If you or a loved one are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. You can also call or text 988.

Before D was incarcerated in the state juvenile detention system, her mother recalled that the 12-year-old loved to hang out with her huge extended family in Waco, Texas. When she was feeling good, that might mean playing basketball. At school, even though she hated to read, she excelled at math.

“I guess she likes to count,” her mother, Tiffanie Ware, told The Daily Beast with a chuckle. “Especially if it got anything to do with money. She gon’ count that money.”

When D was struggling, Ware would let her stay at home, where she might lounge around, watching shows like Law and Order: SVU and her favorite Tyler Perry movies.

“We have a big family. So she loves to be around people. But just like when she’s irritable, then we know, you know, she don’t want to go out today, so we gon’ let her stay at home. And that’s fine. You know, she’s good. [As] long as she got food, a bed, with some covers and a TV, she’s fine.”

But the 15-year-old teenager Ware visited last month at McLennan County State Juvenile Detention Center—D is being identified only by her first initial because of her status as a minor and the possibility of her records being sealed—was spiraling.

D was sentenced in 2019 to five years in a state facility after kicking a guard who was trying to restrain her from self-harm, an act considered assault on a public officer. She had already been in and out of the juvenile justice system since age 10 after being accused of stealing and multiple alleged instances of assault, including on public officers or employees.

Since then, D has been diagnosed with myriad mental health issues as well, including major depressive disorder, conduct disorder, and “what appears to be most consistent with bipolar spectrum illness,” according to medical files obtained by The Daily Beast.

Her time at TJJD was meant to help her get better. That is, after all, what the state of Texas promises.

“While public safety and accountability are certainly considerations for youth, the juvenile correctional system emphasizes treatment and rehabilitation,” reads the agency’s website.

“Even when it is necessary to incarcerate youth, the setting is designed to be protective, not punitive,” it also declares.

But D’s mental deterioration and the “degrading” treatment her mother said she has received have devastated Ware, striking her as the opposite of what any child needs, and depriving her own girl of the second chance she believes her kid deserves.

Instead of getting help for her outbursts of violence and suicidal ideation, her mother and documents obtained by The Daily Beast suggest, the teen has endured isolation and other conditions that have exacerbated her mental-health issues. She has also faced humiliating treatment like being made to walk outside of her living area in a suicide alert gown—and being left to urinate on the floor of her cell after asking to use the restroom despite having a known medical issue causing her to have little bladder control.

Rather than a one-off, media reports and interviews with local officials and criminal justice experts show the teen’s story is emblematic of a larger fiasco in the Texas juvenile detention system.

