Sean Connery’s legacy will forever be defined by his seven turns as Ian Fleming’s dashing British spy, James Bond. Yet the illustrious Scotsman, who passed away this morning at the age of 90, was far more than simply 007, as evidenced by a renowned filmography that includes gems as varied and stellar as Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie (1964), John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King (1975), Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987)—for which he won his sole Oscar, for Best Supporting Actor—Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), and The Hunt for Red October (1990). Yet perhaps none of his post-Bond performances are as electrifyingly macho, humorous and purely Connery-esque as his turn in a 1995 action extravaganza that’s as outsized and entertaining as his iconic persona.

Yes, I’m referring to The Rock.

Before Michael Bay became wholly invested in orgiastic celebrations of CGI spectacle, lewd titillation, and the military industrial complex, he crafted one of the ‘90s preeminent blockbusters with The Rock, the story of a rogue marine Brigadier General named Frank Hummel (Ed Harris) who decides to get payback against the U.S. government by taking control of Alcatraz and threatening to launch chemical weapons-enabled rockets at San Francisco if his demands aren’t met. To counter this insane insurrectionist threat, which is complicated by the fact that the island prison is famous for being a fortress no one can break out of (or into), the American powers-that-be take a preposterous course of action, pairing goofy chemist Dr. Stanley Goodspeed (Nicolas Cage) with the only individual to have ever successfully escaped Alcatraz: former SAS Captain John Patrick Mason (Connery), who as a reward for his unmatched feat has been locked away in secret for two decades.

