Dr. Bill Nolte and I have something in common. Neither of us has read Dear Martin, a widely praised YA novel by Nic Stone. This did not stop Nolte, in his capacity as school superintendent of Haywood County, North Carolina, from yanking Dear Martin from a 10th-grade class curriculum after one parent complained. That’s right, one parent.

That dad, Tim Reeves, shown here airing his objections at a Haywood school board meeting, objected to his son being exposed to the novel’s profanity and sexual allusions. I do not question his sincerity or his right to lodge a complaint. I do question his gullibility as a dad. As someone who was once a North Carolina teen, I know the first thing I would do if I wanted to wriggle out of reading a book for homework: I’d go home and complain to my folks about cuss words and sex.

But Reeves’ possible shortcomings as a father don’t bother me nearly so much as that school superintendent’s behavior. To cave like that when just one irate parent walks through the door? To pull a book without, as he admitted, having consulted with the school’s principal or the teachers involved, or having read the book? Talk about not doing your homework.

This is not the first time Dear Martin has been yanked from a school, and it is certainly not the only book to endure such condemnation. Last week’s book bonfire star was Maus, Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer-prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust. In that case, the cries of the McMinn County, Tennessee, parents appalled by the cussing and the sex seemed especially ludicrous since the book’s protagonists are mice and its villains are cats and pigs. Not so long ago we were hearing that today’s young people are so sensitive as to require trigger warnings on any book even possibly upsetting, but it sure seems now like it’s the parents, not the kids, who need coddling.

Not to pick on Southern school systems—there have been recent cases of schools from New Jersey to California banning Huckleberry Finn (a venerable target, having been the subject of bans at least since 1885, when the Concord, Massachusetts, library deemed it “trash” unsuitable for the shelves). And To Kill a Mockingbird and The Bluest Eye still make the American Library Association’s Most Banned Books List with depressing regularity.

The bad news is that lately there seem to be more and more efforts to get rid of books that somebody somewhere finds offensive. The good news is that it doesn’t seem to work too well. Since those folks in Tennessee threw their hissy fit over Maus, it’s shot to the top of the bestseller list.

Which suggests to me a slightly counterintuitive conclusion: Maybe we should encourage the book-banning. After all, nothing speaks to a teenager’s sense of rebellion like being told not to do something. “Don’t you dare read [Maus, Dear Martin, Huck Finn, etc.]” would almost surely gain for any title a readership far larger than the most idealistic English teacher could dream of.

With that in mind, I remember one of the most depressing moments of parenthood for me was scanning a list of recommended summer reading handed out to my children when they were in middle school. On that “enlightened” list were all the books that my boomer generation read on our own as teenagers, such as Slaughterhouse Five and Catch-22, books that no public school in the ’60s would have let in the door. Nice going, I remember thinking about those well-meaning educators, you just took all the illicit fun out of reading a whole shelf of good books. Because nothing kills desire in the mind of a teenager like respectability.

