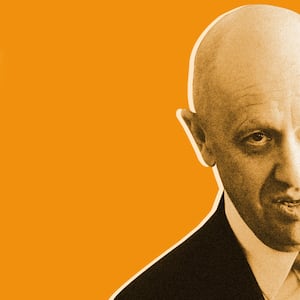

The world has learned a lot about Yevgeny Prigozhin since American authorities first filed criminal charges against him two years ago for alleged financial ties to the internet troll farm accused of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Known as “Putin’s Chef” due to his vast Kremlin catering contracts, Prigozhin has also been sanctioned by the U.S. for his alleged ties to Russian mercenaries affiliated with the Wagner Group. Now, leaked data from several sanctioned Russian firms linked to Prigozhin’s business networks reveals that key Prigozhin associates have helped one of his political consultants infiltrate a high-level United Nations panel.

Prigozhin’s alleged mercenary army provides intelligence and paramilitary fighters all over the world. The U.S. Treasury links it directly into President Vladimir Putin’s chain of command describing the shadow military as “a designated Russian Ministry of Defense proxy force.”

Evidence of Russia’s apparent campaign to install a Prigozhin connected operative on a U.N. panel charged with monitoring the arms embargo on Sudan comes less than a month after European Union authorities levied sanctions against Prigozhin for alleged breaches of a U.N. arms embargo on Libya. Analysis of leaked travel and billing records for Prigozhin-linked companies and email correspondence between a senior Russian diplomat and Nikolai Dobronravin, a St. Petersburg State University professor and expert in African energy affairs, indicates that Dobronravin worked as a consultant for two Prigozhin-linked firms that paid for his travel to the Central African Republic in September 2017.

Dobronravin was first appointed to the panel in March 2018, giving him a catbird seat over the leading U.N. body responsible for monitoring the security sector as well as human rights and arms embargo violations in Sudan. The Kremlin has long pushed for easing sanctions against Sudan, and an end to the U.N. peacekeeping mission in Sudan’s troubled Darfur region. Eager to expand Russia’s military and economic ties to Red Sea coast countries, Putin began aggressively cultivating ties with Sudan’s long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir, inviting him to Moscow and signing off on a military-technical agreement and an array of mining and aid deals in 2017, despite a standing international warrant for Bashir in connection with alleged war crimes still pending at the International Criminal Court.

Despite Bashir’s downfall in 2019, the Kremlin’s long campaign to expand its influence appears to be bearing more fruit by the day with the announcement in early November that Sudan has agreed to allow Russia to open a naval logistic center in Port Sudan. The Russian naval hub will likely be a critical node for Sudanese gold exports, which have proven a boon not only for several mining companies linked to Prigozhin but this time for Russian state coffers. Russia has invested heavily in building up its gold reserves to help stabilize the rouble and futureproof its economy against harsher Western sanctions.

In early 2018, around the same time Dobronravin’s candidacy on the U.N. Sudan panel was under review, Russian companies with ties to Prigozhin also agreed to work closely with Bashir’s one-time protégé and leading strongman Mohamed “Hemedti” Hamdan Dagalo to cut gold mining exploitation deals. Hemedti, who heads the country’s Rapid Support Forces and now serves as deputy chair on the transitional government’s ruling civilian-military council in Khartoum, reportedly has close family ties to Algunade, a Sudanese gold mining company. The RSF, for its part, oversees security for gold industry sites in the Darfur region and province of South Kordofan. Russian employees of St. Petersburg-based M-Invest, and Lobaye Invest, two companies linked to Prigozhin, have been implicated in the 2018 murder of three Russian investigative journalists in the Central African Republic, or CAR, as well as mercenary operations in Libya and a sweeping online disinformation campaign led by the Internet Research Agency aimed at propping up dictatorships in multiple African countries, including Madagascar, Mozambique, and Sudan.

The St. Petersburg-based firms that at least partially financed Dobronravin’s research trip to CAR—M-Invest and EvroPolis—are part of the same sprawling network of shell companies, several of which have been sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department for sending Wagner Group mercenaries to Sudan to “suppress and discredit protestors seeking democratic reforms” and waging a massive disinformation campaign against Sudanese democratic activists in 2019. Treasury officials have said that Prigozhin holds a controlling interest or beneficial ownership stake in M-Invest, EvroPolis, Lobaye Invest, the Internet Research Agency, and several other companies that operate in Africa.

