The House of Representatives voted by an overwhelming margin on Thursday to condemn “the horrors of socialism.”

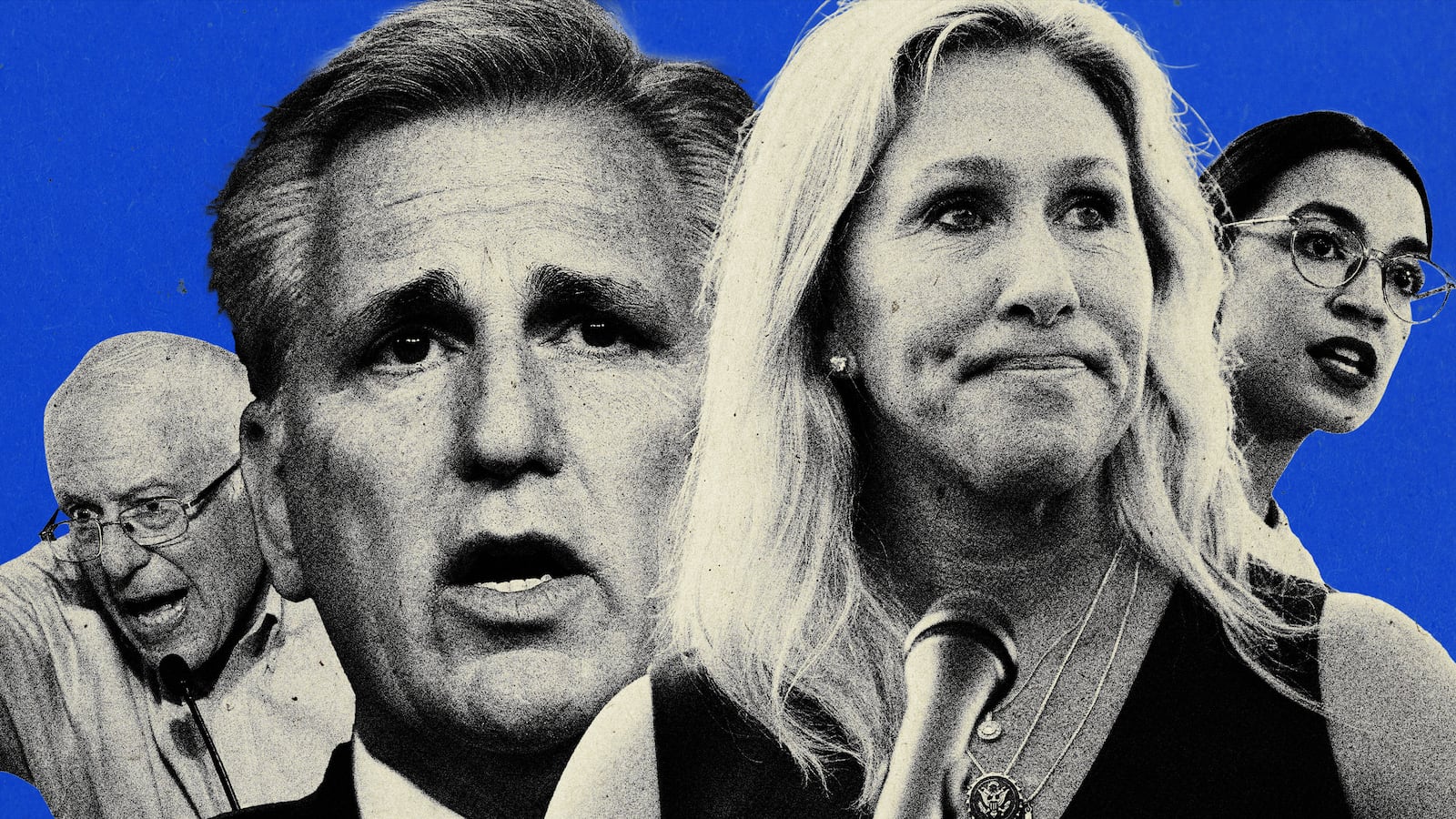

It’s obvious that the real targets are politicians like Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. But instead of explaining what’s wrong with popular democratic socialist policy proposals like Medicare for All or eliminating tuition at public universities, most of the resolution is wasted on denouncing the real or alleged “horrors” committed by authoritarian dictatorships with no resemblance to anything advocated by democratic socialists.

