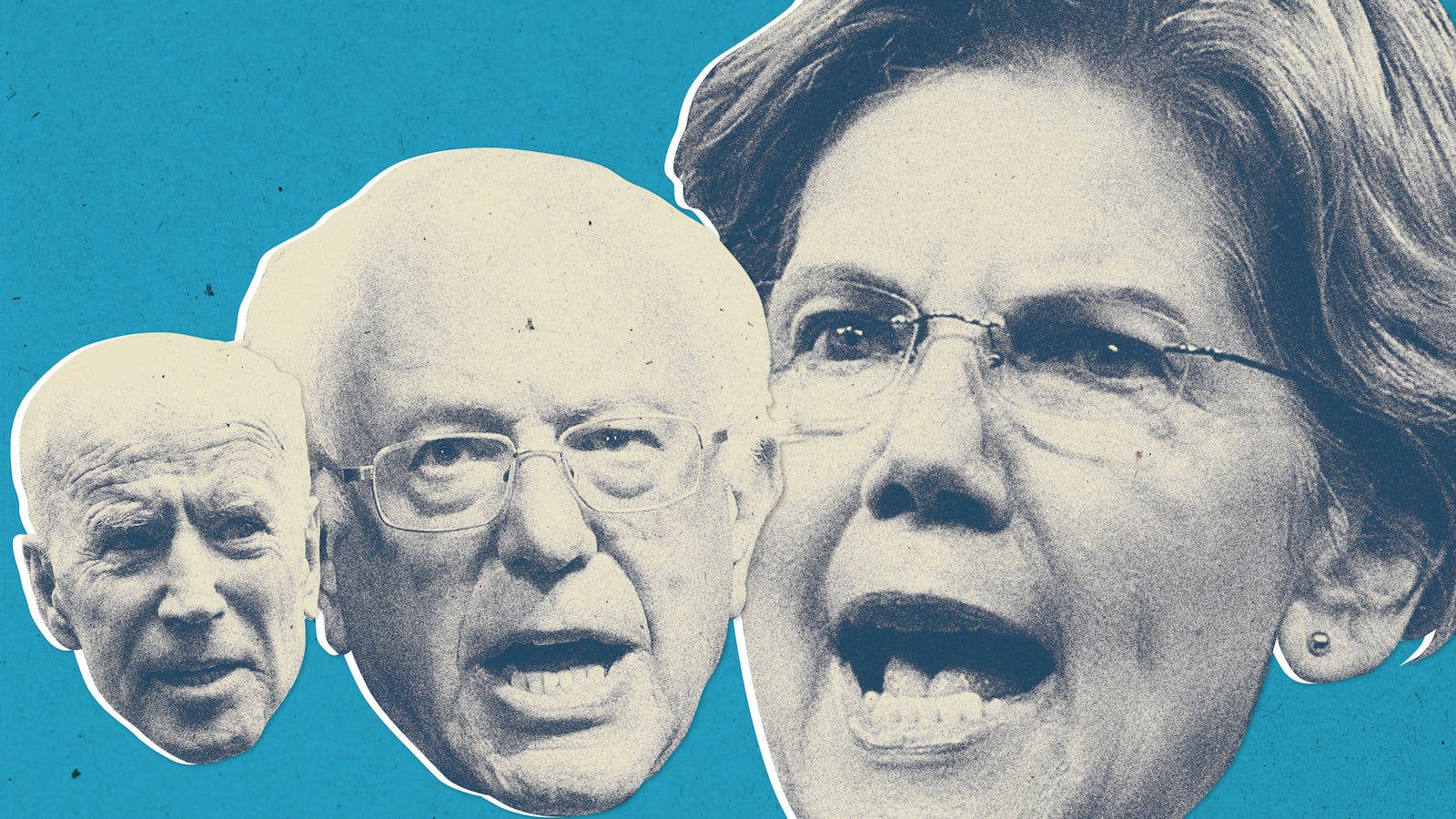

In tonight’s Democratic debate, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are in the same lane, buoyed by progressive activists wanting to make the “big structural change” Warren touts, and by the grassroots revolution Sanders promises.

