, and was unable to be reached. In Russian, the listing promised “working data from the department focused on the United States.”

While the date of the auction could not be independently confirmed, the authenticity of the leak can. The leaked documents list screen names connected to a number of American citizens who were used as unwitting proxies by the Russians. The Daily Beast was able to track down four of those citizens, whose names have not been previously revealed. The leak contains precise dates in 2016 in which the IRA-created account Blacktivist reached out to those U.S. citizens, plus a short description of the conversations. The Daily Beast spoke to those citizens, and confirmed they interacted with the Blacktivist account in the ways described by the IRA in the document. In one case, the American even provided screenshots of his interactions with the Russian troll trying to dupe him.

In short, the leaked document contains details of the Russian disinformation campaign that have not been previously made public—details which The Daily Beast was able to confirm.

The leak shows that even as the Russian trolls were able to influence and manipulate American political discourse online, they were less equipped to keep their own secrets. While The Daily Beast does not possess anything close to a comprehensive trove of the IRA’s internal operations, it is now likely that substantial amounts of the troll farm’s files are waiting to be discovered online.

But what The Daily Beast has seen provides a new level of texture and detail to the IRA’s U.S. efforts, online and off. While the troll farm’s use of YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook is now well-known, the leak shows that the Internet Research Agency also operated on Reddit and had a substantial footprint on Tumblr. They documented and tracked their personalized interactions with specific, unsuspecting Americans, some of whom are named in the leaks.

Those outreach efforts display conceptual sophistication. The leaks show that IRA impostor accounts targeted activists for specific causes the Russians wanted promoted. On the target list: the daughter of one of Martin Luther King’s lieutenants.

But the leaks also provide a glimpse into the troll farm’s weaknesses. Some of the Americans the group contacted described receiving impersonal entreaties from unfamiliar accounts, asking for trivial aid and then declining to follow up. The Internet Research Agency might have known how to leverage social media, but they knew far less about how users authentically interact with each other on it—which itself attracted suspicion amongst the very people the Russians were contacting.

“I couldn’t put my finger on it. I didn’t know who they were and why they were remaining anonymous, and I didn’t really see the need for it,” said Craig Carson, a Rochester, New York, attorney and civil rights activist who was contacted by the farm-created account Blacktivist.

Shanall LaRay Logan—who lives in Sacramento, California, and said she is active in Black Lives Matter campaigns —told The Daily Beast that these kind of trolling overtures are “actually just counterproductive to our movement.”

The leaks also reveal the IRA’s previously unreported connection to two additional 2016 rallies, one outside Atlanta and another in western New York, The Daily Beast can now confirm. One of them turned violent.

On Feb. 16, Mueller indicted 13 people for their involvement in the Russian troll farm. The allegations have yet to be proven in court—and may never be, given the unlikelihood of Russia arresting and extraditing them for trial. But, combined with the leaked IRA documents, they provide a glimpse into the organization’s tradecraft.

Mueller describes an extensive operation, both online and off, beginning in 2014, to “sow discord in the U.S. political system.” What the Internet Research Agency called its “Translator Project” involved over 80 employees and a monthly budget that stretched to over $1.25 million. As U.S. elections approached, its internal understanding of its goal was to engender American “distrust towards the candidates and the political system in general.” By February 2016, with the U.S. presidential election looming, it emphasized attacking Hillary Clinton, both from the right and the left simultaneously.

Its means included physical reconnaissance. Two IRA employees went on a road trip to visit nine American states stretching from New York to California “to gather intelligence” in June 2014. Five months later, a colleague spent another four days in Atlanta.

One of the employees who visited America was Anna Vladislavovna Bogacheva, then the head of the troll farm’s Department of Analytics. The auction of the leaked IRA data offers a glimpse into that department’s work, which appears focused on understanding America and teasing out the most contentious issues. One department folder is titled “US Migration Policy,” which would prove a cornerstone of the IRA’s most divisive trolling. Other folders cover “The ruling political oligarch,” “False promises of America,” and “Air strike costs”—likely a reference to Trump’s bombing of a Syrian military airfield, which Putin condemned and the IRA attacked as a waste of taxpayer money. One folder simply reads “Obama.”

