As Michelangelo was finishing his famous sculpture David, a powerful patron appeared below the ladder on which he was standing and suggested that perhaps the nose was too thick. The artist came down and stood beside his patron to assess things. When the man looked away, Michelangelo quickly snatched a handful of dust and ascended again, pretending to tap his chisel and letting the dust slip between his fingers. Having altered nothing, he climbed down once more and waited for an opinion. The patron was delighted: “Oh, that’s much better! Now you’ve really brought it to life.”

The anecdote is a perfect parable for the power and ignorance of artistic patrons. Eager but incompetent to offer advice, Michelangelo’s patron had to be tactfully appeased. The artist’s solution was a small masterpiece in its own right: feign polite obedience, then do exactly as you please. Behind the chiseled perfection of the David lies a less savory story with more recognizably human themes: a clueless and arrogant patron outwitted by a confident and devious artist.

This is one of the tamer stories that Alexander Lee tells in his new book, The Ugly Renaissance: Sex, Greed, Violence and Depravity in an Age of Beauty. A gossipy work of muckraking history, Lee’s book unleashes all the dark spirits usually confined to the lower circles of Dante’s Inferno: brawling popes, feuding mercenaries, corrupt patrons, and sex-crazed artists. The Renaissance humanist Alberti once said that the ideal painting represents reality so perfectly that it can be mistaken for an “open window.” Lee’s book is a prose painting of Renaissance Italy with a decidedly grotesque emphasis; the sights and smells wafting through its window are invariably foul.

That Michelangelo is remembered as a sculptor and painter rather than a poet makes sense when you read lines like these:

Around my door, I find huge piles of shit since those who gorge on grapes or take a purge could find no better place to void their guts in.

It’s hardly a Sistine Chapel in verse, but the words reveal something that his most beautiful paintings conceal: 15th-century Florence was a filthy place to live. Great artists often seem vaguely incorporeal; the lofty transcendence of their work, enduring through the ages, seems incompatible with something as sordid as, well, a huge pile of shit.

But Michelangelo lived among brothels and beheadings; filth and violence defined the texture of daily life. As a young boy he was carried on his father’s shoulders to watch the public execution of several conspirators. As a young man, he boasted that he would soon become the finest painter in Florence with such arrogance that another young painter smashed his fist into Michelangelo’s face, breaking his nose.

As an adult he enjoyed drawing dirty pictures. Between sculpting his David and adorning the ceilings of the Sistine Chapel, he also found time to sketch an obscene picture of a man bending over and displaying his anus to the world. And he kept his love for bathroom poetry into old age. One of his later poems begins:

“Urine! How well I know it—drippy duct”

A fixation on the bodily is perhaps unsurprising given prevailing standards of hygiene in the Renaissance. When he was living in Rome, Michelangelo received a note of advice from his father that expressed a common attitude: “live carefully and wisely, stay moderately warm, and never wash.”

But the flaws and peccadilloes of Renaissance artists like Michelangelo pale beside the misdeeds of patrons and pontiffs. Pope Paul II, Lee notes cheerfully, “ate and drank so much that even the most flattering portraits show him as a grotesquely overweight blob.” The sexual appetites of the popes were often just as voracious. Rumors of sodomy with young boys and incest with immediate family members made the papacy seem more like the debauched court of a Roman emperor than a religious institution. The cardinals had such a bad reputation that the very term “cardinal” became an insult in Renaissance Rome.

