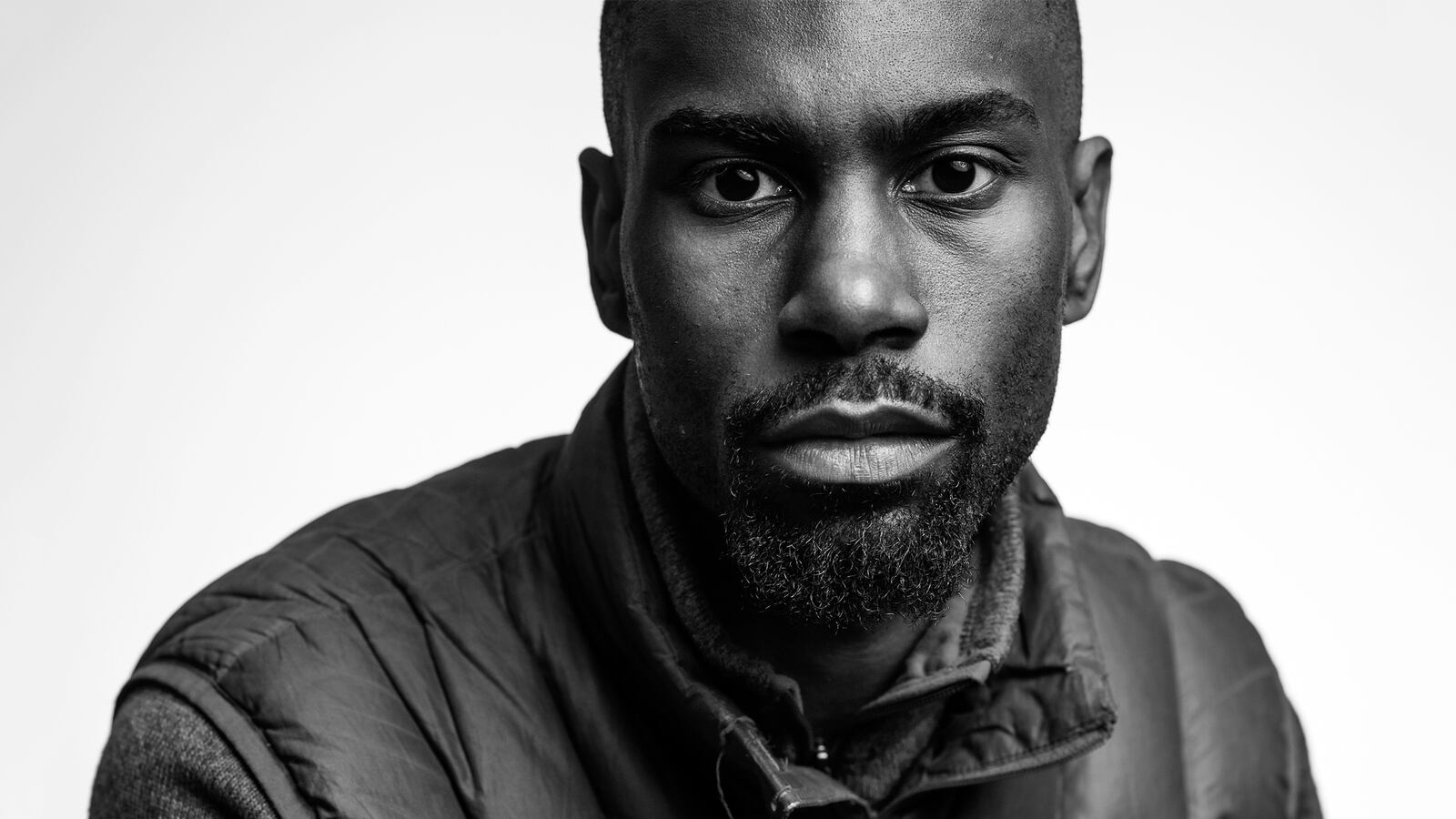

DeRay Mckesson, perhaps America’s most prominent contemporary voice in social justice, is running for mayor of Baltimore, and he’s losing badly.

But people using the city’s mayoral election as a referendum on his efficacy as an advocate, let alone as a measure of the broader impact of the Black Lives Matter movement, are either confused or dishonest.

That a millennial and political neophyte has made himself a more integral part of the national conversation than sitting mayors of some of the largest U.S. cities speaks to the era in which we live.

Mckesson’s late entry into the hotly contested race to replace outgoing Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake caught many by surprise but despite a chorus of devoted volunteers, over 5,400 individual campaign donors, a legion of social media followers and the kind of coverage normally reserved for A-list celebrities, the civil rights activist has lagged in polling of the crowded field.

Ultimately, even if he succeeds in his plan to reach 30,000 voters in the coming days—which would be an unprecedented get-out-the-vote effort—it may not be enough to shock the political class and deliver what would be a stunning upset.

