By Linda Qiu and Jon Greenberg

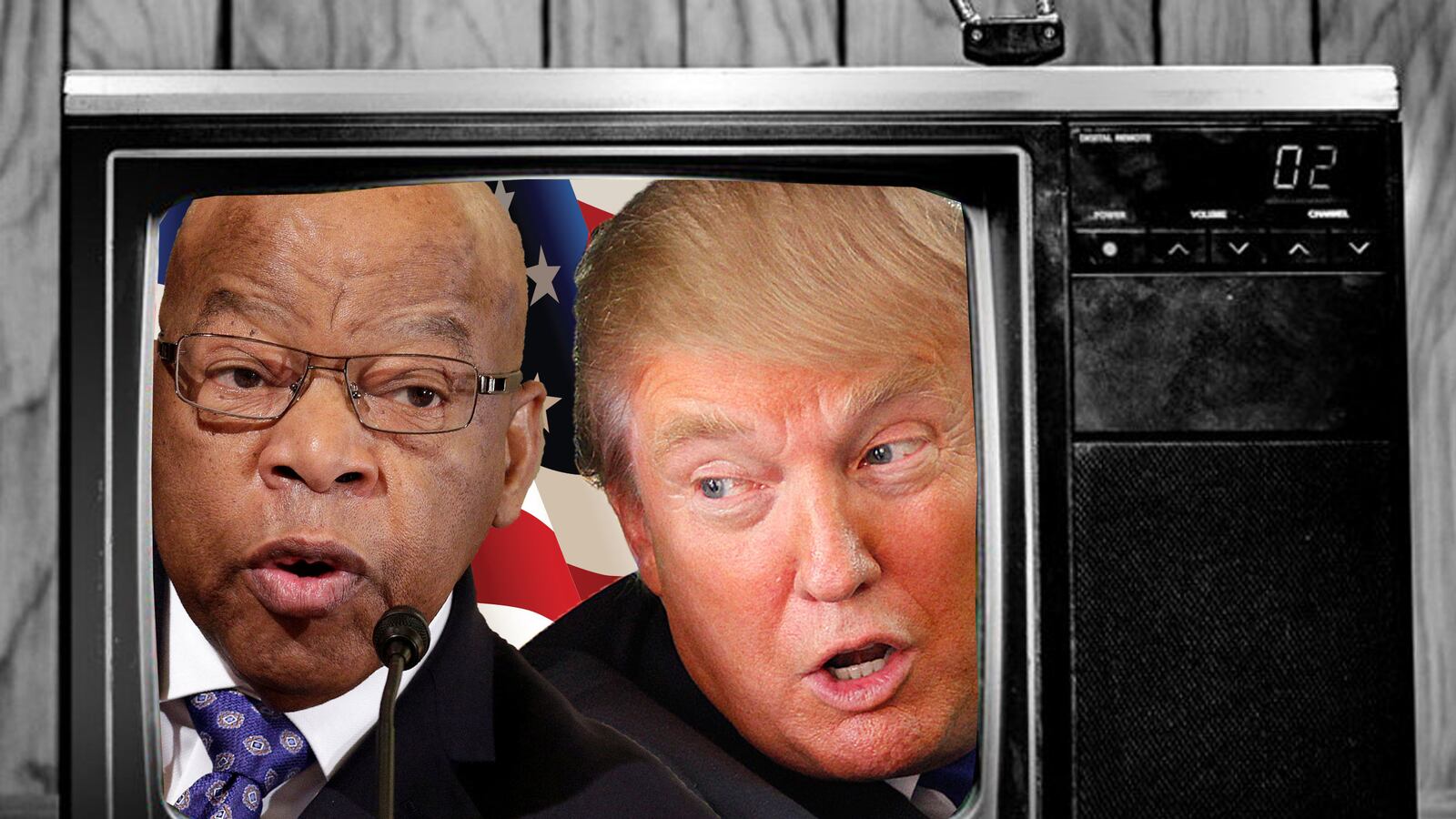

President-elect Donald Trump kicked off Martin Luther King Jr. weekend by sparring with Democratic Georgia Rep. John Lewis, after the civil rights icon said he doesn’t see Trump as a “legitimate president.”

Lewis, in an interview with NBC, said he wouldn’t attend the presidential inauguration because he thought the Russians had helped Trump win election. A few hours later, Trump hit back on Twitter, saying the place Lewis represents is “crime infested.”

As many have noted, Lewis has had a long record of action, including dozens of arrests dozens of for protesting segregation, enduring violence at the hands of state troopers and leading the fight for racial justice in the 1960s.

But is Trump right that Lewis’s district today isn’t doing so hot?

A transition team spokesman referred us to the district’s unemployment, poverty and crime rates. While they are higher than the national and state averages, they’re not much higher. Calling it “crime infested” is a stretch. The statement rates Mostly False.

Georgia’s 5th congressional district, which Lewis has represented since 1987, consists of most of Atlanta (Fulton County) as well as parts of the surrounding suburbs (DeKalb and Clayton counties).

To get a sense of how Georgia’s 5th is doing, we looked at the Census Bureau’s My Congressional District service, which compiles federal demographic and socioeconomic data.

The district has higher unemployment and poverty rates than the national and state averages and a lower median income, but not by that much. On the flip side, it also has a higher rate of education attainment.

Atlanta, the heart of the district, is a major international transportation hub and one of the fastest growing places in the country. Forbes named the city the ninth best place in America for businesses and career development, and among the best for job growth and education.

The Brookings Institution’s Metro Monitor report — which measures economic trends in 100 U.S. cities like job and wage growth, poverty and gross metropolitan product — placed Atlanta at No. 32 for growth (though it ranked at No. 62 and 63 for prosperity and inclusion, respectively) in its January 2016 report.

