For thousands of unwitting residents of Colorado and Washington, the reach of the nation’s opioid addiction crisis just got closer to home.

As reported by The Seattle Times, patients who underwent surgery at two area hospitals over the span of several months from 2011 to 2012 are being contacted and told to be tested for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Concern about possible exposure to these blood-transmitted illnesses stems from the indictment this year of a man briefly employed as a surgical technician at both institutions.

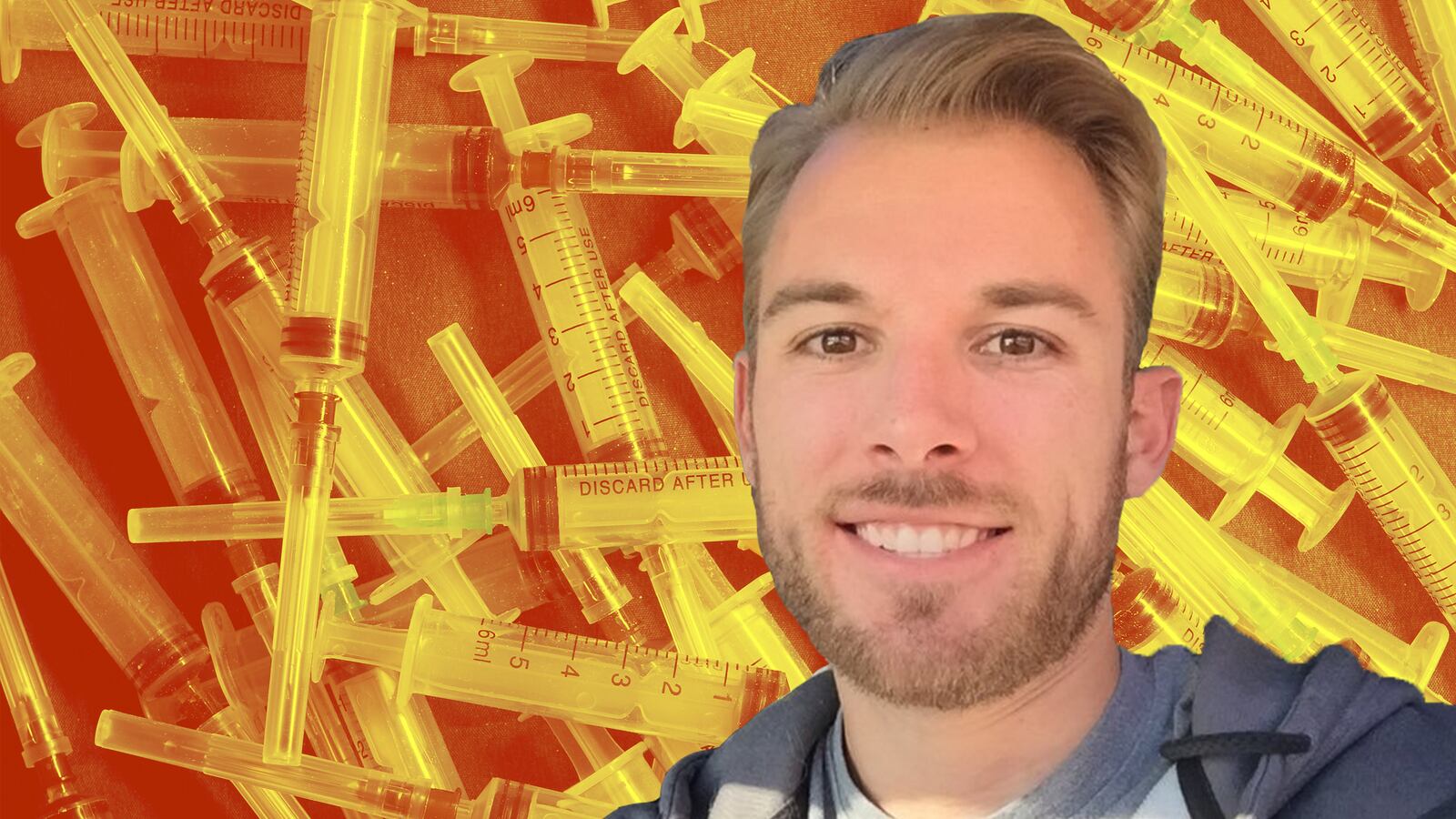

Rocky Allen, 28, was indicted this February in Denver on charges of tampering with a consumer product and obtaining a controlled substance by deceit. According to the indictment, in January Allen swapped a syringe containing the narcotic painkiller Fentanyl for a similar syringe filled with an unspecified substance. At the time, he was working at that city’s Swedish Medical Center, and as in Seattle, thousands of Colorado residents who had surgery there are now advised to get tested for the same illnesses.

Because the potentially tainted Fentanyl is an injected medication, if other substitutions by Allen went undetected, screening for blood-borne infections is prudent.

The recommendation to be tested springs from an “overabundance of caution,” according to Karen Peck, a spokesperson for Northwest Hospital and Medical Center, one of the two Washington hospitals where Allen had been employed. (The other, nearby Lakewood Surgical Center, has issued similar advice to a little over 100 patients who received care there when Allen was an employee.) A statement from Northwest stresses that there is no evidence that any patients there were actually exposed to tainted medication, and that actual risk is extremely low.

“We know patients are very concerned,” Peck told The Daily Beast. However, while an investigation is ongoing, at this time there is no evidence that Allen made a similar swap while employed there. Peck hastened to reassure that patients currently receiving care at Northwest are not being exposed to risk.

Fentanyl is a particularly potent opioid pain medication, and comes in numerous dosage forms. It is often used as an adulterant or substitute for heroin, and using both in combination poses a substantial risk for overdose.

This week, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued new guidelines for prescribing narcotic pain medications. In its report, the CDC notes that since the turn of the new century over 165,000 people have died of such overdoses. Over the past decade, this trend has been on the incline, in contrast to falling rates of death from other causes like heart disease and cancer. This increase in mortality parallels the increase in sales of opioid medications (which also includes drugs like Oxycontin and Vicodin, among numerous others). The authors note that in 2012 alone, enough of these prescriptions were written to supply every adult in America with their own bottle.

In an attempt to stem this tide, the CDC advises that for management of pain lasting more than three months, non-pharmacological and non-opioid medications are preferred. For those for whom narcotic prescriptions are appropriate, providers should proceed with caution, starting with low-dose, short-acting options.

Of course, there are times when such prescriptions truly are appropriate. The period immediately after major surgery would certainly be one of them. Medications like Fentanyl are often necessary for patients who are being treated for truly painful conditions.

But as the situation plays out in Washington and Colorado, it serves as a stark reminder that the fallout from the opioid addiction crisis can land in very unexpected places. Even patients whose own pain management was entirely appropriate have now been affected by it, albeit distantly. Efforts to combat the growing health problem are needed not only for those now struggling with addiction to pain medication, but for those who might be touched by it in ways they could never have predicted.