Finally, the 2012 presidential race can begin. Herman Cain has gone to Iowa.

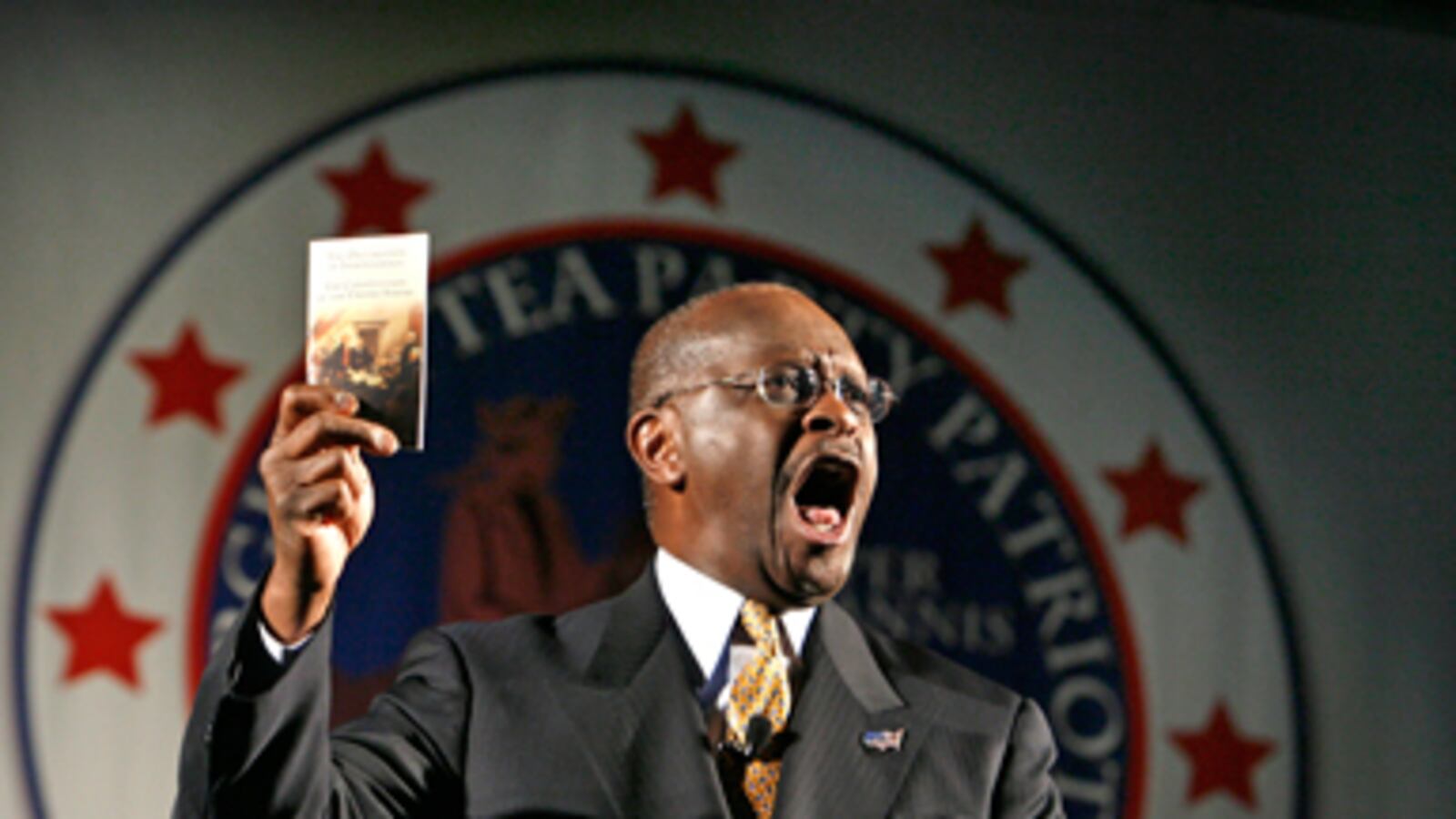

On Saturday, Cain was at Tish’s restaurant in Council Bluffs, a city in southwestern Iowa across the river from Omaha. Fifty or so GOP activists, Tea Party irregulars, and locals had gathered. Most of them had apparently heard of Herman Cain. When he entered, they gave him a standing ovation.

Cain, who is 65, is balding and bespectacled; he was wearing a white sweater vest and a button-down shirt. In a rich baritone, he began to talk about the GOP’s core issues. Taxes. Immigration. Abortion. He unfurled his life story- cum-résumé with the ease of a motivational speaker. Then Cain slid into his speech’s raison d'etre: the secret sign that made him, Herman Cain, think of running for president of the United States. “By that time,” says David Overholtzer, a GOP activist who was in attendance, “he had some of the moms tearing up.”

It’s now fair to ask: Who, exactly, is Herman Cain? Well, Cain is one of the most successful African-American food entrepreneurs in American history. His pal Jack Kemp once dubbed him “the Colin Powell of the restaurant industry.” Cain was Bill Clinton’s sparring partner during the 1994 health-care fight and, more recently, a fill-in for libertarian talk king Neal Boortz. In his only try for public office, he ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in Georgia. Now, Herman Cain says he thinks Americans might like him to be president.

“I’m more concerned about the legacy my generation will leave behind than I am about living a life in cruise control,” Cain tells me. On Wednesday—as Michael Steele, the nation’s most prominent African-American Republican, was facing defeat—Cain was forming an exploratory committee.