The text is a mess. It’s full of bad history, sloppy definitions, and extreme libertarian rhetoric. It reads to me like the work of nervous ideologues who worry that the s-word is losing its power to terrify ordinary Americans.

Rewriting History

The resolution starts by claiming that “socialist ideology necessitates a concentration of power that has time and time again collapsed into Communist regimes, totalitarian rule, and brutal dictatorships.”

If your understanding of “socialism” comes from vague memories of the Cold War, it might be easy to nod along with all of that. But what does it mean?

“Socialism” (or even “democratic socialism”) can be interpreted in two ways. These phrases can refer to either a new economic system that would replace capitalism the way capitalism replaced feudalism at any earlier time in history—or “socialist policies” like Medicare for All that could be carried out right now without waiting for a completely new system.

Many socialists, myself included, support such “socialist policies” both as a way of improving the lives of working-class people in the here and now, and as baby steps in the direction of deeper changes to the economy in the long run.

None of that “necessitates a concentration of power.” In fact, exactly the opposite is true.

To see why, think about the long-term vision of a fully democratic socialist economy replacing the corporate capitalism we have now. That would mean that what socialists call “the means of production”—factories, farms, grocery stores, warehouses, mines, construction sites, you name it—would be collectively owned and democratically run by the workers themselves or the larger communities they’re part of instead of either being owned by individual rich people or having bits and pieces of them bought and sold by stockholders.

That change would make power far less concentrated. Imagine, for example, that Amazon was structured as a worker-owned cooperative. Would warehouse workers vote to let the founder of the company keep so much of the money everyone made with their collective efforts that he could afford his own spaceship while many of the rest of them had to work second jobs? Would they vote to give themselves such demanding quotas, enforced by constant electronic surveillance, that many of them would end up skipping bathroom breaks and peeing in bottles to keep up the pace? Of course not. Those are the kinds of abuses that can only happen when power is concentrated at the top of the economic ladder, the way it is under capitalism.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT)

Reuters/Carlos BarriaAnd even short of that long-term vision of a socialist utopia, power is more diffused when strong labor unions and a strong regulatory state stop wealthy capitalists from just doing whatever they want to everyone else. And the more universal government programs there are—like Medicare for All—the less working-class people need to rely on the goodwill of their bosses to meet their basic needs. That helps chip away at the concentrated power of wealthy elites.

There are many historical examples of governments that were influenced by “socialist ideology” coming to power through democratic elections—with wildly varying results. Some have carried out major reforms that dramatically improved the lives of working-class citizens, even if they never completely got past capitalism.

Sweden and Norway, for example, remain to this day among the most livable societies in human history, in large part due to the accomplishments of the socialist parties that have repeatedly held power in those countries. In other cases, such parties achieved power but caved to pressure from business interests and acted like tepid liberals or even instituted economic austerity. And of course there are several cases, such as that of Salvador Allende’s government in Chile, of democratically elected socialist governments being overthrown by CIA-backed coups.

But one thing that has literally never happened—not once in the history of the world—is that a democratic socialist party has come to power in some country through a multi-party election and then just sort of “collapsed into” Soviet-style Communism.

It’s true that when Communist dictatorships did arise in various countries as a result of revolutions, civil wars, coups, or invasions, they often committed all-too-real abuses and atrocities. But, crucially, so did dictatorships that oversaw capitalist economies. The absence of political freedom opens the door to the possibility of extreme state brutality whether or not it’s paired with the absence of free markets.

Indonesia’s Suharto, for example, was a dictator who was backed to the hilt by the United States for standard Cold War anti-Communist reasons. And he was every bit as murderous as even the worst of his counterparts on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Such inconvenient facts are airbrushed out of the House resolution’s narrative.

Former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez

Reuters/Jorge SilvaAnd at least one of the horrors that properly belongs to the Western side of the Cold War is simply transferred to the other column. The House resolution luridly describes Cambodia’s “Killing Fields” without mentioning that, when Communist Vietnam invaded Cambodia to stop those atrocities, the United States openly backed Pol Pot to make trouble for Vietnam and its Soviet patron. That’s not a secret. The United States, for example, voted in the United Nations to give Cambodia’s seat to Pol Pot instead of the Vietnamese-allied government he was resisting.

Of course, including facts like that would ruin a perfectly good morality tale.