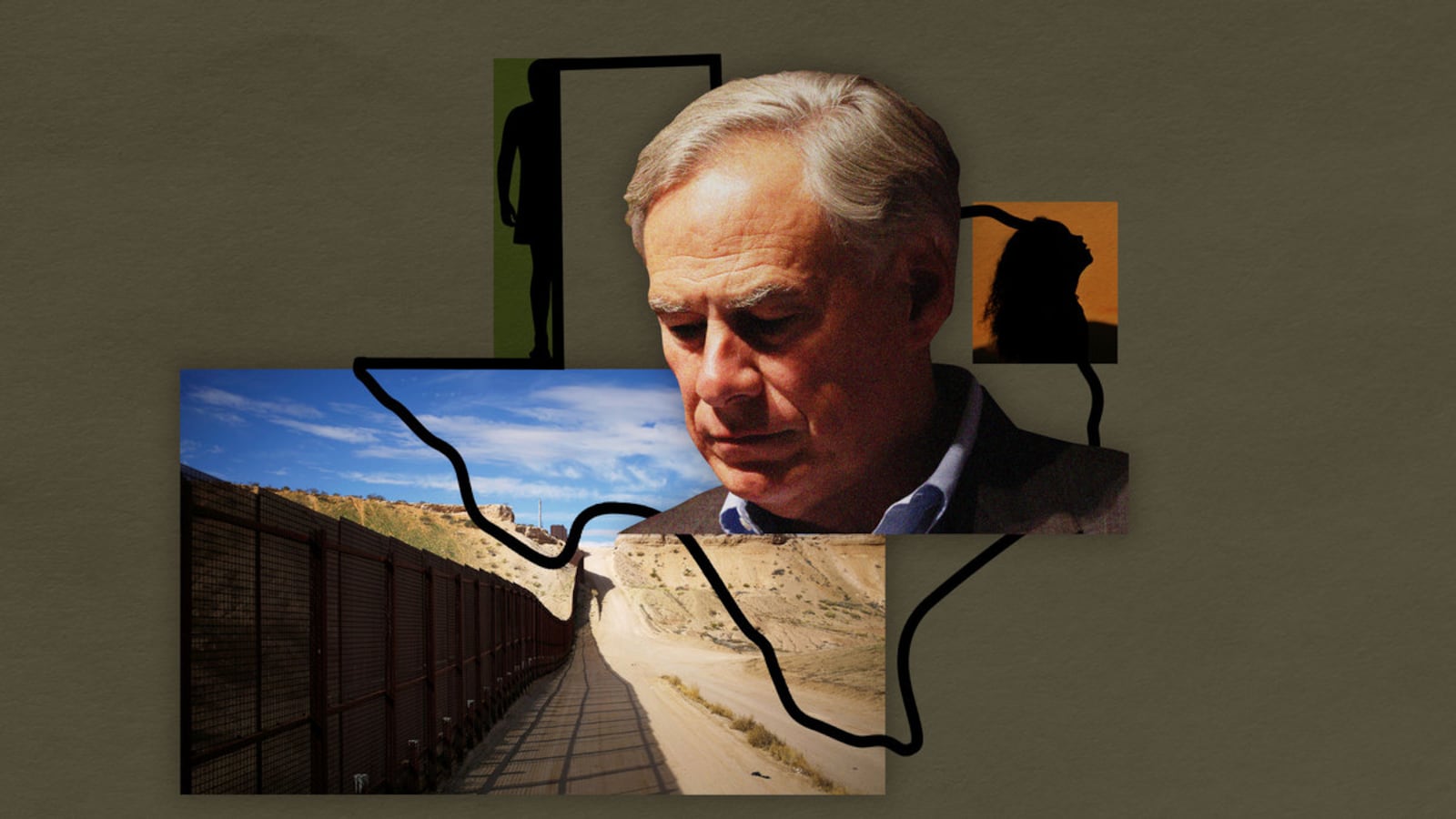

But it didn’t come out of nowhere. A long history of abuse dogs the facilities. And critics point to Gov. Greg Abbott’s budget cuts—money siphoned to his border-security projects—as well as the failure of both the governor and the GOP legislature to intervene when they argue that Texas juvenile detention centers are some of the most terrible places to be a child in America.

“It’s on him,” said Texas Representative James Talarico, a Democrat and a member of the state’s committee focused on juvenile justice. “Not that the governor needs to come up with all the solutions, but he is the only one that can actually bring the right people together, the state lawmakers democratically elected across the state, bring us together to solve this problem once and for all.”

Baby “D” with her mother.

Courtesy Tiffanie WareIn a statement, Abbott’s press secretary, Renae Eze, insisted the safety and security of staff and youth at these facilities were a “top priority” for the governor, and denied any negative impact on the agency from his budget moves. She also argued the governor was committed to reform and greater transparency, that funds were being or had already been restored in some cases, and that Abbott backed raising salaries to improve staffing—albeit during the next legislative session in 2023.

What is not in dispute is that the roughly 550 children confined in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department’s five state secure facilities are facing a crisis. As first reported by the Texas Tribune, nearly half of the kids incarcerated have been on suicide watch. And ombudsman reports have shown that the children stab themselves with springs and even insert objects into their urethras just for relief from intense isolation—after sometimes being left in their cells for up to 23 hours a day.

Due to “catastrophic” staffing losses, kids have also been asked to urinate in bottles when there are not enough guards to take them to the restroom. This has led department heads to publicly discuss fears of completed suicide attempts and nearly completely halt intake from county facilities to manage spiraling staff-to-youth ratios.

“TJJD does not condone long hours of confinement for youth,” agency spokesperson Barbara Kessler told The Daily Beast, adding that the agency has tried to address incidents like this by sending “roving teams” to help kids in understaffed areas take care of “basic needs.”

In July, when Ware went to visit her daughter, she said D was wearing virtually nothing but a suicide alert gown—a thick cloth frock meant to limit a person’s ability to self harm. She told her mother, through tears, that she had been isolated as such for 48 hours.