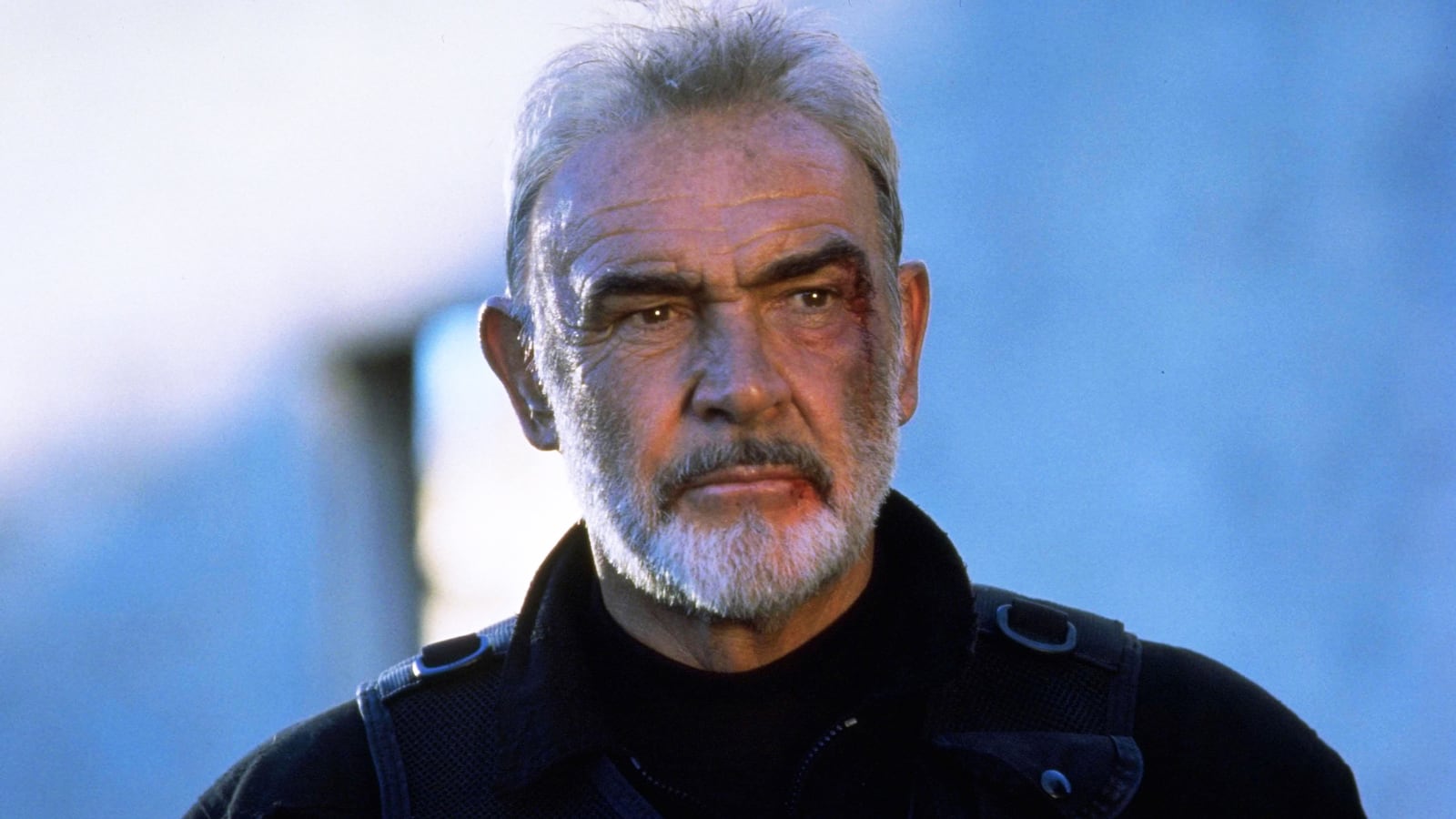

Suffice it to say, this is only-in-the-movies nonsense. But it’s very good nonsense, since it hinges on an outrageous villainous plot, a ludicrous heroic mission, and a protagonist whose stature is downright mythic. To that end, it’s the perfect late-career role for Connery, who by this point had long established himself as the epitome of manly cool. Bay introduces him in heavy shadows and streaming lights, his hair stringy, his beard scraggly, and his eyes alight with cunning ferocity, and Connery immediately imparts a sense of Mason as a caged lion—the king of the jungle, just waiting for a chance to strike and then once again roam the land as its apex predator. And when he shortly thereafter dons a dashing designer suit and receives a haircut on a luxurious hotel suite balcony, the twinkle in his eye makes clear that he comprehends—as we do—that he’s slipping back into the trademark 007-style guise that first made him a superstar.

Thus, his subsequent assault on his handlers and daring escape off said balcony feels almost preordained, and like an inside joke for cinephiles worldwide. What, you expected THE Sean Connery to be the lackey of some clownish bureaucratic stiffs? One of the chief pleasures of The Rock is the way the film and Connery constantly tip their hand about playing to—and off of—the headliner’s reputation as the embodiment of rugged, cocky, suave masculinity. Nowhere is that more pointedly felt than in Mason’s dynamic with Goodspeed, who as portrayed by Cage (in the role that transformed him into a badass-cinema luminary) as a stuffy geek who’s out of his element in this testosterone-drenched saga, and yet also a ladies’ man with more grit and wit than is initially apparent.

Connery relishes not only the opportunity to be the pinnacle of cool in The Rock, but to do so in a story that requires him to berate and emasculate Cage’s sidekick as well as to train him as his protégé. He’s simultaneously the lone warrior and the mentor, reasserting his peerless machismo and also passing it on to the next generation. In both respects, Connery is in his element, whether chastising his co-star’s nerd for crying about trying his best (“Your best? Losers always whine about their best. Winners go home and fuck the prom queen”), confidently facing off against Harris’ disenchanted would-be terrorist, or showing hard-earned appreciation for Goodspeed’s final act of kindness. And the fact that the film also gives his Mason a measure of soulful regret and fury over his lost life—which he attempts to grapple with during a tentative reunion with the daughter he hasn’t seen in years—only further allows Connery to flex his diverse muscles, and to cast Mason as more than merely a one-dimensional cartoon.

Most of all, though, The Rock lets Connery be—thrillingly, hilariously, gloriously—The Man. At no point during Bay’s over-the-top spectacular does the actor seem anything less than in complete control of himself, his circumstances, and the life-or-death task at hand. Sporting the distinguished gray beard of his later years, he’s as handsome as ever at the age of 65, and just as robust, proving to be up to the challenge of swimming through treacherous depths, navigating perilous passageways, and taking on adversaries decades his junior. It’s a performance that screams “He’s still got it,” although that hardly comes as a surprise, since from his entrance to his exit, he radiates the self-possession of a grizzled veteran eager to teach some young pups a few new lessons.

The Rock reconfirmed that no amount of charismatic leading men, or gratuitous aesthetic razzle-dazzle, could overshadow Connery’s larger-than-life magnetism. In that regard, Bay’s sophomore behind-the-camera effort comes across as a tribute to its star, fully aware that he’s far burlier, sexier, and more awesome than anything else complementing him on screen. And recognizing this, Connery seizes the moment, once again demonstrating the force of personality that made him an all-time Hollywood great.

At the conclusion of The Rock, Connery’s Mason does right by Goodspeed—in a manner that emphasizes his near-magical quality—and then vanishes into thin air. It’s a fitting fate for a borderline mythological character played by a legend equally comfortable inhabiting, and poking fun at, his own idealized persona. It may not be his absolute finest work, but it’s arguably his most fun.