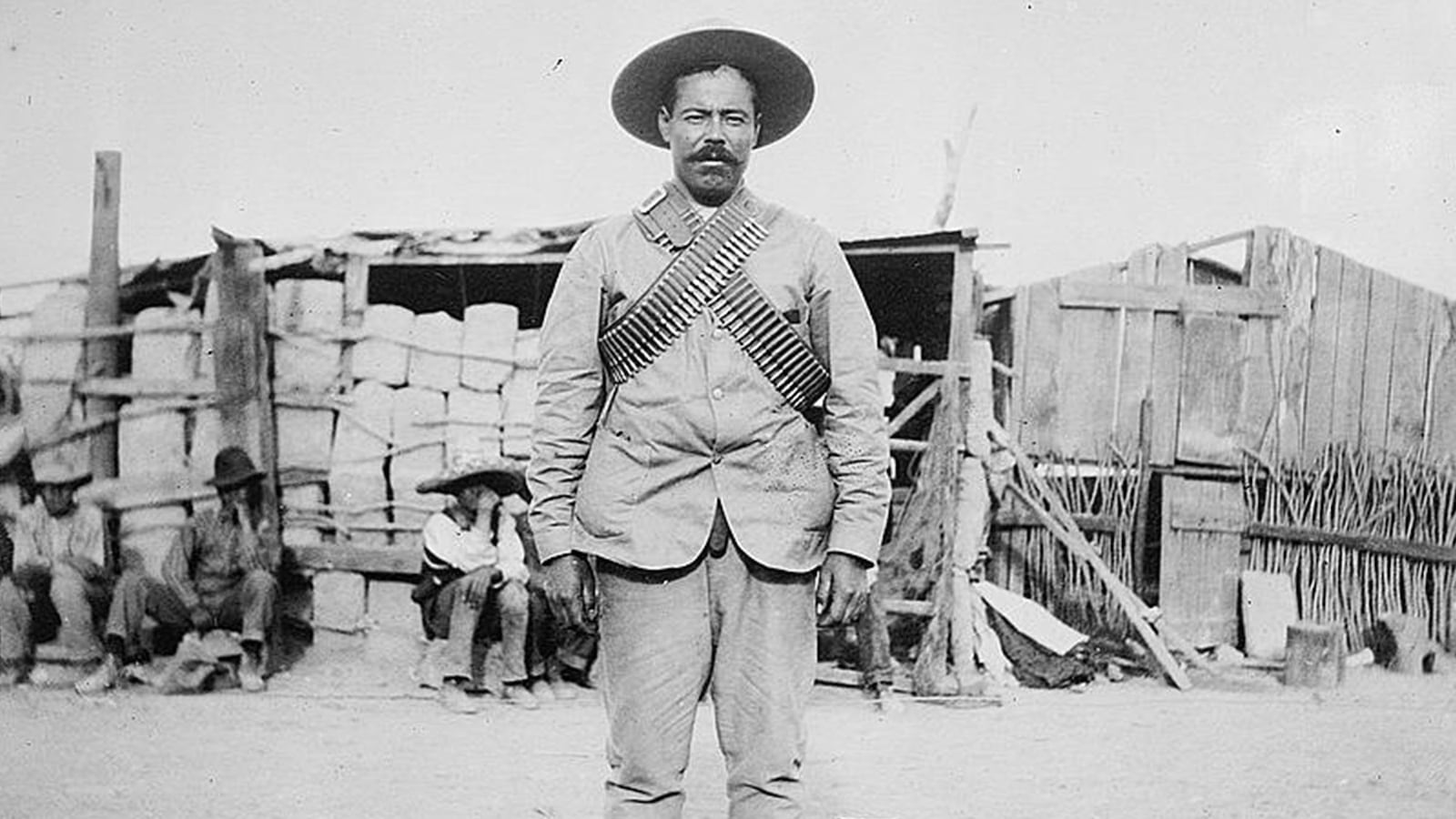

On January 7, 1914, a front-page story in The New York Times announced two seemingly incongruous pieces of information: Pancho Villa, a rebel leader in the Mexican Revolution that had gripped the attention of the American public, had just arrived in Ojinaga.