In February 2018, U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller and his team brought charges against Prigozhin and several other employees and associates linked to Prigozhin’s businesses, including Concord Consulting and Management, for alleged election interference in the U.S. In March of this year, U.S. Department of Justice officials dropped the election fraud charges against Concord and a related company, Concord Catering, because of reported concerns that pressing the case further would reveal sensitive information about sources and methods U.S. authorities used to investigate Prigozhin and the Internet Research Agency.

In March 2019, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres renewed Dobronravin’s term on the U.N. panel of experts on Sudan. During 2017 and 2018, when records indicate Dobronravin was in close contact with a number of Prigozhin’s business associates, Dobronravin also corresponded frequently with senior Russian officials in the ministry of foreign affairs about his pending application to represent the Russian federation first on the U.N. panel of experts for Central African Republic sanctions then on the Sudan panel, leaked documents show.

Prigozhin’s associates Mikhail Potepkin, Dmitry Sytii, Alexander Kuzin, and Yevgeny Khodotov first came to the world’s attention two years ago, shortly after international press reports surfaced suggesting that three Russian journalists had been killed while investigating the Wagner Group in CAR in July 2018. In August 2018, the Committee to Protect Journalists called for the investigation into the killing of Russia’s top war correspondent Orkhan Dzhemal, and his colleagues Alexander Rastorguyev, and Kirill Radchenko in CAR. A 2019 follow-up investigation by the Dossier Center into the CAR case named Prigozhin, Khodotov, Sytii and others connected to M-Invest, Lobaye Invest and related firms, and noted Dobronravin had traveled to CAR in 2017. That murder case in CAR as well as the Wagner Group’s alleged involvement in the 2017 beheading of a Syrian national near a major Syrian gas field—and covert mercenary operations in Libya—have raised serious concerns about human rights abuses and violations of international law. A U.N. report released in July expressly referenced the journalists’ killings in CAR, pointing out that legal ambiguity surrounding the Wagner Group’s status and relationship to the Russian state makes it difficult to investigate allegations of wrongdoing.

Leaked company billing records for Prigozhin-related companies M-Invest and EvroPolis indicate that the companies paid for Dobronravin to travel to the Central African Republic’s capital of Bangui as he began exploring the possibility of competing for a coveted spot on the U.N. panel charged with overseeing a longstanding arms embargo against CAR. Documents show that Dobronravin, 58, traveled with three Russian citizens sanctioned by the U.S. for their alleged involvement in deploying Russian mercenaries to CAR, Sudan, Syria, Libya and Ukraine. Three years after Dobronravin traveled to Africa with them, American authorities sanctioned all three men, blacklisting Sytii, Khodotov and Kuzin for their alleged ties to another Prigozhin linked firm, Lobaye Invest. Along with M-Invest, EvroPolis and a Sudan focused Russian mining company sanctioned by the U.S. called Meroe Gold, Lobaye Invest is one of several Prigozhin linked shell companies said by U.S. authorities to be involved in exploitative mining operations in Africa.

In July, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned M-Invest, Meroe Gold, and the firm’s chief officer, Mikhail Potepkin, for alleged dealings with Prigozhin. Three months later, in September, Treasury officials also blacklisted Sytii, Kuzin, and Khodotov, indicating in a public statement that all three had allegedly been involved in Prigozhin’s business dealings in CAR.

Dobronravin’s initial appointment capped a lengthy campaign by Dobronravin and several of his well-connected backers to secure an influential role at the U.N. even as he continued to correspond with and consult regularly with U.S. sanctioned individuals. In December 2017, for instance, leaked emails indicate that two months after Dobronravin’s trip to CAR and a short time before his U.N. appointment, Dobronravin sent Sytii a map detailing “influence zones of armed groups” in CAR. In a Jan. 31, 2018 leaked email Dobronravin sent to Kuzin marked with the subject line “RE: Food in Sudan,” Dobronravin included a Russian translation of a news article noting reports that CAR’s president, Faustin Archange Touadera, cut a deal with Sudan’s Bashir to allow Russian mercenaries to train hundreds of CAR soldiers in Sudan. In fact, the contents of hundreds of leaked emails from Dobronravin to Sytii, Kuzin and several other Prigozhin business associates during the 2017-18 period would appear to suggest that Dobronravin was quite aware of his interlocutors’ keen business interest in keeping abreast of political and security affairs in CAR and Sudan.

