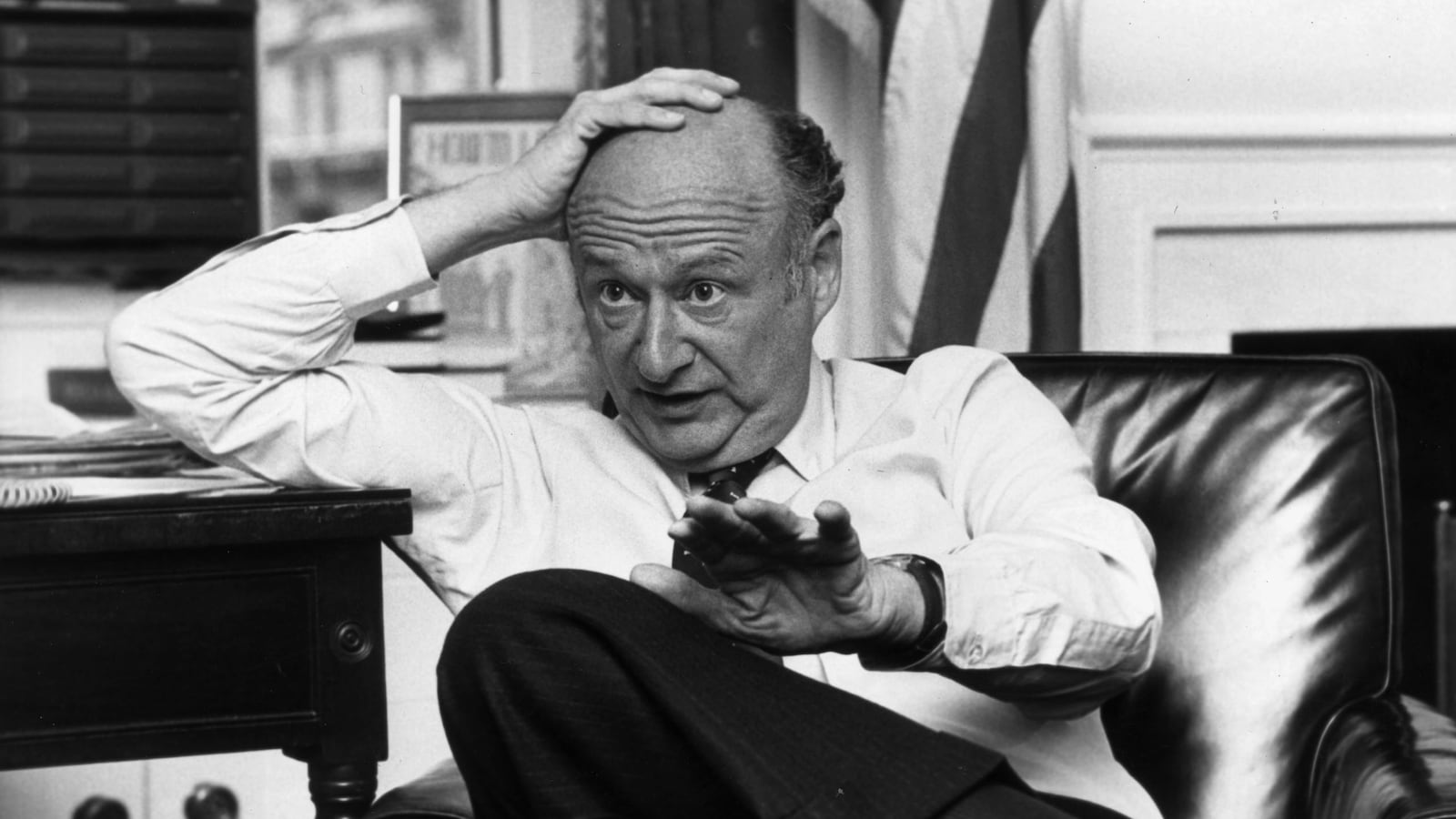

For a generation of Americans, and especially New Yorkers, Ed Koch was simply “Mayor.”

It was the title of his bestselling memoir, followed by a sequel, Politics, and even an off-Broadway tribute to Hizzonor. With typical talent for good timing, Koch departed this world at age 88, just days after the debut of a new documentary on his three terms at city hall. The news was announced by his longtime spokesman, George Arzt.

Here’s the elevator pitch: At a time when New York City seemed on its knees, inevitably on the decline, decadent, and in debt, Ed Koch’s exuberant common sense revived the City that was his one true love. He willed it back into health by helping New Yorkers believe again in themselves.

In truth, it was a model based on the Depression-era mayoralty of Fiorello La Guardia, but Koch updated the model with a 1970s style that was simultaneously no-nonsense and infused with showmanship. The Bronx-born World War II vet came of age in Greenwich Village reform politics, taking on the remnants of the Tammany Hall Democratic machine as a self-described “liberal with sanity.”

