TOKYO—The state funeral for Japan’s longest-reigning prime minister, Shinzo Abe, is set to take place on Tuesday.

The majority of the public opposes having the lavish funeral and many in Japanese society are increasingly critical of his time in office. Even in his own Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), where he ruled with an iron fist for almost a decade, lawmaker Seiichiro Murakami stunned the press by stating very publicly last week, “I always opposed a state funeral for Abe and I won’t attend. His administration wrecked state finances, the economy, diplomacy and even the bureaucracy. He was an enemy of the nation, a pirate.”

In the immediate aftermath of his shocking assassination, Shinzo Abe has received tributes for his international statesmanship. Unfortunately, this praise is in sharp contrast to his domestic legacy: a Japan deeply cynical about truth in public life, where almost no one believes what the government tells them.

This aerial view taken from a helicopter chartered by Jiji Press shows police working at the scene at Kintetsu Yamato-Saidaiji Station in Nara where former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was shot on July 8, 2022.

STR/Jiji Press/AFP via GettyPosthumous revelations that Abe and many in his Liberal Democratic Party had close ties to the Unification Church, a problematic cult based in South Korea, have damaged the party. The current PM, Fumio Kishida, has seen his support ratings drop as low as 36 percent. In a bizarre turn of events, there is even growing public support and sympathy for Abe’s assassin.

As prime minister and leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Abe routinely pressured government agencies to give him the results he wanted. He was especially determined to show that “Abenomics,” his much vaunted fiscal policy essentially modeled on Reaganomics, was successful.

The bureaucrats did their best to dress up the results. In December 2018, the Ministry of Labor was exposed for falsifying job data for years; its adjustments had even made wages in Japan appear to be rising, when in fact they were falling. The faking of data was not simply a matter of optics; more than 20 million people were underpaid for work-related benefits as a result.

In January 2019, the conservative newspaper Nikkei and TV Tokyo conducted an opinion survey and found that nearly 4 out of 5 respondents no longer trusted official statistics. Then, in 2021, the Asahi Shimbun, a liberal newspaper that Abe hated, revealed that the Ministry of Infrastructure had falsified construction contract figures for nearly eight years, primarily during Abe’s administration. This illegal action distorted key economic statistics used to compile important indexes such as the Monthly Economic Report released by the Cabinet Office.

We may never know if Abenomics actually worked, because reams of data would have to be reviewed and corrected—something that the current prime minister says he has no intention of doing. What we do know is that real income fell and the gap between the rich and poor widened in Japan during Abe’s tenure. The plummeting value of the yen in recent months may have something to do with international investors’ belated recognition that Japanese government data is more or less worthless.

The roots of the conservative LDP go back to the Cold War, when it was a major financial and political beneficiary of the CIA’s interference in Japan to ensure that left-wing parties didn’t make it into government. As the leading party of government for decades, the LDP was never a unified entity. Even today, multiple factions—ranging in their political orientation from center-right to right-wing nationalist—constantly jockey for power. Each faction is led by a charismatic leader to whom junior members pledge allegiance.

Abe essentially led the Hosoda faction, and through a ruthless mix of patronage and ostracism of rivals he made it the dominant one. In 2014, during his second term as prime minister, he consolidated power by nominating close associates to head important government committees and major bodies such as the National Security Council, the Bank of Japan, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

In 2014, he extended this control of government and civil service appointments by creating a Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs. He even appointed cronies to the board of the state broadcaster NHK, turning it from a respected, impartial news agency into what came to be widely derided as “Abe TV.” And he used his media influence to keep potential rivals in his own political party in their place.

A woman holds a placard during a protest against Shinzo Abe's State Funeral in front of Shinjuku Station on September 26, 2022 in Tokyo, Japan.

Takashi Aoyama/GettyBut if you want to know how Abe’s Japan really works, you need to know about the Moritomo Gakuen scandal. In 2017, Kyodo News, a nonprofit news agency, and the Asahi broke a story that the Ministry of Finance had intervened to cut the price, by nearly $8 million, of a plot of land purchased by a right-wing private-school operator, Moritomo Gakuen, who planned to build the Abe Shinzo Memorial Elementary—and appointed Abe’s wife, Akie, as its honorary principal.

The affair did not end with that revelation. In 2018, a civil servant named Toshio Akagi, who worked in a local bureau of the finance ministry, committed suicide. He left behind an extraordinary 518-page collection of documents, known as the Akagi File, detailing every step of the scandal and cover-up.

