So Congress may be about to leave town for the summer without doing anything about the border crisis. President Obama asked for $3.7 billion in emergency funds. The Senate came up with around $2.7 billion. The House started north of a billion but finally shaved its number down to $659 million. Not much room for compromise there—and indeed it turned out Thursday that the House Republicans couldn’t even pass their own bill! So here’s yet another problem we can’t fix.

To which you may be saying, “Yes, maybe we should do something or other about those kids, but hey, the violence down in those countries, that’s not our problem.” I urge you to think again. It is our problem. We did a lot to create it. And ruminating over that history should make us all shudder to think, as we gaze to the Mideast, what future problems we’re helping to create today.

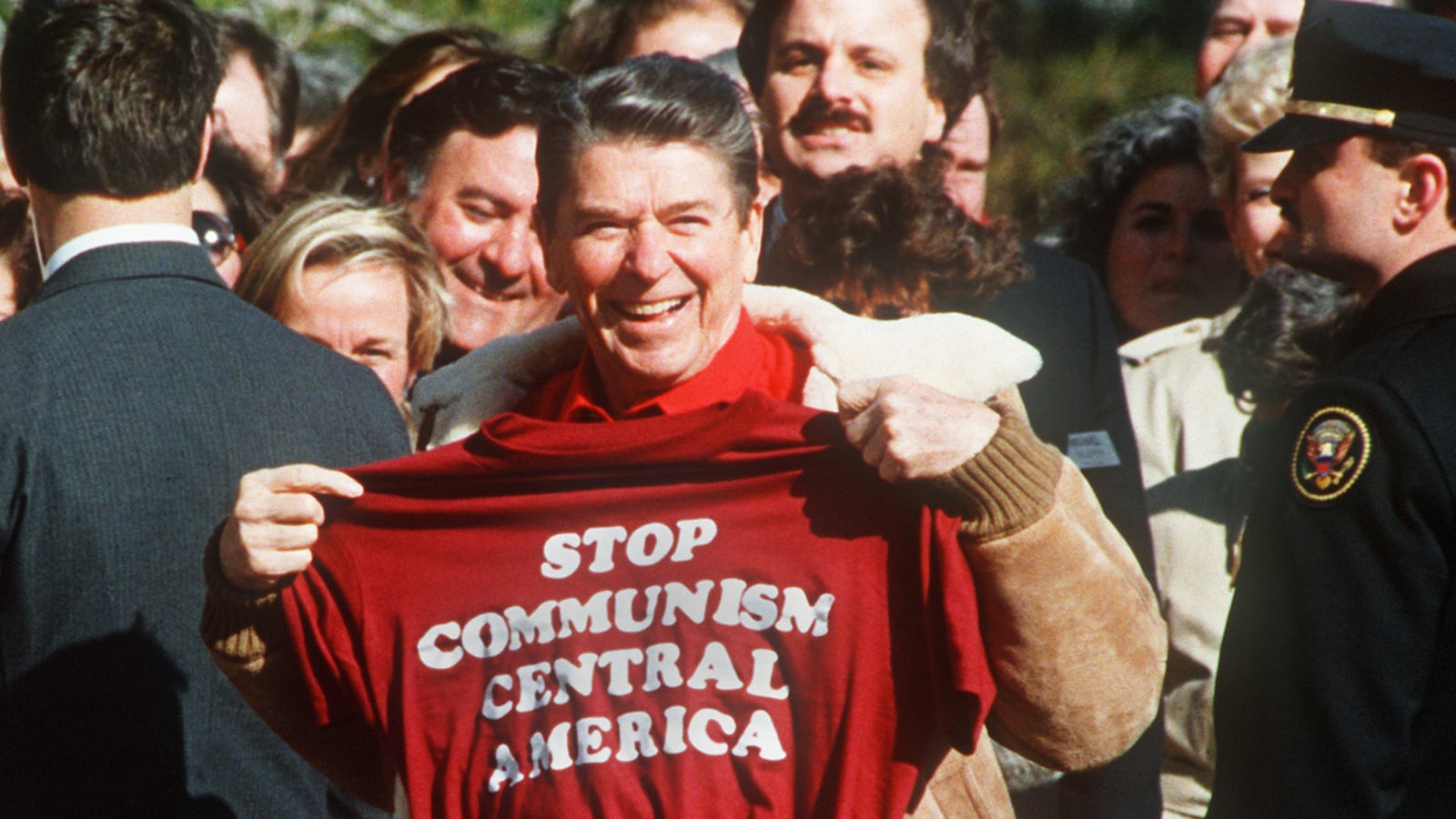

The children are coming from three Central American countries—Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Is it just a coincidence that these are all countries in which the American hand has weighed particularly heavily? Guatemala we just wrecked starting in 1954, with the CIA-directed coup against land reformer Jacobo Arbenz that led to a military dictatorship and, eventually, 36 years of civil war that ended in 1996. El Salvador was, with Nicaragua (more on it later), the focus of Ronald Reagan’s “keep the commies out of Harlingen, Texas” doctrine; a few billion Yanqui dollars poured into the country to arm death squads and perpetuate another wrenching civil war, which took 75,000 lives and ended in 1992.

We haven’t intervened as much in Honduras, although it was, many say, the original “banana republic,” built from a backwater into a major banana producer by American corporate interests who created a small and very conservative elite that ruled the country for decades. Honduras, of course, just experienced a military coup against a populist reform president in 2009, a coup that the Obama administration, to its lasting discredit, backed.

Nicaragua, as noted, was also a target of Reagan’s, and we started a hideous cycle of violence there after the Sandinistas had the nerve to overthrow our dictator. But after the Sandinistas agreed to elections in the late 1980s—and the U.S.-backed coalition won, and the Sandinistas peacefully ceded power—Nicaragua pulled itself together comparatively well. And Costa Rica, for a host of historical reasons, has always been more stable than its neighbors.

So in the three crisis countries, or at least in two of them (Guatemala and El Salvador), there’s a pattern: U.S.-sponsored civil wars tore the country apart in the 1980s. What happened next? As Ryan Grim and Roque Planas put it in a terrific Huffington Post piece tracing this history in greater depth, “With wars come refugees.” Terrified citizens of these nations started running to the United States by the tens of thousands.

