Before Mitzi Perdue’s engagement ring sat in a case at Sotheby’s, it sat on the bottom of the ocean floor. For 363 years.

Perdue, a hotel heiress and widow of millionaire chicken magnate Frank Perdue, is auctioning off her 6.25-carat, step-cut emerald engagement ring to benefit the fight against human trafficking in Ukraine. It is expected to raise between $50,000-$70,000.

For the first time, she is also sharing the ring’s fascinating backstory—one that spans continents, centuries, and several different chicken farmers—and the story of her husband’s relentless, 16-year search for the ship that carried it.

“As far as I can tell his motivation was the romance of treasure hunting,” Mitzi told The Daily Beast. “How often does a normal mortal have a chance to hold history in his or her hands?”

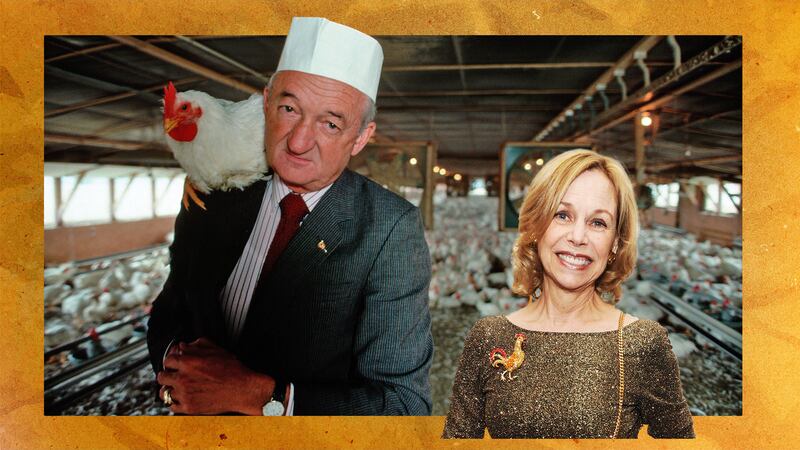

Frank Perdue’s family business was the USA’s third-largest chicken processor. His widow, Mitzi (shown here in 2010), is auctioning off an emerald ring Perdue gave her from a treasure trove off the Florida Keys.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Sotheby’sThe story starts in 1622 in Havana, Cuba, when the Nuestra Señora de Atocha set sail for Spain. Named for a holy shrine in Madrid, the ship was part of a fleet sailing back to Seville with riches acquired from various Spanish ports in South America. The Atocha alone carried 47 tons of gold and silver, according to The Washington Post, as well as jewels, indigo, and 20 bronze cannons meant to protect the slower ships in the fleet from plunder. The value of its cargo has been estimated at up to $500 million.

But two days after the Atocha set sail, tragedy struck. A massive Atlantic hurricane flung the ship into a coral reef outside the Florida Keys, tearing it apart and plunging it 55 feet under the water. Of the 265 people onboard, only five survived. The Spanish crown sent crews to recover the ship for years, to no avail.

Instead, the ship stayed buried under the water, rumored about but never recovered—until nearly 400 years later, when a chicken farmer named Mel Fisher set out to find it.

Fisher, a colorful character who later in life became known for carrying a conch-topped scepter around town, first learned of the Atocha while running a diving shop in California. He had recently given up a job on his family’s chicken ranch in Indiana to pursue his dream of deep-sea diving, and was intrigued when a customer told him about the treasures hidden off the coast of Florida. He relocated his entire family to the state in 1962 and, several years later, moved to Key West to start searching for his white whale: the Atocha.

It was around this time that Frank Perdue, too, learned of the treasure. By that time, Perdue was a successful businessman, having turned his family’s backyard egg business into the third-largest chicken processor in the country. He was widely regarded as a trailblazer for his streamlined processing practices—many of which were reviled by animal rights groups—and as a marketing whiz for his homey, personable ads. (His tagline, “It takes a tough man to raise a tender chicken,” helped make the company a household name.)

