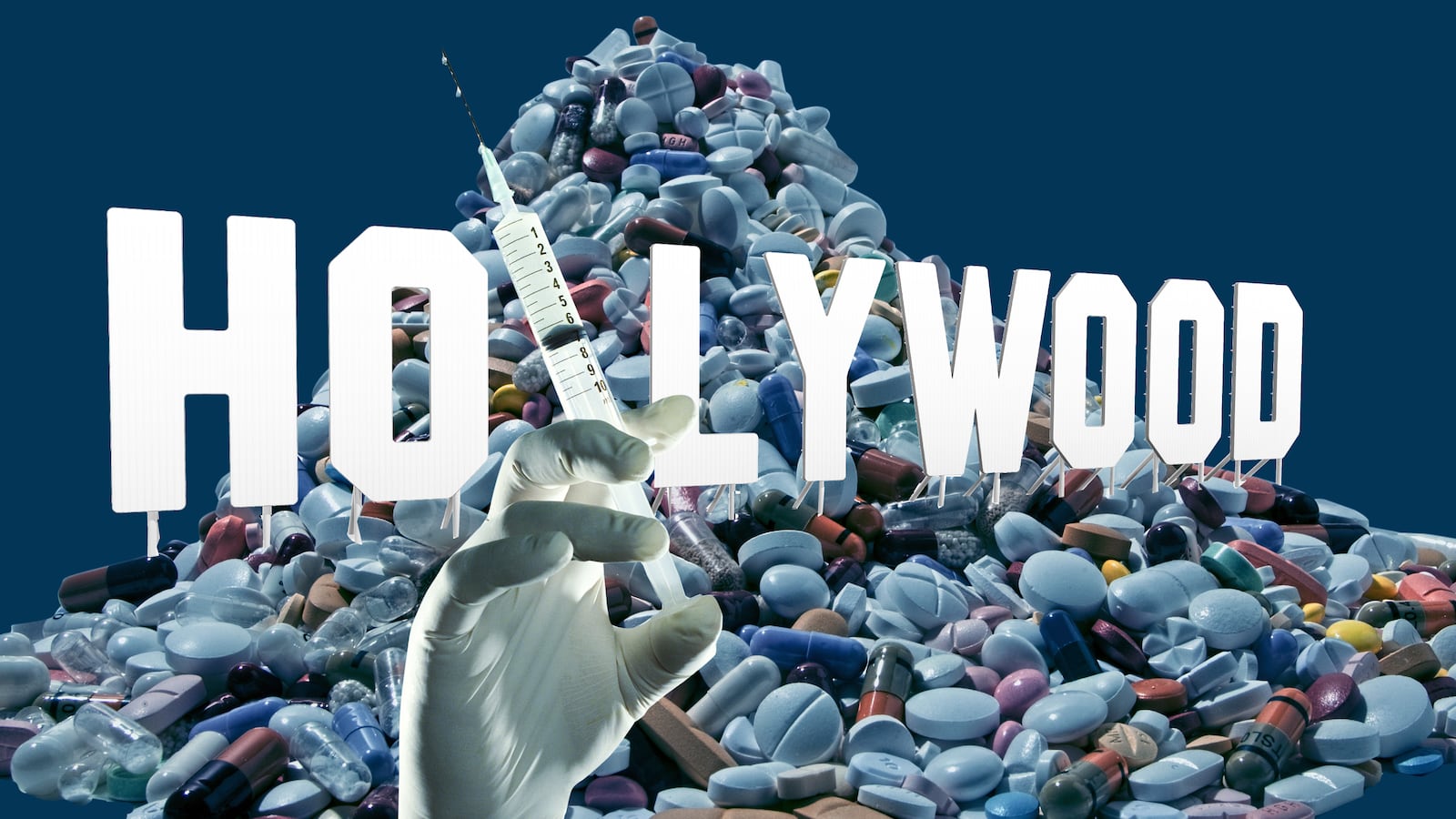

The opioid epidemic has claimed numerous celebrities, marking a new nadir of entertainment-industry addiction. Certainly, we need to talk about Heath Ledger, Prince, Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Lil Peep, and Anna Nicole Smith, to name just a few A-list overdosers. But what is the right way to cover it, the appropriate way to shine a light on these Hollywood tragedies while underlining the fact that most victims of this epidemic aren’t superstars? Is it a tonally aggressive Reelz special, hosted by Nancy O’Dell, in which Variety and E! News reporters relay autopsy details augmented by the commentary of a man who goes by “Dr. Hollywood?”

Fatal Addiction: Hollywood’s Secret Epidemic, which premiered on Wednesday night, is built around a perceived tension at the core of the entertainment industry: widespread celebrity addiction, juxtaposed with the lavish party lifestyle that’s often glamorized in Hollywood productions. The special lists “offenders” like Ted and Superbad in the same ominous tone it uses to read out celebrity overdoses, insisting that these films beat “drugs make you cool” messaging straight into the soft, developing brains of our nation’s youth. This overdone argument could also be seen as hypocritical, coming from a sensationalizing special that occasionally careens into lurid true-crime territory.

