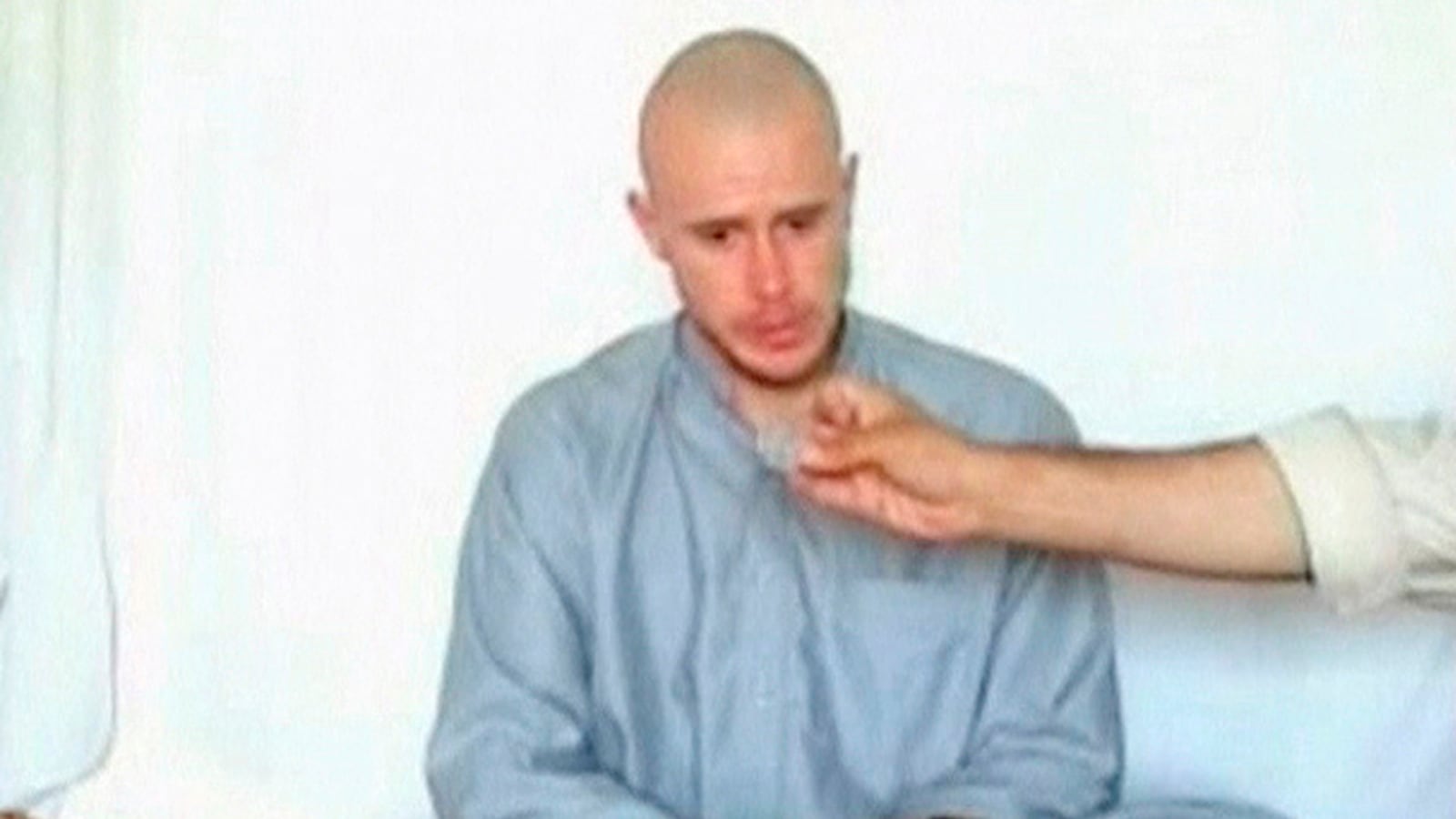

Last month, the international press revealed that the Taliban had delivered to U.S. officials a video showing that America’s only prisoner of war, Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, was still alive. What has not yet been previously reported was the U.S. government requested this proof of life as a precondition to resuming direct U.S.-Taliban talks over a prisoner swap: Bergdahl in exchange for Taliban commanders currently imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay.

