Months since it took effect, Gov. Ron DeSantis’ signature law to censor books in Florida schools has found an unintended target: his own book.

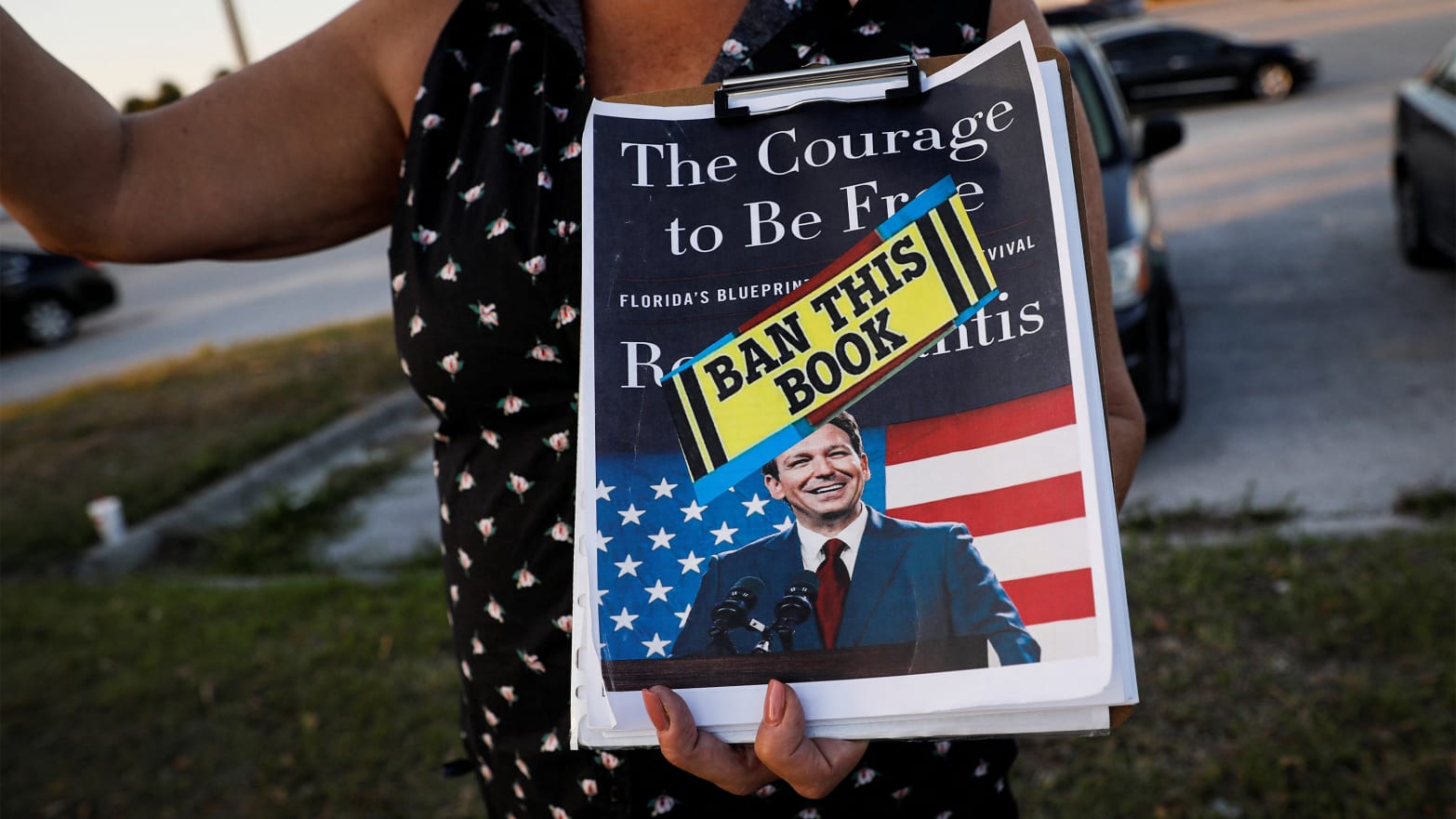

In a clever bit of trolling, Florida Democrats are subjecting DeSantis’ new tome—“The Courage To Be Free: Florida’s Blueprint for America’s Revival”—to the rules that he and GOP lawmakers established to weed out books with allegedly inappropriate content on race, sexuality, and gender from school libraries.

