Nour* fled Baghdad this week after a threat to her life. As an American green card holder, she is a prime target for terrorists.

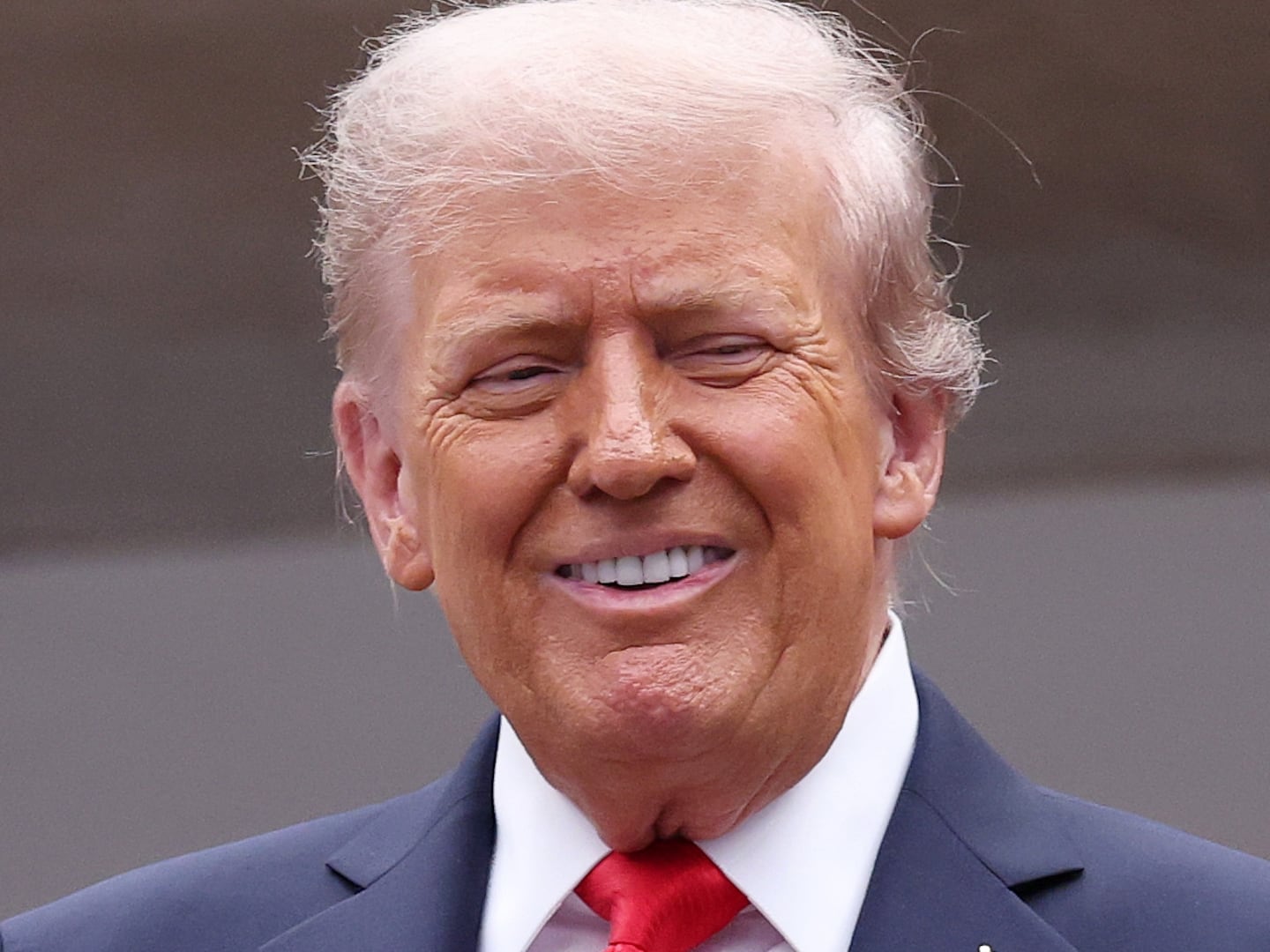

President Donald Trump’s unexpected immigration ban has trapped her in a dangerous position. As an Iraqi, she’s been forced into hiding while waiting for a viable path back to the United States.

“I really feel unsafe now,” she told The Daily Beast. “Me being around as a resident of the United States would make it way more dangerous than it used to be, with ISIS around—anything could happen here because it’s not as safe as we think it is.”

She was caught in Iraq when Trump suddenly signed a confusing order banning many Iraqis from the United States. At the time, she had traveled to Iraq to address some unfinished business relating to her father's death.