After completing its recon, a key tactic of the troll farm was to present its offerings as authentically American. They stole actual Americans’ identities and established false cover identities online. A consistent approach was to posture as supporters of passionate causes. But those causes varied wildly across the political spectrum. Some Internet Research Agency-created accounts pretended to be Muslim groups, others anti-Muslim activists. They were advocates of black liberation on one hand and its most fervent American critics on the other—whatever was necessary to aggravate long-standing and very real American divisions.

Social media—particularly YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—magnified the troll farm’s reach. The money flowing into the Internet Research Agency’s coffers paid for a graphics department, data analytics, and other tools to improve their product, and they tailored their English-language propaganda to show up prominently in Google searches. One employee bragged: “I created all these pictures and posts, and the Americans believed that it was written by their people.”

But spreading misinformation on social media wasn’t enough. By summer 2016, the Internet Research Agency wanted to prompt Americans into the streets. Using tools like Facebook’s events page, they staged and promoted rallies for Donald Trump and against Clinton.

Just as social media permitted the IRA to scale a message up to reach millions, the same tools permitted person-to-person interaction to ensnare unwitting proxies. The troll farm’s employees, posturing as Americans, would “send individualized messages to real U.S. persons to request that they participate in and help organize” such rallies. Sometimes they had specific requests for unsuspecting activists: build a cage on a flatbed truck, or wear a costume to play-act Clinton heading to jail. For a June 23, 2016 rally, they solicited an American to recruit attendees to a pro-Trump rally with the promise of “giv[ing] you money to print posters and get a megaphone.”

The material leaked from the troll farm sheds additional light onto both the scope and the granularity of the tactics employed. In some cases, the efforts helped stoke clashes that turned violent. In others, they amounted to little but the occasional Facebook message to activists who were going to turn out for issue-based protests anyway. Flush with cash, the Internet Research Agency could afford to spread its bets.

The Russians chose their potential American targets carefully. As they sought to promote conflict at a rally in Stone Mountain, Georgia, the leaks indicate the Internet Research Agency reached out to a woman whose legacy hearkens back to the heart of the civil rights movement.

At a young age, in 1966, Barbara Williams Emerson protested the harassment of black students in Grenada, Mississippi, and was arrested for her efforts. She was following in the footsteps of her parents—one of whom is Hosea Williams, a key Martin Luther King Jr. lieutenant in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

After earning a Purple Heart as part of Gen George Patton’s (segregated) army, Hosea Williams endured a vicious beating for drinking out of a whites-only water fountain in his native Georgia. He would later organize voter-registration drives in the Deep South during the pivotal Freedom Summer of 1964 and march across the Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday. He took his fight to the Georgia Senate and the Atlanta City Council. While serving on the council in 1987, Williams, then 61 years old, confronted the Klan during a march through a segregated Forsyth County town. At that march, The New York Times reported at the time, a mob of “hundreds if not thousands” of rabid whites, David Duke among them, shouted “N---er, go home!” Today a road in Atlanta bears his name.

Williams’ daughter Emerson, now an academic and activist, told The Daily Beast she was familiar with the Blacktivist impostor account, but marginally so. Their posts started showing up in her feed, and she remembered Liking an article on its now-shuttered Facebook page, but “I don’t think I was contacted directly,” she said, and definitely not with any offer of money or resources. Despite whatever inroads Blacktivist might have sought to make with her, Emerson, who lives near Stone Mountain, didn’t even attend the protest that Blacktivist hyped.

“I remember thinking that whole Stone Mountain monuments thing… the removal of Confederate images was an example of a distraction of energy and action from real racist issues and policies,” Emerson said. “Now I’m seeing how that whole trolling process might have worked.”

The event at Stone Mountain took place on April 23, 2016, approximately 25 miles from the 2014 Atlanta recon operation Mueller accuses the IRA of performing. (A U.S. official confirmed to The Daily Beast that Blacktivist aggressively pushed the Stone Mountain rally.)

According to a contemporaneous report from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, demonstrators showed up to confront a group of white nationalists that numbered around two dozen people. At least eight of the counter-protesters were reportedly arrested. CNN reported from the scene that day saying that counter-demonstrators vastly outnumbered the white nationalists and that one of the individuals from the pro-white group allegedly threw a smoke bomb at law enforcement on the scene.

The organizers of the event billed it as “Rock Stone Mountain,” and it was intended to draw attention to Confederate history. It was held days before Georgia’s Confederate Memorial Day. An anti-white supremacy group called All Out Atlanta, was on hand that day as well to counter-protest. All Out Atlanta did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Daily Beast.