When they got here, there was nothing for them. Depending on how old they were, they or their kids formed gangs in Los Angeles and elsewhere in the 1990s. We responded to that by “getting tough” on crime, throwing thousands of them in jail. Then when they got out of jail, we deported them back. We escalated the drug war—we had some success in Colombia, which merely pushed much of the cocaine trade into Central America. The ex-gang members we deported created extremely violent societies, societies where 10-year-old kids are recruited into new gangs and threatened with death if they don’t join, and it’s from those societies that today’s children are fleeing.

No, it’s not all the United States’ fault. People make their own choices in life. But we financed civil wars and counterinsurgencies in these countries to the tune of many billions of dollars. It led to massive amounts of death, and many thousands of refugees. The violence that incubated that generation of Guatemalans and Salvadorans took the form of bombs and bullets that were stamped to say “Made in the USA.” And now the children of that violence are risking their lives to flee it. And Congress has left town.

What future crises are we germinating today, 6,000 miles to the east, that we will similarly wash our hands of 30 years from now? God only knows. It seems to me that the main thing being accomplished by the eight-year Israeli blockade of Gaza, supported by the United States (both Bush and Obama), is the creation of thousands of young, angry, militant Palestinians. The unemployment rate in Gaza is 40 percent; for young men up to 29 years of age, it’s near 60 percent. Those are both more than double the numbers from before the blockade. Add this lack of anything resembling opportunity to the inevitability of demography, and Israel, as many have observed, is lighting a fuse (actually, we supply the matches; $3 billion a year’s worth of them) that may look long now but will one day ignite in its face.

A bit further to the east, I’ve read that the Islamic State (the former ISIS) has printed maps in which its black-and-white flag stretches over the entirety of Iraq, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon (one militant says in a recruiting video: “We understand no borders … and we will even go to Jordan and Lebanon with no problems”). Jordan isn’t a particularly free country right now, but it is the first Arab country to have a trade agreement with the United States. Lebanon is in duress because of Hezbollah, but it is comparatively free, with a vigorous press and a long history of intellectual engagement with the West. If these countries were to fall into that darkness, the tragedy would be enormous, to say nothing of having to deal with a reactionary caliphate that ruled over a population of more than 60 million people.

Again, it obviously wouldn’t be wholly the United States’ fault. But, again, our choices have had consequences. The Iraq War that we started unleashed ISIS, and the Syrian civil war that we have done nothing to stop has made it stronger. And if the worst comes true five or 10 or 30 years from now? Well, if the border crisis is our guide, we’ll forget that we had anything to do with it, and we’ll do something new to make things worse still. As Faulkner told us, the past is never dead and isn’t even past.