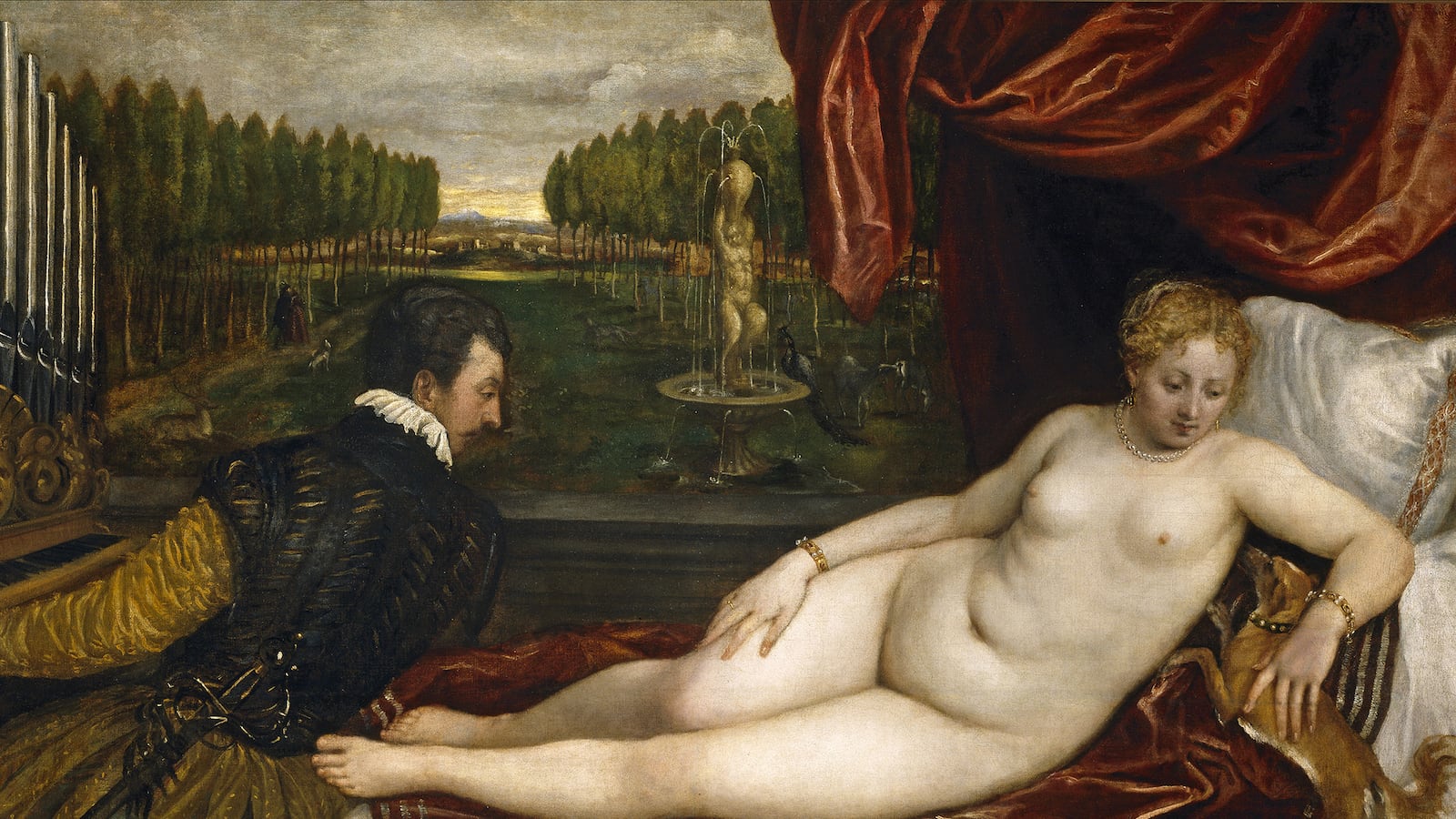

Artists were inevitably entangled with papal hypocrisy. Rafael painted dirty episodes from classical mythology in a bathroom at the Vatican Palace (sadly these are lost). And Pope Alexander VI had the painter Pinturicchio disguise his mistress as the Virgin Mary in one fresco.

Secular patrons usually behaved just as badly. Many mercenaries slaughtered their way to power, casually betraying even close family to secure their fortunes. The political volatility of Italian city-states in the Renaissance guaranteed that mercenaries could always sell their services, often starting bidding wars between rivals. Once in power, they often hired gifted artists to portray them in flattering and benevolent poses. One mercenary always insisted that only the left side of his face be visible in paintings; his right eye had been torn out in his youth.

The dirty details can be multiplied almost indefinitely, and Lee lingers over every salacious story. Though he presents far more evidence than necessary to establish his claims, his details are invariably juicy and his arguments form a refreshing counterpoint to clichés of the Renaissance as an age of beauty, tolerance, and progress.

Renaissance art was generally funded with money made in despicable ways—through warfare, the callous bankrupting of commoners, bribery, extortion, and sundry other crimes. The artworks themselves were often thinly veiled propaganda. The Medici family hired Benozzo Gozzoli to paint the fresco series Journey of the Magi to Bethlehem to help legitimize their rule over Florence. The imagery integrates Lorenzo and Cosimo Medici into biblical and sacred dramas to suggest the family’s semi-divine authority.

Lee makes a convincing case that the loveliness of much Renaissance art is inversely related to the moral ugliness of its patrons. And even the most visionary artists were subject to their patrons’ whims and bad manners. Michelangelo tricked his patron about the David, but sometimes he was forcibly reminded who paid the bills. Once he asked the pope’s permission to return to Florence for the feast of St. John before he had finished the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The pope asked when he would be finished, and he replied that he would finish as soon as he could. “I will soon make you finish it,” the pope declared, and to make his point clear, he struck Michelangelo with a staff. It may not be a story the Vatican wants told, but such nasty behavior is also a part of the Renaissance.