The IRA appeared to take notice of this brewing animosity and amplified the event on several of the Tumblr pages it was operating at the time.

David Shepardson/Reuters

A troll farm account whose credentials are listed in the leak, This-Truly-Brutal-World.tumblr.com, repeatedly shared “Not My Heritage” protest advertisements created by fellow IRA account BlackMatters, including rallies in Stone Mountain, and Jackson, Mississippi. An advertisement for the protest in Jackson said it would take place at “14 PM,” and used guillemets instead of quotation marks in the invitation to “Join us for а «NOT MY HERITAGE» rally.”

BlackMatters.Com, another known IRA impostor website, has a section devoted to Not My Heritage protests. The Twitter account @NotMyHeritage, which linked to the protests, was identified as an IRA-backed account in a list released by congressional investigators in November.

The “Not My Heritage” protest in Stone Mountain didn’t just receive press attention from CNN and local papers.

Russian propaganda network RT pushed two videos shot by a network videographer from the day’s events in an article titled “Anti-racism protesters clash with police at Confederate rally in Georgia.” The videos are under the branding of RT’s “video news agency” Ruptly.

In the story, the propaganda network repeatedly blames anti-racist protesters for violence.

“Tear gas and stun grenades were used, and arrests were made—but none on the Confederate side,” the article accompanying the video reads.

In the same month, based on the Internet Research Agency leak, Blacktivist appeared to have reached out to actual or potential attendees of an April 2016 rally for India Cummings, a black woman who died suspiciously in police custody, in Buffalo, New York.

When Dierra Jenkins, a Buffalo-based woman active in the local civil rights community, first came across Blacktivist, she thought its heavy concentration of Buffalo-focused content meant its creators were local. She was named in the Internet Research Agency leak, and confirmed to The Daily Beast that the account contacted her about the Cummings rally. “I do a lot of activist work in Buffalo,” Jenkins said. “Whoever was running that page, I thought, was from Buffalo, because they were posting stuff that was happening in Buffalo.” (An attorney for the Cummings family, Matt Albert—who is not named in the leak—was familiar with Blacktivist, but said the impostor account had no role in setting up any demonstrations on Cummings’ behalf.)

Shortly before the protest, Jenkins said, Blacktivist’s Facebook page contacted her over Messenger, with “no indication why,” to send her an invitation to the demonstration. She was familiar with the Blacktivist page but hadn’t previously interacted with it or anyone affiliated with it—making it likely that the Russian impostors were fishing for attendees based on similar interests visible on Facebook.

Another person identified in the leaked IRA documents, Rochester attorney and activist Craig Carson, said he interacted with Blacktivist in approximately three to five conversations, primarily through Facebook’s Messenger function, though he had a vague recollection that the account might have left the occasional comment on his page after he posted Blactivist material. The conversations took place around the April rally for India Cummings, and for Carson, Blacktivist had a specific request: to print out flyers with their visuals to bring to the rally.

“It seemed like they were reaching out to me because they knew I’d be active, that I’d be at the protest or the demo—‘Be sure to print this out,’” Carson recalled, and he distributed the flyers.

Carson couldn’t deny that the material was useful and contributed to his own desire to see justice for Cummings’ death in custody. Yet several things about Blactivist seemed off to him. No one in western New York’s social justice community knew them, and yet Blacktivist’s Facebook page had tens of thousands of Likes. They seemed to be spouting Black Lives Matter buzzwords without understanding their meaning.

So Carson tested his Blacktivist interlocutor. What was his or her favorite Prince record? What kind of syrup did they like on their pancakes? The account wasn’t prepared to go off-script—though Carson remembers that Blacktivist said it was partial to Purple Rain.

“They kind of stepped in the shoes of someone who’d make a protest sign or visual PDF for your Facebook event page. It never really struck us as odd or out of place, it was genuine help, but it was weird, like, who the fuck are you?” Carson said. After a few weeks’ worth of India Cummings-centered actions, Blacktivist disappeared from the western New York civil rights community as quickly as it arrived, Carson recalled.