White House spokesperson Caitlin Hayden declined to talk about administration contacts with the Taliban. “We cannot discuss all the details of our efforts, but there should be no doubt that we work every day—using our military, intelligence and diplomatic tools—to see Sgt. Bergdahl returned home safely,” she said.

But according to interviews with current U.S., Afghan, and Pakistani senior officials, the potential new U.S.-Taliban prisoner swap talks, which have not yet begun, are linked to a broader U.S. government effort to lay the groundwork for a potential reconciliation between the Afghan government led by Hamid Karzai and the Taliban, who he has been fighting since the beginning of the decade-long U.S. occupation. As part of the outreach effort, American officials have repeatedly asked the Pakistani government to release a captured Taliban leader. Meanwhile, semi-official talks are ongoing in Doha, Qatar, where the Taliban maintains an office that officially never opened.

“The Doha channel is still being used for contacts between the U.S. and the Taliban,” a senior Pakistani official told The Daily Beast.

Bergdahl, the only living American prisoner of war, went missing in June, 2009, when he wandered away from his base in southeastern Afghanistan, near the Pakistani border. He is believed to be held somewhere in Pakistan by the Haqqani network, a Taliban ally. Militants have revealed a total of six videos of Bergdahl in captivity, with various demands in exchange for his release. Their latest demand is that the U.S. release five senior Taliban commanders in Guatanamo who have been imprisoned there for years.

Expectations are low inside the Obama administration that the new outreach to the Taliban will have much success in bringing him home, however. In 2011 and 2012, an interagency team led by America’s Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Marc Grossman, had several direct interactions with the Taliban over the prisoner swap idea. Those talks fizzled.

Karzai was aware of the negotiations but mistrustful of any talks that didn’t go through Kabul. In the U.S. Congress, there was bipartisan opposition to any release of Guantanamo prisoners. After the negotiations were made public in early 2012 by Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the Taliban announced they were pulling out of the talks.

In the summer of 2013, the U.S. attempted another Taliban confidence building measure, the opening of a Taliban representative office in the diplomatic enclave inside Doha, Qatar. Karzai was also mistrustful of that effort and his skepticism was validated when the Taliban violated their agreement with the U.S. and raised their flag at the office’s opening, causing Karzai to have a fit and forcing the U.S. to abandon the deal to keep the Taliban office open.

Following that incident, the U.S. government maintained some level of contact with the Taliban, through both official channels and semi-official “track two” interactions. Administration sources say the current contacts with the Taliban and its allies—including the Haqqani network, which holds Bergdahl—are now managed by an interagency team led by Grossman’s successor, James Dobbins, and National Security Council senior director Jeff Eggers.

Those current interactions with the Taliban over potentially resuming prisoner swap negotiations are being conducted through the Taliban Doha office that never officially opened, but still holds senior Taliban representatives. That office sits only a few hundred feet from the U.S. Ambassador’s residence in Doha in neighborhood populated by foreign diplomatic missions.

Back in Washington, the Obama administration worked late last year to pave the way for a potential prisoner swap. Obama’s aides pushed to relax a law that previously required the Defense Secretary to certify that any prisoners released from Guantanamo would not pose an ongoing national security threat to the United States.

A small change in the Fiscal Year 2014 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which passed last December, now makes it only a requirement that the Defense Secretary notify Congress when releasing Guantanamo prisoners. That would make it easier to effect the Taliban prisoner swap, if the negotiations ever got that far.

But the administration would still face public scrutiny if it tried to send Guantanamo prisoners to live under strict supervision in Doha, as was the plan during the 2011 round of negotiations. Lawmakers are not convinced the Qatari government can be expected to keep the Taliban commanders from returning to the fight.