Fentrice Driskell, the minority leader in the Florida House, is leading an effort across 50 counties to see if any of them might review or ban DeSantis’ book based on his law’s vague and unwieldy criteria.

“The very trap that he set for others is the one that he set for himself,” Driskell told The Daily Beast on Monday.

At the very least, the move draws attention to how HB 1467’s vague and arbitrary language can be abused when taken to its logical conclusions—while putting a critical spotlight on the contents of the book, widely seen another clear sign that DeSantis will run for president in 2024.

Florida educators’ struggles to adapt to the law’s confusing rules have received national attention for their apparent absurdity.

In February, for instance, Duval County schools removed a book detailing baseball legend Roberto Clemente’s life—based on its references to the racial discrimination he faced. The fiasco prompted DeSantis to assert that schools were overreacting to the new guidelines.

In that vein, Driskell and fellow Democrats identified 17 instances in “The Courage to Be Free” that could potentially violate Florida law.

For instance, DeSantis used the terms “woke” and “gender ideology” 46 times and 10 times, respectively, both of which could constitute “divisive concepts” the governor has argued should stay out of curricula up to the college level.

On page 125, DeSantis—who asserts he wrote the entire book himself—describes students being forced to “chant to the Aztec god of human sacrifice,” an outdated claim from a proposed ethnic studies curriculum for K-12 students at a California school district.

The same page also references a video showing “dead black children, dramatically warning them about ‘racist police and state-sanctioned violence’ who might kill them at any time.”

DeSantis describes systemic racism on page 127, along with a summation of the New York Times’ “1619 Project,” both of which have already constituted grounds for removal in Florida school districts.

The book has several depictions of violence, another category under the law that can prompt formal review. That includes a graphic depiction of the shooting of Rep. Steve Scalise (R-LA) at a congressional baseball practice in June 2017, as well as descriptions of “BLM riots” with references to looting, assaults against police officers, mob violence, and deaths.

It’s unclear how widely available DeSantis’ book, which was officially released on February 28, currently is on the shelves of Florida school libraries.

One school district—Marion County, north of Orlando—actually responded to Florida Democrats’ complaint. Authorities wrote to thank them for “expressing your concerns” about the DeSantis book.

But they said no school in the county, which is home to roughly 400,000 people, possesses the book. “At this time, our schools do not have any copies of this book in their collections and as such we are unable to evaluate the work as a whole to assess your objections,” an official wrote back in response.

Representatives for DeSantis did not return a request for comment.

The Florida governor has yet to launch a 2024 presidential bid, though he is expected to do so sometime this year. His book promotion tour, which has served as something of a dry run for his campaign, has coincided with a slump in the polls and, as first reported by The Daily Beast, the first staffing shakeup in the nascent DeSantis operation.

But should the governor run, his advocacy for what he describes as “parental rights” in education is poised to form a pillar of his campaign. In Florida, DeSantis has gone so far as to endorse school board candidates who backed his platform of government intervention in public school syllabi across age groups.

Of DeSantis’ 30 picks for school board races, 24 of them won last year. The governor himself, meanwhile, cruised to re-election, as the Florida GOP delivered an across-the-board shellacking to their Democratic counterparts.

Few policy projects have been more central to DeSantis’ brand as an education culture warrior than HB 1467, making it a natural target for Florida Democrats.

Driskell explained she and her colleagues came up with the idea to subject DeSantis’ own book to the censorship law long before it was released. They operated under the assumption that, at the very least, he would refer frequently to topics that are covered under the law, such as “wokeness” and gender ideology.

Particularly with the drop in Democratic turnout that helped DeSantis cruise to reelection, Driskell said the onus is on Florida Democrats to not rely solely on attacking the Florida governor.

“With this objection to much of the material in this book, we’re leaning into one of his weaknesses,” the Democratic leader said. “So we’ve tried to be more strategic about that in the affirmative, and talking about the things that Democrats stand for: The freedom to be healthy, prosperous, and safe, and the policies that support that.”

Driskell added that polling shows parents are largely not fans of government interventions such as book banning, but the rest of the country hasn’t had to deal with a law like DeSantis’.

“If America doesn’t want Florida’s present reality to become America’s future reality, people need to know what it’s like here,” Driskell said. “This is our way of fighting back, but also highlighting how ridiculous some of this becomes, right?”