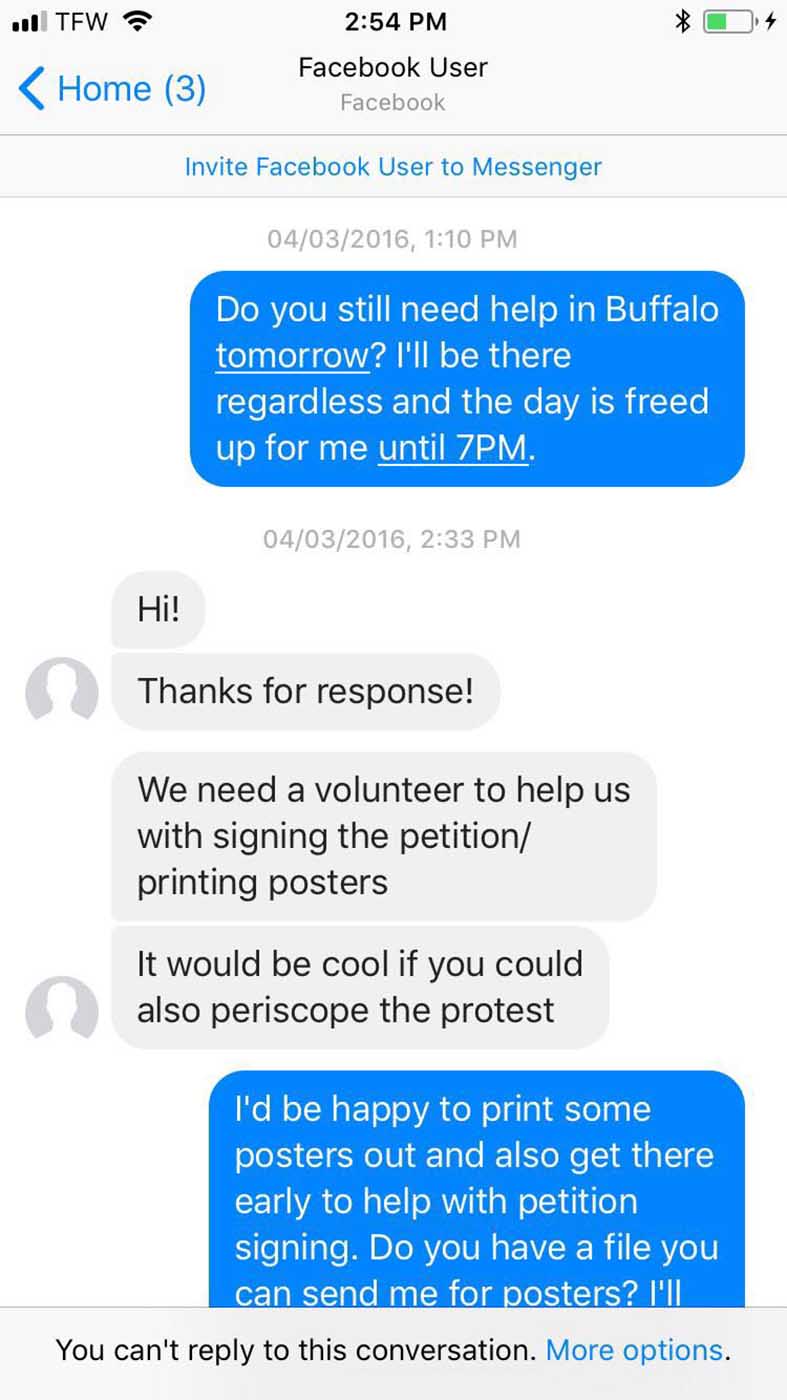

Noah Westfall, another person named as being contacted by affiliates with the Internet Research Agency, lives in Buffalo, New York. In 2016, he wanted to participate in the April protest at the Erie County Holding Center on Cummings’ behalf. Prior to the protest, he had an interaction with a now deactivated Facebook user about the event.

According to screenshots of the alleged conversation provided by Westfall to The Daily Beast, he was messaged on April 3 in the afternoon and told “We need a volunteer to help us with signing the petition/printing posters.”

The user also informed Westfall: “It would be cool if you could also periscope the protest.”

He was subsequently sent a petition and a set of posters to use and was encouraged to put them on cardboard.

The user also added that they had “two more volunteers who have the printed petition too so it would be cool if you cooperate with them so that we won’t have 3 different petitions signed.”

Ultimately, Westfall did not attend. Three weeks later, the user sent a link to another Facebook event and said “you are welcome to attend our protest, on Monday, May 2.”

Westfall had no way of knowing that his interlocutor was not who he said he was, and wouldn’t be at the rally the Internet Research Agency had seen fit to co-opt.

—with additional reporting by Josh Russell, Adam Rawnsley, and Kevin Poulsen