Kessler wrote The Daily Beast that the gowns are provided to children “only while significant risk is present,” and that “youth are offered suicide resistant underwear whenever a gown is offered.”

While medical records show that D has severe issues with self-harm, she told her mother that both the confinement and her inability to leave for a bathroom break have pushed her to further suicide attempts. And when guards grab her to stop her self-harm, she reacts and fights back—causing her to become more entrenched in the system.

<p><em><strong>Know something we should about injustice? Reach out to Eileen Grench at Eileen.Grench@TheDailyBeast.com or securely at eileen.grench@protonmail.com.</em></strong></p>

When she was initially admitted into Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex, a mental health specialist said D would benefit from a first stop at their Mental Health Treatment Program, according to internal agency documents provided by her mother. But that didn’t happen, due to a lack of room in the program.

Kessler told The Daily Beast, “TJJD cannot address the specifics of a youth’s case because confidentiality laws protect the youth in our care from any public disclosure about their status or case.”

Now, D herself wants to be sent to a hospital for care—something her mother is fighting for, as well.

“Trust me, I may not be crying now. But I’ve cried. I prayed and I’ve cried and I’ve prayed. I mean, it just hurts me that as a parent, it took all of this…. She didn’t have to use the restroom on herself for somebody to actually answer the call to try to help her and these other kids that may be going through the same issues,” said Ware.

“I’m saying it’s sad that as a… as a community, or as the people of God, you know—honestly, it’s got to be something done,” she added.

In Texas, as across the country, the burden of the crisis has fallen most of all on youth of color.

In the Lonestar State, Black kids like D are 4.7 times more likely to be incarcerated than white children, according to an analysis by the nonprofit No Kids in Prison, making up nearly 35 percent of incarcerated children. Black children only account for about 12 percent of the state’s population of kids overall.

And studies suggest that Black children with mental health issues are also more likely to be referred to the juvenile justice system than their white counterparts—and less likely to receive medication.

While white children account for 34 percent of the state’s youth, they only make up 19 percent of the incarcerated population.

Over the years, the system’s children have faced multiple cycles of crisis and reform. Following a complaint filed by local youth advocates Texas Appleseed and Disability Rights Texas alleging physical and sexual abuse, the U.S. Department of Justice is once again investigating a pattern of sexual abuse at the facilities, a redux of a similar investigation in 2017.

Since a sex abuse scandal that year, the number of youth at TJJD facilities has fallen significantly. But as reported by the Houston Chronicle, problems with staffing and violence continued through to the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. At TJJD’s Gainesville State School, youth rioted for six days in 2019, prompting a failed attempt by lawmakers to close the facility.

Since the pandemic, staffing issues at the system’s rural locations have gone from serious to being described as “catastrophic” by the agency’s own leader, interim TJJD Director Shandra Carter. This has led to a breakdown of the department’s ability to safely maintain programs meant to help rehabilitate and stabilize young prisoners.

“The risk that we are most concerned about is a serious assault of a staff, serious assault of a youth, or a potential completed suicide,” she said at a recent hearing of the Texas Juvenile Justice & Family Issues Committee.

As of that hearing on Aug. 9, she said that not even half of correction-officer positions were actively staffed. And there were 50 percent and 25 percent vacancy rates for case managers and educators, respectively. The correctional officer turnover rate stands at roughly 70 percent.

“Since TJJD’s creation, the agency has been caught in a seemingly endless cycle of crises and instability, even after legislative initiatives cut in half the number of youth it must directly supervise and facilities it must operate,” read a May report by the state Sunset Commission, charged with reviewing whether agencies should continue to exist.

In the report, the commission recommended giving the agency’s oversight ombudsman more authority and called for the state legislature to increase TJJD’s appropriation to “stabilize staffing levels”.

“In some areas, we were literally competing with Buck-ee’s,” Carter told lawmakers, referring to the popular gas station chain—despite a 15 percent increase in salary.

To add insult to injury, in 2020, Gov. Greg Abbott instituted a 5 percent budget cut on the agency. The foster care and adult prison systems were exempt from this same belt-tightening. Last year, Carter’s predecessor, Camille Cain, abruptly quit the agency the day after the governor siphoned $30 million in funding from the agency to “Operation Lonestar.” The latter gambit has deployed thousands of personnel and billions of dollars to the border under the auspices of targeting criminals who try to enter the United States.