Being Serious About Venezuela

Probably the closest thing to a real example of a democratic socialist government “collapsing into” something closer to Soviet Communism is Venezuela. Hugo Chavez was elected on a fairly moderate platform in 1998, but he moved to the left and adopted socialist rhetoric in the 2000s.

While Chavez himself won multiple internationally monitored elections after that point and respected the results of a referendum he lost in 2007, his successor Nicholas Maduro has acted in far more authoritarian ways.

Conservatives often put this fact together with the economic crisis in the Maduro era—a crisis that’s been variously blamed on currency mismanagement, corruption, American sanctions, or some combination of the these factors—and portray Venezuela as a “Communist dictatorship” and object lesson about where the path of socialist economics leads. Predictably, there’s quite a bit of this kind of rhetoric about Venezuela in the House resolution.

But there’s a big problem for this narrative. There’s simply no metric of state involvement in the economy that would make Venezuela more socialist or communist than several democratic nations in Europe. Even at the height of Hugo Chavez’s welfare state in 2012, the Venezuelan public sector employed a smaller percentage of the population than the public sectors in Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and even France.

Norway is a particularly good comparison point since oil (and state-owned oil companies) play similar roles in their economies. But the Norwegian public sector is a bigger employer and the Norwegian government holds far more of the country’s wealth. If Venezuela is a “socialist” basket case, Norway is…what…a “super-socialist” success story?

“All Forms of Socialism”

The full ideological agenda of the resolution comes into focus in the final sentences, when the focus finally shifts away from a recitation of the sins of foreign governments to live political issues in twenty-first century America. The resolution condemns any attempt to interfere with the existing distribution of economic resources, backing the condemnation with references to the Founding Fathers.

Apparently Thomas Jefferson, for example, thought that taking from those “whose industry and that of his fathers” has led to the acquisition of great wealth to help “others, who, or whose fathers have not exercised equal industry and skill” violated “the first principle of association, the guarantee to every one of a free exercise of his industry, and the fruits acquired by it.”

The concluding line of the House resolution declares that “Congress denounces socialism in all its forms, and opposes the implementation of socialist policies in the United States of America.”

Presumably the point of the phrase “all its forms” is to make clear that the condemnation applies not just to the state socialism of the Soviet Union or Mao’s China but the “democratic socialism” of Bernie Sanders. But the Jefferson quote, taken seriously, would cast a much wider net than that.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA)

Reuters/Elizabeth FrantzPublic schools, for example, tax the fruits acquired by the industry of those who may be able to afford to send their kids to private schools. And Social Security and Medicare help those whose industry during their working years was insufficient to provide them with adequate retirement savings.

Congressional Republicans would doubtless insist that they don’t mean to object to public schools or Social Security. That would be extremist!

But the problem here goes deeper than sloppy writing in the resolution. There’s simply no coherent way to condemn “socialist policies” in general as tyrannical without casting a very wide net. If Medicare for All violates “the first principle of association,” why doesn’t Medicare for seniors? If taxpayer-funded public education, provided to every pupil free at the point of service up through the senior year of high school doesn’t violate that first principle, how is it that it starts to violate it when it’s extended to the first year of college?

Just Political Theater?

Many Democrats have condemned the resolution as a pointless distraction. It’s easy to see why. It’s not as if the U.S. government was on the brink of nationalizing the means of production before Congress swung into action. And even if it had been, a non-binding resolution would have done nothing to stop that from happening.

The real goal was to divide and embarrass Democrats and isolate the handful of socialists in Congress by forcing the rest of the caucus to either condemn them or publicly take their side. And, to an extent, it worked—109 Democrats voted for the resolution. Even Rep. Ro Khanna of California, who chaired Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign in 2020, bent his knee to the fearmongers and voted “yay.”

But in another way the gambit backfired.

If the House had bothered to vote to “condemn socialism” ten years ago, there might not have been a single “nay” vote. If it had done it 20 years ago, when Bernie Sanders was still in the House, there would have been one.

In 2023, there were 86 “nays,” and 14 Democrats who awkwardly voted “present.” Too many of these members’ constituents associate the s-word with immensely desirable proposals for social reform—and with a broader sense of dissatisfaction with the economic status quo—for performatively condemning socialism to be the completely cost-free vote it would have been even in the very recent past.

I don’t want to exaggerate the progress. Given the current balance of power in national politics, even Medicare for All is a long way away. American capitalism isn’t going anywhere any time soon. But, little by little, that system’s most fanatical defenders are losing ground in the ideological war.