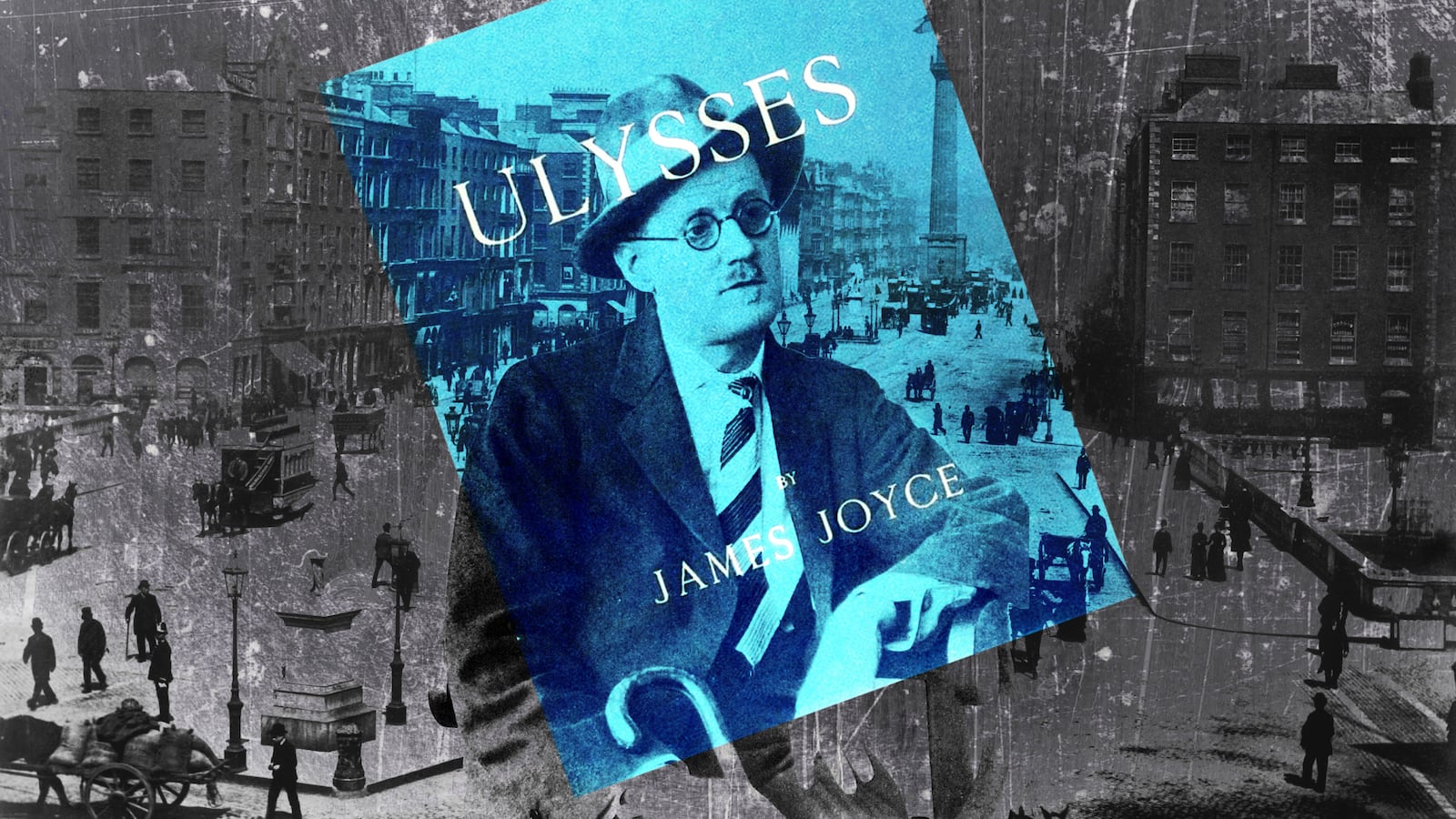

And that brings me to the granddaddy of “dirty” books, which turns 100 today.

On the morning of February 2, 1922, in accordance with the wishes of its author, Ulysses was officially published when the publisher, a Parisian bookseller, received the first three copies from the printer. It was also the author James Joyce’s fortieth birthday.

Ulysses was deemed obscene even before it was published in full, when Joyce was serializing parts of it in little literary magazines, and it ran afoul of censors both before and after it was finally published in book form. Things came to a head in 1933 when Random House wanted to publish an American edition. In one of the most enlightened and perceptive decisions ever delivered in a courtroom, Judge John Woolsey decreed that Ulysses was not obscene because, for one thing, while it dealt with sexual matters, its aim was not to titillate, or as he put it, “whilst in many places the effect of Ulysses on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac,” and, “in spite of its unusual frankness, I do not detect anywhere the leer of the sensualist. I hold, therefore, that it is not pornographic.”

Woolsey is talking about the author’s intent, a subject that all those parents and school administrators so eager to ban Maus, Dear Martin, or even Huck Finn would do well to consider. When Mark Twain drops the N-word, for example, it should be clear, if you’re paying attention, that he hates the word as much as anyone could. They might also ponder another passage in Woolsey’s decision, which may be the greatest “get over yourself” rant ever written:

“The words which are criticized as dirty are old Saxon words known to almost all men and, I venture, to many women, and are such words as would be naturally and habitually used, I believe, by the types of folk whose life, physical and mental, Joyce is seeking to describe. In respect of the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds of his characters, it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic and his season spring.”

But that was long ago, when Ulysses was young and disreputable. “Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough,” says Noah Cross in Chinatown. He might have added “and great controversial fiction.”

Happy birthday, Ulysses.