Riding in on his pinto pony wearing a “big sombrero flapping in the breeze” and proceeded by his bugler, Villa was preparing to personally lead his troops in an attack on the country’s federal forces who were entrenched in the northern Mexico town.

General Villa, the headline announced, had also just been signed up by the “movies.”

Thirteen years before the first “talkie” would premiere and 96 years before Instagram would try to make influencers out of us all, a savvy Mexican general with a “reputation as a bandit” realized the power the burgeoning Hollywood industry had to craft an image and sway public opinion. With an eye toward shoring up support for his cause, Villa signed an exclusive deal with the Mutual Film Corporation to allow the movie company’s cameramen to join his troops and film their upcoming operations.

The result was the feature film The Life of General Villa which premiered in New York City in May 1914. It was perhaps the earliest foreshadowing of the reality TV era of today, a film about the life of Pancho Villa starring Villa himself, that was just as much fiction as it was documentary.

The record on this movie remains sparse, but by most accounts its debut was received with great excitement and acclaim. But within just a few years, the film had disappeared. While bits and pieces of the original war footage have been found, today, The Life of General Villa exists mostly in legend.

“They had someone who was already, for all intents and purposes, a celebrity”

World War I is often given credit as being the first televised conflict, but that dubious honor—or at least the initial seeds of it—belongs in part to the Mexican Revolution.

It was “the first cinematic war or the first war waged through the new mass media of cinema,” Colin Gunckel, film scholar at the University of Michigan, told The Daily Beast.

In 1910, a political revolt began against dictator Porfirio Diaz, who had ruled as president of Mexico for 34 years. The rebellion was not a tidy two-sided affair. Rather, several different factions throughout the country fought their own battles against the federal forces.

While the American public was captivated by the conflict on their southern border, the U.S. political and business classes fretted about which of these revolutionary leaders to throw their support behind. Villa may have had a reputation as a brash bandit, but he managed to build a wide-ranging coalition in the U.S, at least for a little while.

“One of Villa’s most remarkable achievements was that he won not only the support of conservative businessmen, generals, and the Wilson administration, but also the admiration, for a time, of substantial segments of the American left, which opposed the businessmen who regarded Villa so highly,” Friedrich Katz writes in his biography of the general, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa.

To help solidify this backing and to make some money for his campaign, Villa turned to Hollywood.

It was an auspicious time in the development of “the pictures” for a larger-than-life revolutionary to enter the scene. The newsreel—a precursor to televised news coverage—had just been invented and every film company was eager to get their hands on novel footage. At the time, Hollywood was also starting to explore the idea of feature films as well as that of individual stardom.

“In the case of Pancho Villa, they had somebody who already had international renown,” Gunckel says. “They didn’t have to manufacture or develop an actor into a star; they had someone who was already, for all intents and purposes, a celebrity.”

Villa, for his part, knew a good opportunity when he saw one.

Who approached whom has been lost to history. But what is known is that, at the beginning of 1914 just after Villa had taken Juarez, a representative from the Mutual Film Corporation traveled down to Mexico and signed an agreement with the general.

The one-picture deal stated that, in exchange for $25,000 and 20 percent of the film profits, Villa would allow the company exclusive access to film him and his troops as they engaged in battles and other wartime operations.

While the myth surrounding the filming of The Life of General Villa has grown to suggest that the cameramen were also given permission to in part “direct” the warfare, among other things to ensure that attacks occurred during optimal lighting, most evidence suggests this wasn’t entirely the case.

But the effect of the cameras on real-life events was something that Harry E. Aitken, president of the Mutual Film Corporation worried about.