But according to his wife, he was also a man of varied, occasionally obsessive interests. After becoming interested in the Founding Fathers, she recalled, he not only read every biography of them he could find, but also visited the countries where Thomas Jefferson and John Adams served as ambassadors and traveled to the West Indies to see the birthplace of Alexander Hamilton. (While visiting the Alexander Hamilton Museum in Nevis, Mitzi recalled, her husband wound up leading his own tour after proving he knew more than the guide.)

So it was not surprising that when Perdue’s good friend Melvin Joseph told him about the Atocha treasure, he became obsessed with that, too.

Joseph, the founder of a prominent Delaware construction business, was an early investor in Mel Fisher’s treasure-hunting business, Treasure Salvors Inc. According to Joseph’s daughter, Virginia Kauffman, the men met while Joseph was working on a road construction project in Daytona Beach. The businessman was leery of the project, Kauffman said, until he visited Key West and saw Fisher’s operation for himself. After that, she said, “we paid the electric bill, we paid everything.”

When Joseph told Perdue about the treasure-seeking operation, the chicken magnate eagerly chipped in, too.

The two friends were far from casual investors. Perdue had a shelf full of books on the shipwreck, Mitzi says, and would talk endlessly to anyone who asked about its tragic history. Kauffman recalled her father flying Perdue down on his private plane several times to visit the search site and meet Fisher in person—as two veterans of the chicken industry, they had a lot to talk about. Fisher’s son, Kim, told The Daily Beast he remembered meeting Perdue in his father’s office as a teenager.

“He believed in my dad’s dream—the fun and romance of adventure, of searching for and finding treasure,” Fisher said.

“That’s why Frank got into it,” he added. “Because it’s fun. He didn’t need money or anything.”

In those early days, in fact, it seemed the money might never come. Fisher, who was famous for starting each morning by yelling “Today’s the day!” spent more than a year searching near the Matecumbe Keys before a Ph.D. candidate found documents in the Spanish archives that suggested he was looking in the wrong place. The report placed the Atocha near the Marquesas islands, some 35 miles off of Key West. Once there, the crew was misdirected yet again by a few silver bars they found five miles to the northwest. “I wished we had never found them,” Bleth McHaley, the vice president of Fisher’s company, later told The New York Times. “It was a false lead that cost us years.”

Mel Fisher—surrounded by members of his company, Treasure Salvors Inc.—raises a glass in Key West, Fla., July 21, 1985. The treasure Fisher found was valued as high as $400 million in silver bars, gold bullion, pieces of eight, copper ingots, as well as the unrecorded wealth carried by the 289 people aboard the galleon Nuestra Senora de Atocha, which sank in a hurricane in September 1622.

AP Photo/Joe SkipperThe company also had to fight off lawsuits from both the state of Florida and the U.S. government, each of which claimed they were entitled to some of the ship’s riches. (The Supreme Court gave 100 percent of the proceeds to Fisher’s company in the Florida suit; the U.S. government lost in the Fifth Circuit of Appeals.) The search also extracted a personal cost from Fisher: His son, Dirk, and his wife died in 1975 after a search boat they were using capsized and trapped them underwater. A diver, Rick Gage, was also killed. "Notwithstanding the deaths,” Fisher later told Time, “it was worth it."

In 1985, after 16 years of searching and millions of dollars spent, Fisher’s team finally struck gold—40 tons of it, to be exact. Divers working 54 feet underwater located hundreds of 70-pound silver bars, alongside an actual treasure chest filled with gold coins and jewels. The rest of the loot was not far behind. According to the Dayton Daily News, Fisher was on the shore at the time, so his 26-year-old son Kane grabbed the radio and screamed: “Put away the charts! We’ve hit the main pile!”

The discovery was one of the largest sunken treasures ever discovered. By the next year, the ship had yielded more than 3,000 emeralds, according to a Los Angeles Times article from the time, and was expected to produce even more. Divers also unearthed an intricately engraved gold cup, 40 to 50 feet of gold chain, and an emerald-studded bracelet shaped like a snake biting its tail. A single gold-and-enamel spoon from the ship was said to be worth up to $180,000.