At first, Abe’s government, which ostensibly held onto the file because it contained official records, denied its existence; only last year did it finally release the documents to the public after a concerted campaign by Akagi’s widow, Masako. At a press conference, the finance minister who had also been deputy prime minister to Abe, Taro Aso, admitted that he had known of the file’s existence for a long time.

The documents showed how Akagi had responded to one email request from the ministry in March 2017 to cook the records on the land purchase. “I am uncomfortable and I feel conflicted about altering documents dealing with a confirmed and concluded matter.” A number of other bureaucrats were implicated in falsifying official records of the land deal, but none were ever prosecuted.

In May 2018, the head of Osaka’s Special Prosecutor Office, Machiko Yamamoto, announced that no indictments were being issued for the 38 suspects involved. She refused to give any details or answer questions. A few months later, Yamamoto was promoted and moved to another office. This put her beyond the reach of the Prosecutorial Review Board which could have interrogated her about her questionable decisions.

Masako Akagi sued the government for compensation over her husband’s death. In December last year, the government settled the claim, shutting the case down.

The poison of corruption and mistrust travels through corporate Japan too. No one from Toshiba has been prosecuted for their part in what may have been the largest accounting fraud in Japan’s history, which emerged in 2015, on Abe’s watch. Last year, Japan’s industry minister breezily declared that his ministry had done nothing wrong when officials colluded with Toshiba, which plays a vital role for Japan’s nuclear industry, to share confidential information about foreign investors.

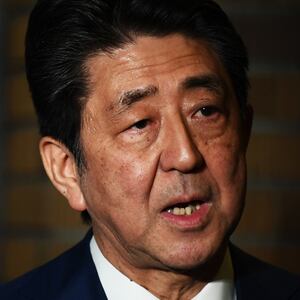

Shinzo Abe speaks at a news conference on May 25, 2020, in Tokyo, Japan.

Kim Kyung-Hoon - Pool/GettyNever let it be said that Abe did not lead by example. When Japan was bidding to win the 2020 Olympics and the world was worried about the radiation from the damaged Fukushima reactor, where a triple meltdown had taken place, Abe declared, “Fukushima is under control.” This could hardly be further from the truth.

Japan will soon begin pumping into the sea thousands of decaying barrels of highly radioactive water that have been stored on site since the clean-up operation that followed the 2011 nuclear disaster. The government claims that this is safe, that the water will be treated; it neglects to mention that this contaminated water contains strontium, rhodium, iodine, ruthenium, and other hazardous materials, which can’t be filtered out.

“You lie as naturally as you breathe,” an opposition party leader once told Abe to his face. On Christmas Day of 2020, in his eighth year as prime minister, he finally admitted it. Abe confessed that he had lied to parliament 118 times, over the illegal use of public funds for a lavish dinner party, and apologized. Although the conduct that forced that apology was entirely characteristic—he was leaving office under the cloud of a criminal investigation into his campaign activities—that statement was a painful admission to part on.

Yet Abe never faced any consequences. He was never prosecuted for a crime, nor were those who covered up for him. And that’s why we have a Japanese government that can’t tell the truth. Lying is rewarded and truth-telling is punished. The government will continue to make up convenient facts, hide inconvenient ones, and hope to be believed. That is part of Abe’s legacy.

Abe left office with his one great ambition unrealized: to cast off the postwar constitution and replace it with a version based on the pre-war imperial constitution that would enable Japan to become once again a military power. It would be one that his former justice minister, Jinen Nagase, declared in 2012 would be stripped of “basic human rights, popular sovereignty, and pacifism.” The legal scholar Lawrence Repeta pointed out that the new constitution Abe wanted to adopt would also eliminate protections for free speech, renounce universal human rights, elevate public order over individual liberties, and give the prime minister new powers to declare “states of emergency” and to suspend constitutional rights and legal procedures.

Even out of office, Abe continued to exert tremendous influence over the party. At the time of his murder, he was exercising that influence by campaigning for the LDP and his faction. That influence gained a posthumous twist with the result of the election that concluded shortly after Abe’s death. The LDP finally secured enough seats in the upper house to make possible his dream of amending the constitution. But will they? Even beyond the grave, Abe still seems to rule the party.

The costly funeral, which the majority of Japan didn’t want, is now over. The question that everyone should be asking now is this: Can the ghost of Abe be exorcized from Japan? And can the nation learn to tell the truth again?