“With respect to Guantanamo, the President reiterated when he signed the FY14 NDAA that this administration will not transfer a detainee unless the threat the detainee may pose can be sufficiently mitigated and only when consistent with our humane treatment policy,” Hayden said.

Former officials and experts also said that the U.S. and the Taliban see the prisoner swap negotiations in a different light. For the Taliban, they have no incentive to restart peace talks with Karzai while the U.S. is withdrawing troops and the Afghan government security position is getting weaker.

“Our commitment to the political process has been so fitful and lacking any serious commitment, that on the eve of a drawdown, for the Taliban internally there’s no way the factions that favor negotiations are going to prevail,” said Michael Wahid Hanna, senior fellow at the Century Foundation. “There’s no reason for them not to say, ‘Let’s see what happens in 2014.’”

Overall, the Obama administration is aware of the difficulties of restarting direct negotiations with the Taliban, especially considering that U.S. forces were at an all-time high two years ago and are quickly going down now, further reducing pressure on the Taliban.

“The best chance we had to do this was in 2011 and 2012, but now I would put this in the ‘worth a try’ category,” one administration official said.

Karzai’s refusal to sign the Bilateral Security Agreement with the U.S., which would allow some American troops to remain in Afghanistan after this year, is also linked this effort, U.S. and Afghan officials said. Karzai’s final condition for signing the deal is that the U.S. help him establish new peace talks with Taliban, public talks that he has been discussing with the Taliban in private for months.

“Starting peace talks is a condition because we want to be confident that after the signing of the security agreement, Afghanistan will not be divided into fiefdoms,” he said last month. Karzai has also been releasing Taliban prisoners, many of whom were captured by international forces, as an incentive to persuade the Taliban to start new public peace talks.

If Karzai refuses to sign the BSA, the White House has publicly warned that that it may not be possible to wait for the next Afghan government to be seated, forcing the U.S. to leave zero troops in Afghanistan following 2014.

Karzai, whose relationship with the Obama administration is at an all-time low, is also asking the United States to place pressure on Pakistan to make concessions to the Afghan Taliban, including by releasing Taliban leader Mullah Baradar, the former deputy leader of the militant group, whom the Pakistani’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) captured in 2010 and partially released into house arrest last year.

The U.S. has complied with Karzai’s request, according to a senior Pakstani official, who said that the Obama administration has repeatedly pressed Islamabad to release Baradar. The Pakistani government has so far rejected the requests, saying it does not believe that Baradar has influence enough to bring the Afghan Taliban into peace talks, following his three years in prison.

“The problem is that Karzai expects that if he gets hold of Mullah Baradar that he can use him. But Mullah Baradar according to our sources is relevant only if he does what the Taliban tells him to do. If the Taliban tell him not to talk, then what is the point?” the Pakistan official said.

The senior Pakistani official also denied reports that the ISI had drugged Baradar to keep him from talking substantively with Afghan government officials who visited him recently.

“The Taliban didn’t want him to talk, so he didn’t talk,” the official said. “If the Taliban doesn’t want to talk to Karzai, the Afghans can’t use Mullah Baradar as a back door, although that’s what they are trying to do.”

Shuja Nawaz, director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, said that the Pakistani government hasn’t yet decided that Afghan reconciliation is in Pakistan’s interest and the Pakistanis are also reluctant to help because they don’t want their own lack of influence over the Taliban to be made public.

“In the past the Pakistani intelligence services claimed much more control over their contacts in Afghanistan. By now they are much more realistic about the reality of the situation,” he said.

Without a thaw in his relations with the Taliban, Karzai is unlikely to ever sign the BSA, said Nawaz, because he doesn’t want that to be his final substantive act as he leaves more than a decade in office.

“Karzai has this vision of himself not being one of those past leaders of Afghanistan who ceded to foreign powers and he sees the BSA in that context,” said Nawaz. “Also, the moment he signs it, he’s a lame duck.”