The governor’s spokesperson pushed back hard on the idea that immigration crackdowns had directly dented the budget for juvenile detention. “It did not impact the agency’s operational budget in any way and is not related to any operational decisions made by TJJD,” said Eze, who added, “Many private and public employers like TJJD are currently having a difficult time finding employees.”

Talarico disagreed. Resulting cuts to programs shown to rehabilitate and prevent further involvement in the justice system “should drive taxpayers of all political parties crazy,” he told The Daily Beast.

“Greg Abbott is obviously a Republican governor, and his party controls both branches of the legislature and controls every agency in the state,” he added.

“And so when the governor wants to move funding from a critical agency, like the Juvenile Justice Department, to fund a stunt on the border, there’s no pushback, there’s no accountability, there’s no investigating, you know. Money is just moved at a whim based on the governor's political needs. “

Even in a mass incarceration hot spot like the United States, where stories of death and suffering behind bars are rife, experts say the situation facing troubled Texas kids is uniquely horrifying. But the nightmare in Texas state facilities for kids are just a disturbing piece of a larger national crisis, as the Marshall Project reported.

“What’s happening in Texas feels, to me, very extreme, but all too common [a] phenomenon,” said Dr. Ryan Shanahan, a research director with the Vera Institute for Justice, an advocacy and policy clearinghouse for justice reform. “What hit the hardest was that if any parent was treating children this way, they would have their families ripped apart, they would face criminal prosecution.”

Shanahan previously headed up the Vera Institute’s juvenile justice department and now focuses on young adult confinement.

Advocates, Talarico, and even Carter herself have expressed hope that the crisis means they can begin looking to the promise of smaller facilities, where both staff and kids can feel safer. And that the attention paid to the centers will offer the opportunity to reimagine justice for the state’s most vulnerable children. Both ambitions are shared by reformers nationwide.

The problem is no one seems to be listening.

In a letter to Gov. Abbott, Talarico and 33 other Democratic lawmakers beseeched the governor to call a special session to solve what he called “state-sponsored child abuse” at the centers. But so far, the governor has not replied, according to Talarico.

“The agency is developing their budget request for next session, and the governor will support their request to increase the salaries needed to hire and retain a qualified workforce,” the Abbott spokesperson wrote The Daily Beast. The next legislative session is due in 2023.

But many local and national advocates argue that additional cash won’t necessarily fix TJJD’s issues.

Juvenile justice expert Vincent Schiraldi, of the Justice Lab at Columbia University —who himself was called in last year for six months to tackle the crisis at New York City’s Rikers Island jail—said the goal should be to release kids, not add more staff.

Texas’ issues, Schiraldi told The Daily Beast, are extreme. D’s treatment, he said, is not what “better systems” would do.

“When was the last time you were unable to get out of a room to use a bathroom so you urinated on yourself?” he asked. “That’s incredibly humiliating for a child, and then to put them in a suicide gown on top of that, because you’re understaffed, is compounding that humiliation. She’s a young child who’s been locked up since she was 12, and she’s got mental-health issues. And on top of that, she’s locked in for [up to 23] hours a day in a gown. And has to periodically urinate on herself. You can imagine what you’re doing to an already fragile kid.”

TJJD’s spokesperson insisted to The Daily Beast that the agency is ”working with legislators on how to effectively modernize and adopt best practices that work for Texas. This includes expanding services to youth who can be served closer to home and increasing wraparound services to our juvenile probation partners in the communities.”

But for Ware, what matters most is that her daughter be housed in a hospital, not a jail. In October, when she turns 16, her mother says, D is facing transfer to an adult prison.

“If, you know, they don’t let her come home, my hope is that they at least get her into a hospital that she can be cared for and that she can get her right medications,” the mother told The Daily Beast. “And that she’s getting the right therapy that she’s supposed to have as, you know, as a child and also as a mental-health person,” she said.

“And that she’s not locked up. You know what I’m saying? She’s not bound to chains and all that, because I honestly, I just—it just breaks my heart not just for my child but to see other kids going through the same thing.”