Cain is one of those people who will never be honored properly by the Iowa caucuses. So let us honor him while there’s still time. Cain grew up in the Bankhead neighborhood of Atlanta. His father was a chauffeur, a barber, and a janitor. His mother was a maid. Cain talks about this stuff all the time; he refuses to wear his biography lightly. In 1996, he was enshrined in the Horatio Alger Association.

Fast food was the first outlet for Cain’s raging ambition. In 1982, Pillsbury sent him to take over 450 Burger King restaurants, many of which were underperforming. Cain turned them around. In 1986, the company sicced him on Godfather’s Pizza, a chain of sad-sack pizzerias that were getting clobbered by Domino’s and Pizza Hut. Cain brought them to profitability and then, with his executive team, bought the chain himself.

“On the way to the airport,” Cain remembers, “I said to my friend, ‘Joel, have I lost my mind to think about running for president? … I’m tired! You should be taking me home!’”

It was in his capacity as a restaurateur that Cain achieved his first bit of political fame. In April 1994, Bill Clinton was stumping for his health-care bill. At a Kansas town hall, Cain rose from the crowd and said the bill would force Godfather’s to fire part of its workforce. Clinton parried and said Cain would only have to raise pizza prices by 2 percent. Cain, now openly contradicting the president, insisted Clinton was “incorrect.” The blast came as the coalition that might support Clinton’s plan was disintegrating, and the Hermanator—as he was by then calling himself—became a rock star. Cain “wasn’t the bullet” that killed reform, insists Chris Jennings, who was a senior health-care adviser to Clinton. But Newsweek dubbed Cain, not Harry and Louise, one of the “real saboteurs.”

Cain went national. He delivered up-by-your-bootstraps lectures for big paydays. He wrote four books and cut a gospel CD. He guested as a lay preacher on the Hour of Power and dabbled in talk radio as a fill-in for Boortz. “Research shows that people would rather listen to tapes than someone else when I’m away,” says Boortz, who has an audience of around 6 million. “But with Herman it didn’t turn out that way.” Now, Cain has his own nightly talk show on WSB in Atlanta, a mellow alternative to the surly precincts of conservative talk.

Listening to Cain’s show this week, I was struck by the fact that he is completely serious. He lacks the winking self-regard of previous fringe candidates like Alan Keyes and Dennis Kucinich. To callers who pledged their donations, Cain cautioned them that no one man could fix the country immediately. “But you haven’t been president,” one caller insisted. “That will all change.” Boortz says, “There’s not an ounce of doubt in my mind that he’s not only serious, but far more qualified for that job than the guy we have in there right now. This guy, he’s masterful, and somewhat of a philosopher. He has the tools. He really does.”

Did I mention that Cain survived Stage 4 colon and liver cancer in 2006?

Cain first got an inkling that he might have widespread support for his candidacy last April, at a conference in the Wisconsin Dells. After delivering a speech, he put on his trademark black hat, which is a hybrid of a cowboy hat and a Stetson. “I put the hat on, and I made the statement, ‘If we don’t start to see solutions coming out of Washington, D.C., in 2012, we just might have to elect a new sheriff to occupy the White House.’ The place went wild.” Cain will raise money. “My middle name is not ‘Meg Whitman,’” he says, adding he is not a “multi-kajillionaire.” Because he rarely deviates from GOP orthodoxy, Cain’s primary appeal will be oratorical. On Wednesday’s radio show, he was blasting away at “too much legislation, too much regulation, too much taxation. I call it the attack of the -ations.” But before he could really get going, WSB pre-empted him with a University of Georgia basketball game.

He registers at less than 1 percent in a recent Iowa poll. But in this pre-Romney moment, Cain is what we’ve got. I ask him to tell me the story that moved the women of southwest Iowa to tears—the secret sign that got him to keep running.

“Nineteen-ninety-nine is when my first granddaughter was born,” he says. “Her name is Celena.” Cain was on a long trip and thought he might miss the birth, but he arrived at the hospital in the nick of time. “As soon as I looked at [Celena’s] face,” he continues, “the first thought that went through my mind was, What do I do to make this a better world?”

“I didn’t know what that was going to mean, Bryan. I didn’t know exactly what I was supposed to do. I didn’t say then, ‘I ought to run for president.’”

Here comes the part of Cain’s story that really got those Iowans. Cain has a clarification about that: “They weren’t tearing up, Bryan. They were crying real tears, OK?” Even some of the men, apparently.

Anyway, back to the story: About a month ago, Cain was with his friend Joel, heading out on another grueling presidential-style exploratory jag. “He was taking me to the airport to go do another meet-and-greet somewhere in Iowa or New Hampshire. I don’t remember which one it was. And on the way to the airport, I said to my friend, ‘Joel, have I lost my mind to think about running for president? … I’m tired!

You should be taking me home!’”

Then, like a bolt from heaven, Cain got the sign. “Five seconds later,” he says, “Celena sent me a text. ‘Love you, Pa Pa. You’re awesome.’ That’s all it said. Five seconds later.”

“That’s when I told Joel, ‘Take me on to the airport.’”

Prediction: If the Hermanator isn’t destined to be the next GOP nominee, I’ll bet a million bucks he gets to speak at the convention.

Bryan Curtis is a national correspondent at The Daily Beast. He was a columnist at Play: The New York Times Sports Magazine, Slate, and Texas Monthly, and has written for GQ, Outside, and New York. Write him at bryan.curtis at thedailybeast.com.