The scene in Key West after the discovery was nothing short of a gold rush. Perdue and Joseph were some of the first investors on the ground, accompanied by a crowd of rubberneckers and a few would-be thieves. (Fisher installed underwater cameras and hired armed diver-guards to protect the treasure from looters.) The ship’s bounty was divided between Fisher and his 180 investors, many of whom were made millionaires by the discovery. “I’m going to pay off my mortgage,” one giddy investor told United Press International at the time.

Perdue and Joseph, however, chose to donate the vast majority of their haul. Some of it went to museums like the Smithsonian, some to colleges like Delaware Technical Community College. In 2007, the sale of 2,700 silver coins they donated to the college raised more than $700,000 for the Melvin Joseph-Frank Perdue Memorial Endowment. Perdue, Mitzi says, was “the most philanthropic person I ever met.”

A cannon, gold chalice, and gold spoon discovered on board the Nuestra Señora de Atoche.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/ Don Emmert/AFP via Getty ImagesBut there was one piece of treasure Perdue kept for himself: a 2-inch, 6.25-karat octagonal emerald. According to Kim Fisher, who now runs the family business, the emerald was one of 70 pounds of emeralds smuggled onto the ship from the Muzo mine in Colombia, now known as the emerald capital of the world. The emeralds were never listed on the ship’s manifest; the only reason Fisher knows of their existence is because of a letter the smuggler wrote to his brother, bragging about them. So far, they’ve only managed to recover about six pounds from the wreck. “I’ve got two boats out there looking for the rest of them now,” Fisher said Friday. “I’m waiting for them to call me.”

When Perdue received the emerald—the result of a computer process that evenly divided the loot between investors— he sent it to master gem cutter Reginald C. Miller to expertly remove and set it in a simple gold band. Then it sat, for years, in a vault—until Perdue met a striking divorcée named Mitzi Henderson at a party in 1988.

Mitzi was the daughter of Sheraton Hotels co-founder Ernest Henderson and partial inheritor of his stake in the company. At the time, she had fled her East Coast upbringing and was working as a rice grower and writing an environmental column. Both she and Perdue had vowed never to wed again, she says, but they hit it off instantly. She lived in California and he in Maryland, but they talked every day on the phone for hours. Six weeks later, when she came to visit him for the first time, he pulled out the emerald ring and proposed.

“There are no words to describe [how I felt]” Mitzi says of that moment. “Overwhelmed, amazed, joyous.”

“If you want to impress a girl, that’s the way,” she added with a laugh.

Perdue and Mitzi were married 17 years, until he died in 2005. Though she stopped wearing the ring after his death, Mitzi says, she never felt called to give it away—until now.

Last spring, Mitzi traveled to Kyiv to meet with Andrii Nebytov, the police chief of the Kyiv region, as part of her philanthropic work on human trafficking. Overwhelmed by what she saw there, Mitzi says, she returned committed to contributing to the cause in some way. Rather than asking her rich friends to divert money from their existing philanthropic causes, she decided to create a funding stream of her own by auctioning the emerald at Sotheby's on Dec. 7. The proceeds will go to Silent Bridge, an organization that fights human trafficking in Ukraine and Nepal.

Giving up the ring is bittersweet, Mitzi admits. It is beautiful—a piece of history—and it reminds her of Frank. But, she said, “if you weigh the good that it could do versus the pleasure of holding it in my hand, I’ll take the good it could do.”

Plus, she knows it’s what her late husband would have wanted: “Since I know that Frank gave most of what he got from being a financial backer [of the Atocha hunt] to charity,” she said, “I just know that he would endorse doing this.”

Joseph and Fisher, Perdue’s partners in the treasure hunt, are also long since dead—according to Kauffman, Joseph died on the day Perdue was set to be buried. But a quote from Fisher’s daughter, Taffi Fisher-Abt, suggests he might be just fine with the ring changing hands, too.

“My father always told me, ‘These treasures used to belong to somebody, and we are their custodians now, and someday they’ll belong to someone else,’” she said in 2015, according to The New Yorker. “‘Then those people will be gone, too, but the treasures will remain. People disappear, but gold shines forever.’”

Or in this case, maybe emeralds.