His rise to the “second-toughest job in America” was not fueled exclusively by the idealism of Washington Square. Instead, Koch positioned himself as the unexpected champion of the middle class. After climbing from City Council to Congress, Koch’s first campaign for mayor was framed as a repudiation of liberal excess and the ensuing civic decay. “This city is like it has never been before, with people at one another’s throats, suspicious of their neighbors, angry with their government, frustrated that no one in authority seems to care or even wants to listen ... As walking the streets of this city became a lottery of life and death, as business and industry fled to the suburbs or beyond, as corruption has been uncovered at deeper and deeper levels of city government, more and more people have begun to think that perhaps New York really is ungovernable after all.”

He won his first mayoral campaign in 1977, defeating pint-size City Comptroller Abe Beame, who presided over the city’s fiscal failure (commemorated by the Daily News headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead”) after John Lindsay’s libidinous late-’60s administration. Four years later, Koch was back at it, looking for vindication. It was the season that the Yankees’ playoff appearance was crystallized in the minds of Americans by Howard Cosell gazing at arson flames from the press box of Yankee Stadium and announcing, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.”

It was not a time of urban optimism. People were fleeing the city for the suburbs, and it was generally accepted that Gotham’s best days were behind it. Koch believed otherwise, making a frank pitch to his would-be constituents: “After eight years of charisma and four years of the clubhouse, why not try competence?”

It worked.

His first four years were glorious. After taking the oath of office in what The New York Times described as a “rust-colored tie,” Koch invigorated the city. He took on the unions that were again attempting to extort New Yorkers with well-timed strikes. In one memorable early standoff, Koch stood on the Brooklyn Bridge, waving bicycling commuters into lower Manhattan, encouraging their defiance against the transit-worker stranglehold on city finances. He proved such an effective steward of the city budget that in his 1981 reelection he was nominated by both the Republican and Democratic parties—an impressive anomaly that spoke to his broad support.

But in his second term, Koch began to enjoy being the mayor more than actually doing the job, according to longtime New York City observer Fred Siegel, a scholar in resident at St. Francis College and senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. “When he got bit by the gubernatorial bug, things started to go downhill,” says Siegel. Albany eluded him, but for a while Koch was even mentioned as the possible “first Jewish president” and celebrated on magazine covers, back when that distinction defined the news cycle nationally. He won a third term with an astounding 78 percent of the vote against two competitors in 1985.

Buoyed by a healthy self-image columnist Jack Newfield commemorated by saying that “Ed Koch is like a rooster who takes credit for the sunrise,” Koch was a pugilist perfectly suited to the city’s tabloid press, quick with contentious soundbites guaranteed to land him on the front page. His signature phrase—“How’m I doing?”—became iconic. Decades later, he is at least as well known for his classic quotes as his accomplishments in office. Among his best:

· “If you agree with me on 9 out of 12 issues, vote for me. If you agree with me on 12 out of 12 issues, see a psychiatrist.”

· “I am the sort of person who will never get ulcers. Why? Because I say exactly what I think. But I am the sort of person who might give other people ulcers.”

· “The fireworks begin today. Each diploma is a lighted match. Each one of you is a fuse.”

· “In action be primitive; in foresight, a strategist.”

Koch remained politically relevant in part by remaining unpredictable—a Democrat who endorsed Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush for reelection, providing potent cover for liberals who wanted to stray outside their party lines.

His third term was beset by scandals, none of which ever implicated Koch personally, but the gravitational pull of party bosses and genial clubhouse crooks started to outweigh the lean and hungry reformer who first entered office. Long dogged by tensions with New York’s African-Americans and much criticized, unfairly in his view, by activists during the height of the HIV crisis, he narrowly lost a contentious primary for an unprecedented fourth term in 1989 to Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins, who ran on a promise of healing race relations and a vision of New York as a “gorgeous mosaic.” But even in defeat, Koch provided a memorable soundbite when asked if he would run again: “The people have spoken ... And they must be punished.”

Dinkins then bested Rudy Giuliani in a tightly contested general election, only to preside over unprecedented murder rates and a crumbling economy before losing an equally tight rematch four years later.

In Koch’s semi-retirement, from the comfort of a Greenwich Village apartment, he remained a political player and sometime kingmaker, always quick with a memorable quote for reporters on deadline. In Ric Burns’s epic New York City documentary, Koch played the role of joyful-eyed elder statesman, which somehow did not conflict with his syndicated turn judging The People’s Court, a cameo in The Muppets Take Manhattan, or his occasional mystery novels and reviews and regular film reviews. He was a man in full who was alternately flattered and hostile to enduring questions about his sexuality, even into old age: “I find it fascinating that people are interested in my sex life at age 73. It's rather complimentary! But as I say in my book, my answer to questions on this subject is simply ‘Fuck off.’ There have to be some private matters left.”

For all his flinty wit and occasional impulse to antagonize, Ed Koch was, in the end, almost impossible to dislike. In this, he reflected his city.

Ed Koch was a New York icon and an American original. He will be missed but not forgotten.