A separate analysis by PNC Financial Services noted Atlanta’s “tech and corporate cluster” and its “economic dynamism.” (Sixteen Atlanta companies, including Coca Cola and Delta Air Lines, made the Fortune 500 in 2016.) Longer term, the financial analysts concluded, the city will be “an above-average performer.”

In sum, Trump is exaggerating when he says Georgia’s 5th is “falling apart” by some metrics and, by others, he’s flat-out wrong.

What about his parenthetical swipe at the dangers of living in Lewis’s district?

Crime is not reported by congressional district so we’ll have to look at the Georgia 5th’s constituent parts.

As the Trump transition team accurately noted, Atlanta had the 14th highest violent crime rate in 2015 with 1,120 violent crimes per 100,000 residents. That’s about triple the national average: 372.6 offenses per 100,000. (We should note the FBI cautions against ranking and comparing crime rates across cities.)

But that ignores the fact that Atlanta’s violent crime rate, as well as property, has been decreasing over the past decade, mirroring the overall national trend.

While Atlanta does make up most of the Georgia’s 5th, the district does contain parts of other towns with lower crime rates. For example, Brookhaven in the northern tip had a violent crime rate of 327.9 in 2015, and Morrow in the southern end 574.6, according to FBI statistics.

Residents of Lewis’ district did not agree with Trump’s depiction of their neighborhood, and rallied to defend it on social media.

The Atlanta Journal Constitution highlighted the reactions on its front page Sunday morning, emblazoned with the headline: “Atlanta to Trump: ‘Wrong.’” And in 2007, when Trump was looking to add his name the city’s skyline, he seemed to have a very different opinion of it, according to a 2015 Journal Constitution article.

“Atlanta is one of those cities that won’t be suffering the real estate foibles. Atlanta is like New York. New York is as hot as it ever has been,” Trump said. “It’s just going to get better.”

(That year, the violent crime rate was 1623.8, about 45 percent higher than it was in 2015.)

A day after his initial tweets, Trump broadened his claim and said Lewis should focus on “crime-infested inner cities of the U.S.”

Rand Paul on Medicaid

On the Sunday shows over the weekend, U.S. Senator Rand Paul (R-KY), discussed Republican plans to repeal the Affordable Care Act. One of the key issues is how to get rid of the sweeping health care law without creating chaos for an estimated 20 million people who gained insurance under the program.

That includes many people who gained health care through more generous rules for Medicaid, a longstanding federal program for the very poor. Paul said dealing with people who got Medicaid is “the big question.”

“The vast majority of people that got insurance under President Obama's Obamacare, the Affordable Care Act, got it through Medicaid,” Paul said on CNN’s State of the Union.

Paul proposed that if any state wants to retain expanded Medicaid, it should be prepared to raise taxes to do so. Paul’s federal plan emphasizes reducing insurance regulations to lower prices and promoting health savings accounts.

Our focus is on his statement that the vast majority of the newly insured under Obamacare came through the Medicaid program. We were curious if that was accurate.

More people became eligible for health insurance through Medicaid after passage of the Affordable Care Act. The law expanded eligibility for the poor, though states could choose not to participate in the expansion.

We reached out to Paul’s office for his source and did not hear back, but the U.S. Health and Human Services Department issued a report in March 2016 that at first glance gives some support to his claim. It said that Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) added 14.5 million people by the end of 2015. (That’s the most recent data available.)

Take that number at face value and about three-quarters of the newly insured came through the two closely linked programs.

But the analysts we reached told us that a fair number of those new people were eligible for coverage under old rules that predated the Affordable Care Act, and that parsing the numbers is complicated. Paul’s statement rates Half True.

The Kaiser Family Foundation broke down Medicaid eligibility into about 10.7 million newly eligible and about 3.4 million who were eligible before but hadn’t enrolled.

Joan Alker, a research professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, told us that most of that 3.4 million are children. She said Medicaid analysts explain this through the “welcome mat effect.”

“There was a lot of outreach and publicity, and people started coming in,” Alker said. “The parents might qualify for expanded Medicaid, but their kids were already eligible under Medicaid or CHIP. And the same could happen for parents who signed up through the marketplace.”

The marketplace was the way to sign up -- often through a government website -- for individual private insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

It turns out, the impact of Obamacare on Medicaid is more complicated than simply more generous eligibility rules for adults.

Benjamin Sommers at the Harvard School of Public Health said research he and his colleagues did showed that about half of the Medicaid increases came through eligibility changes and about a half through drawing in those who were eligible before.

For Sommers, both effects are part of the Affordable Care Act. In that sense, he thinks Paul has a point.

“The majority of the national coverage gains are Medicaid, but not the vast majority,” Sommers told us.

In an op-ed, Sommers wrote that eligibility rules and the welcome mat effect are so intertwined, if parents lose their eligibility, very often coverage for their kids lapses as well, even though the children still qualify.

“If parents are disenrolled after an ACA repeal, many children will return to being uninsured,” he wrote.

A couple of other factors make it difficult to say precisely why Medicaid grew under Obamacare.

Health care analyst John Holahan at the Urban Institute, a Washington-based academic center, noted that the Medicaid enrollment data is shaky.

“If all 50 states send in their numbers, 40 of them might do a good job and for 10, the data might be garbage. You try to impute and make estimates to account for the flawed and missing information,” he said.

And Laura Wherry, assistant professor of medicine at the UCLA School of Medicine, said any model depends on some guesswork as to what would have happened if the Affordable Care Act hadn’t happened at all.