When Fatal Addiction tries to go big, like making sweeping arguments about the societal effects of binge-drinking in high school comedies, it falls short. But the special shines in the details, when it takes the time to draw out historical patterns and offer crucial context for modern-day cases. After all, the experience of an addict in Hollywood is a specific one. Some of the conditions are constants, and Fatal Addiction reaches as far back as Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe for examples of young stars who were fed pills in order to perform. “There are stories about young starlets being given Adderall so they can keep going and stay thin,” one talking head chronicles.

Mariel Hemingway, who (in)famously starred as the 17-year-old girlfriend of Woody Allen’s middle-aged protagonist in Manhattan, speaks to the widespread drug use she witnessed as a teenager in the industry. As a teenager filming Personal Best, Hemingway recalls, “There was so much drug use on that set, it was kind of mind-numbing. And as a kid, you’re not sure how to negotiate that.”

The various “experts” charged with tackling this huge topic offer a number of insights into Hollywood addiction. In the timeless category, there’s the pressures of fame, the physical demands of filming a blockbuster movie or putting on a concert tour, and the many enablers who are happy to hook stars up, privileging their own access over the well-being of another human being. There’s opining that pills are appealing because they offer privacy in the social media era, where footage of a starlet using drugs could be sold for a small fortune. Elvis is named as “the poster child for prescription pills in Hollywood,” who woke other Tinseltown denizens up to the reality that these drugs could kill. The special fast-forwards to the ‘90s, offering some context on the explosion in painkiller prescriptions and overdoses. Experts like Dr. Drew Pinsky and Dr. Robert Huizenga (“Dr. Hollywood”) call out over-prescribing and long-term prescribing, as patients were plied with highly-addictive drugs in dangerous quantities.

The opioid epidemic is charged with “killing off some of our biggest stars.” Dr. Conrad Murray, Michael Jackson’s former physician who went to prison for two years for involuntary manslaughter after the pop star passed away, swears that Jackson was already on a cocktail of prescription drugs by the time he was hired, and that he “would do almost anything to get” the drugs he had become addicted to. The (extremely biased) source describes the singer as a “desperate man” in the days before his death. Our very own “Dr. Hollywood” reveals that he had been offered a job as Jackson’s personal doctor, which he turned down when “it became very obvious that writing prescriptions that were not in his best interest was part of the job.”

The arc of Prince’s death is presented as tragically quotidian. The star reportedly started taking painkillers for hip problems; by the time he overdosed, “his house was full of pills, full of opioids.” Fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid, was found in his system. Dr. Drew posits that the majority of celebrity deaths are a result of mixing opioids and benzos (Benzodiazepines) like Xanax and Valium, citing Prince and Heath Ledger. After a run-down of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s tragic relapse, Dr. Drew says that patients who become addicted to prescription pain meds and then are cut off by their doctors can then turn to heroin, explaining, “an opioid addict will go to the streets.”

To share his own experience of addiction and recovery, Fatal Addiction has conscripted The Hills’ Jason Wahler. The reality TV star recalls over a dozen arrests by the time he was 23, intoning, “ultimately, the drugs and alcohol took everything from me.” For Wahler, having his addiction “magnified” by the press certainly didn’t help. In its attempts to lay blame, the special often returns to this idea of the overwhelming pressures of fame, the culpability of paparazzi circling their prey. Of course, it’s hard to take this thesis seriously when it’s coming from talking heads who are active participants in the celebrity-media circus. One Variety reporter discusses the surreal experience of covering a hotel party, only to learn that Whitney Houston’s body was lying unconscious four floors above the event. An E! News employee who worked at Us Weekly at the height of paparazzi predation describes it as an “interesting time” in entertainment media, adding, “We didn’t know if Britney was going to live or die.”

Messages left by fans outside the Paisley Park residential compound of music legend Prince in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on April 21, 2016.

Mark Ralston/AFP/GettyLuckily, the special eventually takes the most culpable to task—pharmaceutical companies and major corporations who profit off of the opioid epidemic, and doctors who facilitated addiction and supplied addicts. It’s posited that doctors treat celebrity patients differently; Anna Nicole Smith’s doctors, as one example, are called out for “unbelievably bad medicine”—a point that could have been made without going into extreme, gruesome detail about Smith’s state at the time of her death. As one cause for optimism, O’Dell celebrates stars like Matthew Perry and Jamie Lee Curtis, who have used their platforms to speak out about opioid addiction. Unfortunately, the special then returns to its flimsy case against allegedly harmful cultural products, calling out Hollywood for a lack of major films about the opioid crisis.

“What will it take for Hollywood to finally take action?” the special asks, as if producing more Oscar-bait films about the dangers of Fentanyl would be sufficient.

To her credit, the E! News correspondent Melanie Bromley insists, “I personally don’t think Hollywood is to blame for the opioid epidemic,” instead blaming the pharmaceutical industry and capitalism in general. In contrast, Dr. Drew’s musings about the emptiness of a social-media obsessed culture and millennials searching for meaning disappoint.

Fatal Addiction isn’t a paradigm of sensitivity and nuance, and often falters when it attempts to propose actionable solutions. But as a history of celebrity addiction and a testament to this particularly deadly era, it’s alarmingly successful.