His opponents—or at least their campaign operatives—have publically written him off as a carpetbagger in his own hometown. They openly complain that he has spent less of his adult years in the city than he has gallivanting around the country, courting celebrity CEOs in Silicon Valley, and that “outsiders” are managing his campaign. Little is said of his tenure as a Baltimore public school official, the after-school program he launched, or his campaign’s expansive policy platform. They counted him out almost as soon as he signed his name on the qualifying documents.

Yet, in the final run-up to the April 26 primary, supporters have stuffed themselves into standing-room-only events and, last weekend, 100 phone bank volunteers lit up the lines. For them, Mckesson represents the kind of transformational leadership that is critical to Baltimore’s future.

In the end, his ideological foes—and even some who share his politics—will find it all too easy to dismiss Mckesson, and the movement he helped to ignite, as opportunistic and self-serving. They will point to his frequent appearances on cable news and late-night talk shows, as well as multiple visits to the White House, as evidence of unchecked ambition. Others will grouse about his connections to tech companies and venture capitalists, and about the thousands of dollars in campaign donations that he has received from key executives.

But in a post-Trayvon Martin era, few emerging voices have been as potent and substantive as Mckesson, a native son of Baltimore who rose to national prominence after the police shooting death of Michael Brown in August 2014. Sporting his trademark blue puffer vest, he was one of the lead organizers in Ferguson, Missouri, where he always did more planning than shouting.

While Mckesson by no means acted alone, he quickly figured out how to coalesce what was happening on the ground into an issue-driven, interconnected agenda that would capture the attention of policymakers from St. Louis County to Washington, D.C. And as he moved across the country, appearing at rallies in the wake of other high-profile deaths, Mckesson’s public profile—and his cast of naysayers—grew exponentially. Today, he has more Twitter followers—330,000—than there are voters in Baltimore.

If he was captivating, it was because he spoke to the salient issues of the day with a palpable sense of urgency. If he commanded a seat at the table, it was because he delivered data-driven policy solutions that were tied to a meaningful roadmap and benchmarks. If you listen closely, you can hear some of those proposed social justice reforms echoed by presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton.

The same young man who was once the target of mall security guards now regularly meets with editorial boards, community leaders, corporate executives, and even the president of the United States of America.

That work has proven an attractive lure for people looking for a central rallying figure, someone who could voice their gravest fears and who embodied their most deeply held hopes. But, if they were looking for another Martin or Malcolm, they did not find that in Mckesson—a 30-year-old former educator and son of two recovering addicts who was raised by his father and great-grandmother. As the demonstrations took root and began to spread from city to city, Mckesson was almost painfully deferential to his compatriots. His “we” over “me” approach evoked both an air of humility and an unshakeable confidence in the strength of their solidarity.

“We will win,” Mckesson often tweets.

He and others in the far-flung movement preferred a more amorphous, decentralized form of leadership focused on that “we”—a flat hierarchy, where the voices of the many were valued with a greater intensity than those of the few. BLM has no “president” and no formal “board of directors.”

The approach has proven beneficial, on one hand, empowering and growing a new intersectional generation of activists. On the other hand, it has been costly, in terms of message discipline, resulting in an organizational schism that threatened both the credibility and the viability of the movement itself.

Soon, some of those public battles, fought on and off social media, made their way into the headlines. In once instance, whether out of genuine concern or virulent jealously, New York Daily News columnist Shaun King (that he’s now appearing in a TV ad for a presidential candidate might help answer that question about his motives) chided Mckesson for his visits to the White House. Others were adamant that BLM, writ large, would not endorse a 2016 presidential candidate and believe that their real power rests in holding public officials accountable—not becoming one.

By running for mayor, Mckesson is defying that notion.

The idea that social advocacy can marry the more traditional means of public service while maintaining the integrity of the cause is a time-honored matter of debate. BLM itself was fueled by the idea that transactional politics have led to the decline of U.S. cities, like Baltimore, and that race, gender, and wealth are often informing factors. There is no greater example of this than the 1994 crime bill and related pieces of legislation that sailed through state houses around the country.

In 2015, there were 344 homicides in Baltimore—the bloodiest year per capita— and most of the victims were young black men. Nearly 85 percent of its public school students are “poor enough to qualify for free or reduced-price school lunch” and the median income in the hyper-segregated Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood where Freddie Gray died is just $24,000 a year.

That Baltimore is failing, by nearly every meaningful standard, does not keep its residents from loving the harbor city. It does not keep them from the hope of a widespread economic revival, reforms to its criminal justice system, and revitalized schools. Nor does it keep them from demanding affording housing, quality basic public services, and safe spaces for their children.

But, as Mckesson has surely encountered, change and their agents are not easily embraced. Big-city mayors are more typically elected based on the dominance of political machines that have been entrenched for decades. Upending the system means convincing voters that it can be done. Mckesson calls that a “belief gap.”

Through his advocacy, Mckesson has played a critical role in filling that gap for the millions of Americans who believe that social justice is attainable.

The question remains: Will Baltimore believe it too?