The day the news of the contract broke, Aitken told The New York Times, “It is true. I am a partner of Gen. Villa. It’s a new proposition, and it has been worrying me a lot all day. How would you feel to be a partner of a man engaged in killing people, and do you suspect that the fact that moving picture machines are in range to immortalize an act of daring or of cruel brutality will have any effect on the warfare itself? I have been thinking of a lot things since I made this contract.”

But pesky concerns about ethics couldn’t stop the show. By the time news of the contract broke, 10 cameramen were already on the front lines.

D.W. Griffith, the infamous director responsible for producing The Birth of a Nation the following year, was originally supposed to spearhead the Villa project. But his busy schedule got in the way, so Christy Cabanne took over, with Raoul Walsh serving as the assistant director-cum-cameraman in Mexico-cum-actor who portrayed the young Villa.

Walsh would become a famous director in his own right and, by the end of his life, he was as renowned for his film work as he was for fabricating parts of the plot of his own history. As his biographer Marilyn Ann Moss wrote, “If he was not creating a story for the big screen, he was creating one for his own life.”

So, it’s important to take Walsh’s account with a grain of salt. But his portrayal of the interaction between the Mutual Film Company cameras and Villa’s activities still gives us a vivid picture of the experience on the frontlines of the Mexican Revolution.

In one statement Walsh later gave, he complained about the logistics of shooting scenes of Villa on his horse (“I don’t know how many times we said, ‘Despacio, despacio—slow—Señor, please!’”), before going into more gruesome—and ethically harrowing—details.

“I used to get him to put off his executions,” Walsh said. “He used to have them at four or five in the morning, when there was no light. I got him to put them off until seven or eight. I’d line the cameramen up, and they’d put these fellows against the wall and then they’d shoot them. Fellows on this side with rocks in their hands would run in, open the guys’ mouths, and knock the gold teeth out. The fellows on the other side would run in and take the shoes and boots off them.”

While the feature film may not exist, some of this newsreel footage was discovered in the early aughts by Gregorio Rochas, a documentary filmmaker from Mexico. Clips from the black-and-white footage that appear in Rochas’s documentary, The Lost Reels of Pancho Villa, are as macabre as Walsh suggests.

While the final 1914 movie did contain actual scenes from Villa’s war, including the man himself, not all of the on-the-ground footage was up to snuff.

This semi-fictional feature film needed drama. The Mutual Film Company created this by way of fictionalizing much of Villa’s back story, but they also decided to reshoot many of the battle scenes on location in California where they could control things like lighting and the cowboy stuntmen riding into battle. They used the same field that would be used just a short while later to film the battle scenes of The Birth of a Nation.

The Life of General Villa premiered to much excitement. The film fed the U.S. audience’s obsession with the Mexican Revolution, and was even more acclaimed for starring General Villa himself.

But its popularity appears to be relatively short-lived, possibly as a result of the actions of the film’s star.

At the beginning of 1916, the Wilson administration began to support one of Villa’s rivals. In response, Villa and his troops attacked Columbus, NM, on March 9, 1916 and killed 19 American residents. With that, U.S. public favor abruptly turned against the general.

It may have been this loss of popularity, or maybe it was simply a result of the film industry’s practice common at the time to reuse past movie reels to make new movies. Either way, it seems that not too long after The Life of General Villa premiered in 1914, it had disappeared into the annals of film legend.

The loss goes beyond that of an important film of the silent era; it also would have been an interesting historical document.

Gunckel notes that the portrayal of Mexico in the U.S. changes after 1916 when “the Mexican Revolution and people involved like Pancho Villa kind of get pulled into these longstanding stereotypes about Mexico and Mexicans…The cinematic representation and general attitudes about the revolution get folded into these negative stereotypes.”

But while the true story of Villa remains as elusive as the semi-fictional film made about him, one artifact from his life as a movie star remains.

There is a famous photo of Villa sitting atop his horse, sombrero jauntily perched on his head, with his distinguished mustache expertly coiffed that has come to be considered the quintessential photo of the famed general. This image, Gunckel says, was taken by the Mutual Film Corporation camera crew in hopes of using it in their next feature film.