Dobronravin, according to leaked emails, sought help with an unsuccessful initial bid for a position on the U.N. panel for CAR from Mikael Vadimovich Agsandyan, Russia’s deputy director of the department of international organizations at the Russian ministry of foreign affairs. Like Dobronravin, Agsandyan has long worked on African affairs for Russia, according to a biography of Agsandyan posted on the website for the Center for Energy and Security, a Moscow-based think tank and research center that primarily serves as a policy advice arm to ROSATOM, Russia’s nuclear energy authority. In 2018, Agsandyan, who is in charge of managing the U.N. sanctions portfolio as well as Middle East and North African affairs, corresponded with Dobronravin about the Sudan panel after his bid reportedly became a casualty of U.S.-Russia tensions over Syria and U.S. election interference.

Several current and former U.S. officials who have worked on issues related to U.N. sanctions on Sudan and were asked for their read on Dobronravin’s position said his appointment to a sensitive U.N. post on the heels of consulting for U.S.-sanctioned firms raises questions about whether Dobronravin’s business ties to Prigozhin’s circle were known at the time. “It certainly would be concerning if that connection played a role on the U.N. panel,” said one senior U.S. diplomat, who spoke on condition of anonymity, “But at the same time it would not be surprising if Russia tried to insert a stalking horse on the panel.”

The U.N. Security Council Affairs Division administers the recruitment and vetting of panel experts. A U.N. spokesperson confirmed in response to an email query that Dobronravin had twice applied unsuccessfully for panel positions but added that competition to gain a seat on U.N. panels is often very intense.

The leaked documents pertaining to Prigozhin’s business networks were obtained by the Dossier Center, a London-based investigative research center known for its aggressive scrutiny of corruption in Russia and ties to Russian dissident and vocal Kremlin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky. The Daily Beast, The Guardian, Dossier Center, and New America, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, reviewed the documents as part of a joint investigation.

Dobronravin told a Guardian reporter that he could not “confirm or deny” whether he had ever met Prigozhin. In an email response to queries about his consulting work, Dobronravin did, however, confirm that he traveled to CAR in 2017, saying that a “university colleague” invited him to do a short-term stint in CAR because of his knowledge of the region. Dobronravin also acknowledged that he knew Sytii, saying he had met him during the trip to Bangui. However, travel billing records for EvroPolis and M-Invest show that the companies paid for Dobronravin’s travel to and from St. Petersburg to Moscow on the same train as Sytii as well as an outbound flight from Moscow to Bangui with a stopover in Doha and an inbound flight back to Moscow with stops in Nairobi and Dubai in late September 2017. Records indicate Kuzin and Khodotov were also on the same trip.

Dobronravin in an emailed response to Daily Beast queries about his connections with firms and individuals linked to Prigozhin equivocated on whether he was aware that a trip he took to CAR was at least partially financed by two U.S. sanctioned companies linked to Prigozhin. “During my consultancy work I met or might have met some of the people you mentioned. However, I did not interview these people, and they did not introduce themselves in detail,” Dobronravin wrote.

Yet, leaked email records reviewed by The Daily Beast indicate that Dobronravin was in regular contact with several Russian citizens implicated in the Wagner Group’s operations in CAR and Sudan throughout the 2017 to 2018 period as he first made one bid then another to join the UN as an expert for hire. In a January 2018 email to Alexander Kuzin, Dobronravin sent a Russian translation of a U.N. report on CAR sanctions and indicated he was also sending a diagram of the “EU mission in CAR in 2018,” and information about CAR’s conflict near the Chad border. The leaked email was just one of dozens reviewed by the Daily Beast that appeared to indicate that Dobronravin was well-acquainted with Kuzin, Potepkin, Sytii and others in Prigozhin’s African business networks. At least one email to Kuzin containing a translated news digest indicated that Dobronravin was aware of their interests in Russian mercenary operations on the continent.

It is not alleged that there is evidence that Dobronravin has engaged in any wrongdoing or peddled Russian state interests under cover of his work for the U.N. but rather that his other professional connections exposed in the leak raise questions about whether he is without conflicting interests and is a fit and proper person to sit on a U.N. panel of experts for a part of Africa where Russian interests are increasingly in play.

Russia’s efforts to expand its influence in Africa has raised considerable anxiety in Washington in recent years, but the scope and scale of the Kremlin campaign via arms transfers and mining and energy contracts is still not well understood. As one senior American diplomat put it upon learning of Dobronravin’s connection to Prigozhin’s networks, Washington’s national security agencies have struggled to build a coherent response to Russia’s efforts to cultivate strongman governments in Africa. American national security agencies “have a strategy but there’s no direction,” the senior U.S. diplomat said. “We’re a bunch of amateurs running around. The State Department is in a state of disarray.” If the U.S. is to get on top of the situation, the White House will need a significant strategy shift when President-elect Joe Biden takes over.