But don’t expect them to collide.

Famously, the two have a so-called non-aggression pact, which is bad news for Joe Biden. He’s the one who will take Warren’s punches, not Sanders.

No one expects fireworks between Warren and Sanders even though Warren has gained ground in recent polls at Sanders’ expense, and the Houston debate stage presents an opportunity for her to differentiate herself as a self-proclaimed capitalist and not a Sanders-style democratic socialist. If she can do it purely on policy grounds, that wouldn’t violate the agreement she has with Sanders, her senior by several years, and in many ways her mentor.

“Both of them are going after a similar voting pool, and at some point some form of differentiation has to happen,” pollster Jefrey Pollock told The Daily Beast. “Maybe it gets fought out on the policy level. Voters want to see a contrast, but I don’t expect fire and brimstone in this debate.”

Pollock advised Kirsten Gillibrand until she left the race last month, so he understands firsthand the challenges a candidate faces in drawing the necessary contrast. On the debate stage, he cautions that Sanders is “much more unpredictable. He can pop off. [Warren] is far more likely to fight on a policy and academic level, and not rhetorically. That doesn’t mean she’s not willing to throw a punch.”

But that punch will likely land on Biden and not on Sanders. Background interviews with Democrats friendly to both the Warren and Sanders camps see the candidates going the distance in the primaries with one important caveat. Should Sanders fall behind Warren, there’s no assurance that he would leave the race. “He’s headstrong, he’s not going to say goodbye early,” says one Democrat. “You cannot rule out this could go to the convention.”

Democratic Party rules award delegates proportionately to candidates who get at least 15 percent of the vote—meaning there could be a pileup at the end of the primaries, with no one candidate able to claim the nomination outright. In that scenario, Warren would want Sanders’ delegates, and as long as she plays nice, it’s more likely Sanders would move over to Warren. “She’s playing very good politics now,” says this Democrat.

Sanders is a loner, without many friends in the clubby U.S. Senate, where he’s been a member since 2007. Warren, elected in 2012, worked hard to fit in and reached out to a lot of senators, including Sanders. “Senators from New England have to work on bills together,” says a Democrat who helped elect Warren. “They hit it off. They didn’t sign some democratic socialist pledge card.”

Sanders routinely called her “my favorite senator.” New York magazine reported that he was ready to defer to her in 2016—that if she ran for president, he would have stood aside. Warren stepped back, and the fraught relationship between Sanders and Hillary Clinton helped to create the phenomenon of the Bernie Bros or Berniecrats, who refused to support Clinton and voted third party or stayed home.

Another Democrat who is advising multiple campaigns on policy makes the case that Warren is better off with Sanders in the race: “He provides a kind of heat shield. Without Bernie, Warren becomes the crazy socialist.”

Furthermore, says this Democrat, “If I were advising Warren on politics, I would say, ‘Do not go after Bernie, you don’t have to do that. You don’t have to convert the Bernie Bros. The only thing that will get them is if he endorses you. You want to stay on Bernie’s good side. You don’t want to goad him into being the angry old man spoiler.’”

For the Sanders camp, the greatest imperative is to stay in the race, much like he did in 2016. “The longer he stays in, he can hold everybody’s feet to the fire,” says one of the party regulars in touch with both campaigns.

There’s no percentage at this point for Warren in trying to draw a distinction with Sanders unless it happens organically with a debate question that allows Warren to explain, for example, that she is working for change within the system while Sanders wants revolution—a distinction that Warren may better be able to pull off than Clinton, who radiated annoyance at Sanders spoiling her party.

“It’s Bernie as Larry David, and Senator Warren as someone trying to persuade you,” says Pollock.

Both camps seem content for now with voters making up their mind between two candidates, who are as different in their personas and approach as they are bound together by their policy views. Two for the price of one is a risky strategy, but it just might work.