In the ensuing mayhem, her flight back to the United States was canceled. And as of Wednesday, no airline will book Nour a flight back to the United States due to the ambiguity surrounding the president’s order.

For Nour and tens of thousands of others waiting to legally come to the United States, Trump’s ban is not just an abstract middle finger to the Statue of Liberty—it has been a personal tragedy.

The erratic, confusing presidential order, signed Friday, halted the American refugee program and temporarily prevented citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries from entering the United States. The White House had not coordinated with the agencies that would be implementing it, leading to mass confusion about who it would affect, and questions about its legality.

Nour and others are now trapped overseas due to a poorly thought out executive order that has been criticized as being simultaneously too broad and not precisely targeted to the problem of terrorism. For example, the ban prevents friendly immigrants from entering U.S. while saying nothing about many countries that have historically been a source of terrorists.

The Assali family, a group of Syrian Christians, waited 14 years to sponsor six of their relatives to join them in the United States. Trump’s executive order was issued during their 15 hour flight to the United States.

After being detained for two hours, they were sent back on a plane to Syria.

"They're distraught over the outcome, and they feel like they have been betrayed," Jonathan Grode, a lawyer for the Assali family, told The Daily Beast adding that the executive order led to a "feeling of helplessness that has caused a lot of anxiety.”

So while some have labelled Trump’s executive order as a “Muslim ban,” many of those caught in its web are of other religions: minority Christians and Yazidis are also subject to the ban, which has created immense instability and insecurity for those seeking to immigrate to the United States.

“These persecuted peoples have not been given a special status yet by the U.S. government for entry,” said Philippe Nassif, executive director of In Defense of Christians, a group that advocates for Christians in the Middle East. “The unintended effects [of Trump’s order] are that minorities such as Christians and Yazidis currently experiencing genocide... are unable to enter the United States because of the ban.”

Ahmed* is one such Yazidi refugee. His house, in Iraq’s Sinjar province, was burned down. His cousin and his cousin’s sons were killed for working as interpreters with the U.S. Army. He has been displaced since 2014, and has applied for refugee status in the U.S., but Trump’s ban halted the U.S. refugee process—with little indication of when it might begin again.

“Trump’s order stopped everything… We can’t go back to Sinjar, our house was burned. We lost everything. And there [are] political and ethnic tensions there," he told The Daily Beast. “Our lives as minorities in the Middle East became under a greater risk especially after Trump’s order.”

Ironically enough, some of the immigrants caught up in the ban have been fans of Trump.

The Assali family, Grode said, is a Christian family that has been generally conservative. And Nour, the green card holder trapped in Iraq, was sympathetic to Trump—until now.

“At first I thought Donald Trump could be a good chance for the [United States] to improve the country’s economy and offer better chances for all,” she said. “But with this order everything is going way worse, leaving every person who is related to any of the countries mentioned in a huge confusion, [unsure about] what’s going to happen next.”

While Trump’s ban was ostensibly to reduce the risk of Islamic terrorism, there is evidence that suggests his broadly-configured order actually hindered efforts to fight groups like ISIS.

There are currently Iraqi pilots in the United States, training to fight terrorism alongside U.S. forces. Had they arrived a week later, they would have fallen under Trump's ban. And if they leave, neither they nor other Iraqi forces will be allowed to come back into the country under the current terms of the executive order.

"At the point that the president signed that order into law, we had Iraqi pilots, with Iraqi passports training to fly aircraft in the United States, who are going to go back to Iraq and fly alongside our people to attack terrorists," said Democratic Sen. Tammy Duckworth, an Iraq War vet who is a double amputee due to a rocket-propelled grenade that hit a helicopter she was co-piloting.

It’s a bipartisan concern: Republican Sen. John McCain also expressed frustration over the presidential order—Iraqi pilots are currently training in his state of Arizona.

"We need that training very badly. We need to have them training so they can protect American lives," McCain said.

“[Trump’s executive order] has wide-ranging effects on our military, on our security, and it's going to hamper our ability to destroy our enemies overseas,” Duckworth told The Daily Beast.

Nearly one week after Trump’s poorly-managed executive order, the White House and the administration is still trying to fix up this mess: military allies have been alienated, those who love America have had their lives upended, and those who have earned their place on U.S. soil are trapped overseas with their lives at risk.

Meanwhile, the promise of safety? Dubious at best.

*Some of the names used in this story have been altered in order to protect identities. As refugees, they face a personal risk if identified by their own names.

—with additional reporting by Saud Murrani