Over the past week, the probability of being in South Carolina and not seeing a Republican political ad was pretty low. Counterintuitively, it’s a fact that Jerry Della Femina—legendary ad man and devout Republican—finds “sad.”

“This is a war,” he told me at his office in New York City’s Flatiron District on Wednesday morning. “And every side suffers from a war. Every side is weakened.”

On Thursday night, as the four remaining survivors of the Republican race hobbled onstage for the final debate before the primary on Saturday—reputations pummeled, egos somewhat bruised—it was clear that he had a point.

“Obama couldn’t hurt these guys anywhere near as much as they’re hurting each other,” he said lugubriously. “They’re basically doing his job. They will eventually get him reelected.”

“I remember when the Democrats were running against each other—Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, Joe Biden, Barack Obama—they didn’t do this. They didn’t have this kind of advertising against each other. What it says is—and I say this as a Republican—is that Democrats are smarter than Republicans when it comes to getting elected.”

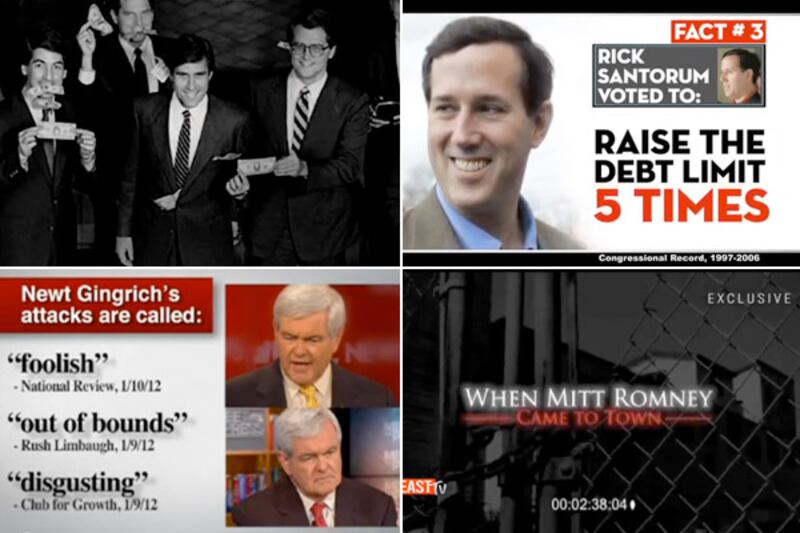

We looked at some of the attacks ads that are currently flooding South Carolina’s airwaves—the anti-Newt, the anti-Santorum, and inevitably, the anti-Bain.

Della Femina’s critique was decisive: “I think these ads are particularly good.” He spoke with the authority you’d expect from someone whose time in agencies served as the inspiration for the hit television series Mad Men. “Sad to say, negative advertising really works.”

After being in the industry for almost 50 years and having run one of the most successful shops in the country, Della Femina knows effective advertising when he sees it.

The commercials that made a particularly strong impression were those edited from the 30-minute video that attacked Romney’s work at Bain Capital. “I’ve never heard so many Southern accents. I’ve never seen so many fat people. This is amazing. I guess someone sat back and said, ‘We’re aiming at fat people with Southern accents.’ They talk about how Bain and Romney took their jobs away and changed their lives. If they set out to say, ‘How can we get Obama reelected?’ this is what they would’ve come up with.”

He went on to speculate: “Does Obama offer to buy these anti-Bain commercials and run them for himself? It’d be a funny thought if he went to these groups and said, ‘Hey, let me buy your commercials and I’ll show them to the country instead of just South Carolina.’”

For Della Femina, the prospect of four more years of Obama in the White House is not something he’s “looking forward to.”

He feels that Obama has “a weak record. He’s made some pretty serious mistakes. His agenda may be a little bit more socialistic than we’ve ever been. He’s right up there with Carter for not having done his job. I don’t think he’s been a good president. That said, I was a Huntsman person to begin with. He certainly didn’t make a big splash. He wasn’t strong enough for anyone to attack.”

As for Gingrich, Della Femina finds him “creepy”—not a candidate that he could vote for. However, Romney, he later revealed, is a candidate he “could live with.”

My next question was obvious. If Romney won the Republican nomination, would Della Femina consider working for the campaign? Although he has spent the majority of his career selling consumer products, his former agency, Della Femina Travisano & Partners, was part of the team that created the campaign to elect Ronald Reagan in 1984.

“Yes, I would work on it,” Della Femina replied unhesitatingly. But then he hurried to add that this was counter to something he had always believed: “I don’t like to work for politicians because I hate to work on anything that you can’t give back if it doesn’t work. I sell products. I do a commercial for, say, Meow Mix, and you don’t like it, you get your money back. You can return it. Politicians, you can’t return. You’re with them for four more years. And that’s scary.”

If you weren’t in the room with him, you might assume that all Della Femina was trying to do was write good copy and, perhaps, even sound clever. But if you were there, sitting beside him as I was, looking at a person who’d sold everything from tampons to toupees—with equal degrees of passion—you would have realized he was being none other than sincere. And that he really was scared.

“This election is the most important election of my lifetime and I’m an old guy,” murmured the 75-year-old toward the end of the interview. “I’ve never felt this way about an election before.”