Just one year ago, while U.S. national security experts were growing increasingly concerned Russia would unleash a military onslaught against Ukraine, most Americans (as well as many people around the world and even in Ukraine) had no idea a huge escalation of Russia’s long war against its neighbor was around the corner.

Few would have guessed that one year later, not only would have Russia commenced its operation but that Ukraine would have repeatedly repulsed the invaders, America would have led the world in support for Kyiv, more than $100 billion in aid would have been committed to support Ukraine’s defense of its land and people, and that NATO would emerge stronger (and very likely larger) as a result of Putin’s gross miscalculation.

For this reason, as we look ahead to 2023, humility is in order. Indeed, the true sign of foreign policy expertise is knowing how much you do not know. But that should not and must not stop us from assessing looming risks so that we may both prepare for them and seek to defuse them.

Each year at this time, events and reports are produced that seek to identify trends and anticipate flashpoints for the year ahead. Taken together, the assessments for 2023 are deeply unsettling.

A late November report from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) begins by noting that, “There are more than 100 armed conflicts in the world today. The suffering caused by these conflicts, combined with climate shocks and rising food and energy prices will make 2023 a year of vast humanitarian need.” (Also worth exploring is the Geneva Academy website, which currently identifies 110 armed conflicts in the world—including more than 45 in the Mideast and North Africa, more than 35 in the rest of Africa, 21 in Asia, seven in Europe and six in Latin America.)

The report from the ICRC cites countries and regions in which the pain is likely to be particularly acute. These include Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Yemen, Ethiopia, Syria, the Sahel, Haiti, and Ukraine. Many of these places recur in other such lists. The International Rescue Committee’s list of “the top 10 crises the world can’t ignore in 2023” is topped by the ongoing human disasters in Somalia and Ethiopia. Also on its list are Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, Burkina Faso, Haiti and Ukraine. Poverty, drought, failed efforts at diplomacy, endemic violence, terrorism and war all factor into the projected suffering for the people of these regions.

Looking at the underlying trends driving many of these conflicts and other areas of concern for policymakers, the Council on Foreign Relations recent piece “Visualizing 2023: Trends to Watch” provides useful context. It includes snapshot analyses of global and regional drivers of events like food price inflation, China’s military build-up in the Asia-Pacific region, shifting relations between India and Russia, a brain drain in Nigeria, and deepening political divides in the U.S.

The Economist does an annual outlook edition, and within it can be found deeper dives into particular regions. One that caught my eye (because it jibes with my sense of issues that deserve to be watched) was a look at Asia by Dominic Ziegler, which asserted “the coming year will be the next iteration of a great global struggle in Asia.” Specifically, it expressed concerns about growing tensions around Taiwan and in the South China Sea, and the seemingly ever-present risks associated with North Korea, as well as border disputes in the Himalayas between China and India.

Other recent assessments worth reviewing take a more U.S. centric perspective, exploring how the evolving global situation impacts U.S. interests—and may command the attention of U.S. policymakers.

For Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Tony Cordesman, emeritus chair in strategy, has produced “A World in Crisis: The Winter Wars of 2022-2023.” The CSIS evaluation identifies wars that are “violent or nonviolent that are on-going in the winter of 2020-2023 and that seem likely to continue to affect global security in the future.” These include what they identify as “winter wars” in Ukraine—between the West and Russia on economic and political issues, another contest between the West and Russia on military preparedness, one on nuclear forces and deterrence, one on precision and emerging weapons technologies, one concerning “going from cooperation and competition with China to confrontation and active war planning,” one in the Middle East, another in the Koreas, another pertaining to proxy and “grey area” conflicts, and finally one pertaining to fragile, divided, authoritarian and undeveloped states.”

To add another list to these, pertaining to the flashpoints I think are most likely to demand the attention of U.S. policymakers (which is not to say they are the ones that are most important, have the greatest human cost or the ones to which we ought to devote more attention), let me offer another “top 10.”

It is my view, cognizant of the risks cited in these other reports and the demands on senior officials in the U.S. government, that the following issues are the flashpoints and potential flashpoints they are most likely to have to deal with in the year ahead.

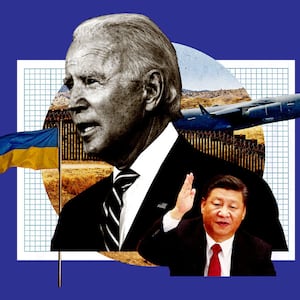

Ukraine

US President Joe Biden and President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky walk to the Oval Office of the White House on Wednesday, Dec. 21, 2022.

Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesEnsuring the U.S. provides adequate resources to Ukraine will be critical to moving the conflict toward a resolution, a goal likely to dominate attention in Kyiv, Moscow, D.C., and Brussels as the year progresses.

Some of the toughest battles may be with a Republican-controlled Congress that is resistant to offer further support. The possibility of escalation by a frustrated and defeated Russia is another area that will demand continuing attention. Further, Russia is likely to continue to use its energy leverage to penalize the West for its support for Ukraine.

Finally, expect more flareups in the Baltic region as Sweden and Finland move closer to joining NATO and Russia rattles its sabers.

Taiwan

While I don’t think it is likely China will attack Taiwan in the next several years, this will remain one of the world’s most dangerous situations.

The Chinese will continue to conduct military operations in the area. Taiwan will seek to build up its forces. The U.S. will help Taiwan.

And while a war would be catastrophic for all sides (and the global economy), it will never be far from the minds of national security specialists around the world. (Potential confrontations over other islands or sea routes the Chinese seek to control are a related area of risk.)

Domestic Violence in the U.S.

The January 6th Committee reviews footage from past hearings as it meets for its final session at the Cannon House Office Building on Capitol Hill on Dec. 19, 2022.

The Washington Post/Matt McClain for The Washington Post via Getty ImagesIncreasingly, U.S. security specialists are realizing that the greatest imminent threat to the country is the possibility of attacks and disruptions from right-wing violent extremists. That will continue to be the case in 2023, especially as legal prosecutions against former President Donald Trump and other plotters of the Jan. 6 insurrection (and other efforts to steal the 2020 election) continue and may inflame the radical fringe in U.S. politics.

Cyberattacks

Attacks from foreign governments, as well as private bad actors, have to be considered an on-going imminent threat. The fact that Russian hostility to the West is likely to grow due to its worsening situation in Ukraine (and the pressure being exerted on its economy) increases the likelihood of more serious attacks. The possibility of worsening tensions with China and volatility in Iran and North Korea also must be monitored.

Unrest in Russia, China, and Iran

All three of these countries are seeing unprecedented levels of political unrest. Should that unrest threaten the current governments, crackdowns are likely and should those crackdowns become brutal or trigger even greater unrest (as is already the case in Iran), the potential associated risks will warrant and draw immediate attention.

Israel

US President Joe Biden (R) speaks during a meeting with Israeli President Isaac Herzog in the Oval Office, on Oct. 26, 2022.

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty ImagesThe new hard-right government in Israel is likely to prove to be a headache for the Biden administration from its first days in office. While some of the problems will be largely political in nature, others will have significant security consequences.

These could include growing conflicts with Palestinians, due to the increasingly oppressive policies of the new government in Jerusalem. That government will also be seeking to fan the flames of conflict with Iran, an axis of tension that will be important to watch and try to contain. (Given Iran’s efforts to help Russia in Ukraine, the U.S. and Western appetite for penalizing them on that front—including via cyberattack, covert activity or looking the other way re: Israeli operations—might well grow.)

Africa

The conflicts in Africa have grave humanitarian consequences, yet seldom get the attention from the U.S. and the rest of the developed world that they deserve. But given that the human costs could skyrocket in the year ahead, a push for greater international intervention is, if not likely, then something that is likely to generate more discussion in international institutions like the United Nations.

Terrorism

It was never the strategic threat the Bush administration argued it was, but global terror groups remain active and likely to strike U.S. targets or our allies. Should they do that, the conversation will inevitably turn to what our response should be.

North Korea

Kim Jong Un is intent on building up his military capacity even as the people of his nation suffer. Further missile tests seem inevitable. Nuclear tests seem a real possibility. Growing tension with South Korea, Japan, and the U.S. are therefore inevitable.

Climate Change Driven Conflict

The potential for conflict and humanitarian crises caused by draught or extreme weather is growing annually. This can (and almost certainly will) produce famine, disease, refugee crises, water wars, and other forms of conflict. When these problems strike, rapid response is key to containing them. So, too, is diplomacy.

Given my earlier caveat about humility, I offer this list knowing full well that something that is not on it is likely to crop up and command the attention of our national security leadership.

That said, it is also likely every single one of the above issues will require significant resources and creative thinking if we are to protect our interests and preserve stability (such as it is) worldwide.