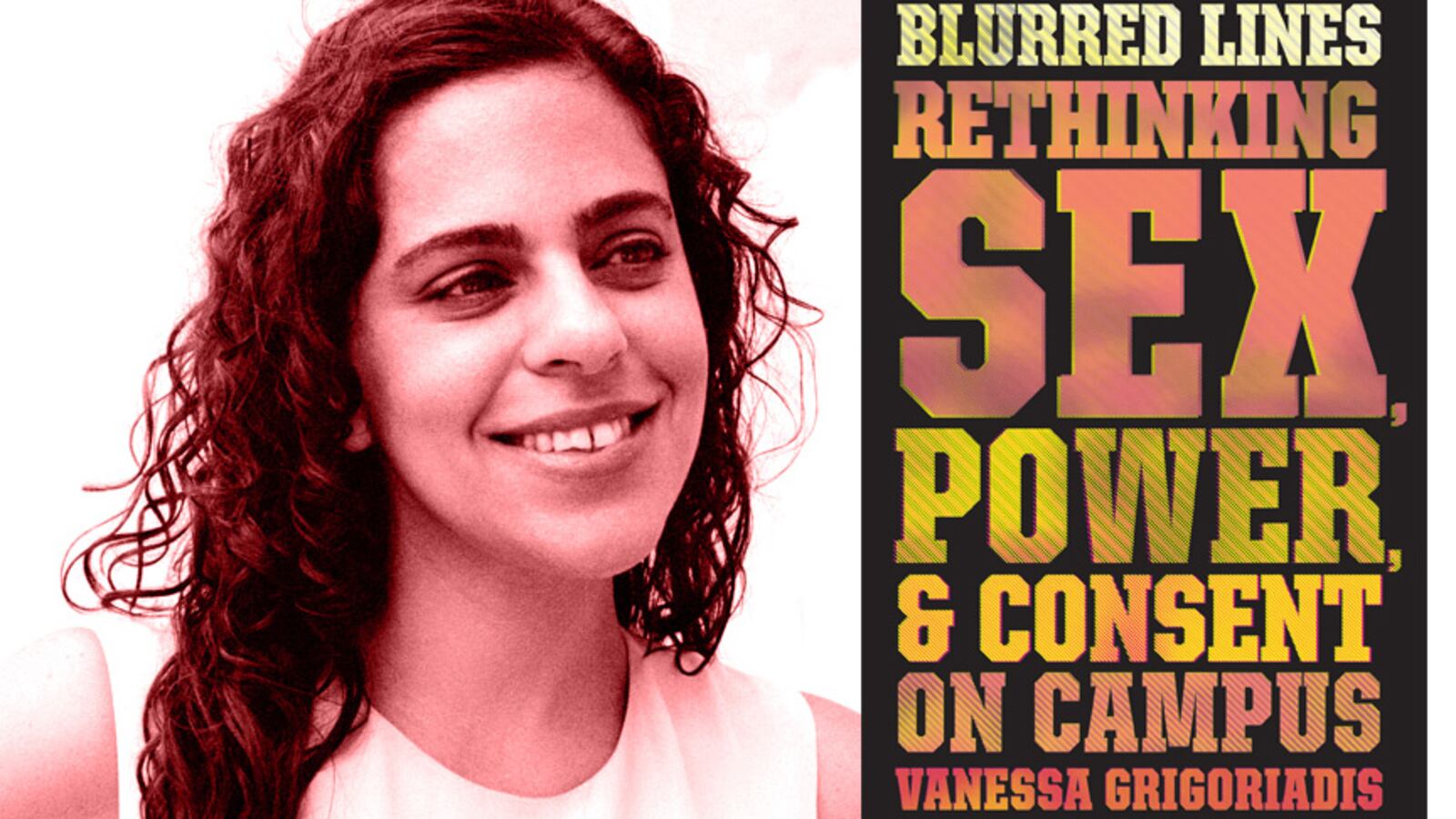

Vanessa Grigoriadis might have expected that her book, Blurred Lines: Rethinking Sex, Power, & Consent on Campus, would be controversial. It’s an immersive and nuanced portrait of the fraught sexual politics on college campuses today, after all.

Grigoriadis, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine, first waded into these politically and culturally choppy waters with a 2014 New York magazine feature about campus sexual assault and spent the next three years researching the issue for Blurred Lines.

She interviewed 120 students from 20 universities, as well as nearly 80 administrators and experts, and pored over dozens of case reports, surveys, and studies on campus sexual assault.

But Grigoriadis could not have anticipated that a book examining the heated debate surrounding consensual sex between college students would kick off a very public, very heated debate between herself and another journalist.

Less than two weeks after it came out, Blurred Lines and its reception became a fully fledged media controversy after writer Michelle Goldberg alleged that Grigoriadis bungled her facts in a scathing New York Times review.

Grigoriadis was equally harsh in her response, arguing that Goldberg, a former Daily Beast columnist, was the one who didn’t have her facts straight.

“After savaging my book, Michelle Goldberg just tried to defend herself on Twitter —and uttered a new set of factual inaccuracies,” Grigoriadis wrote in a Facebook post accusing Goldberg of, among other things, performing “some of her own (incompetent) journalism” in her review.

Turned out she wasn’t wrong: Even before Grigoriadis published her Facebook rebuttal and hit back at Goldberg on Twitter, The New York Times had issued a substantial correction to Goldberg’s review.

The biggest sticking point in Goldberg’s piece was a statistic she attributed to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), a prominent advocacy group, to support her criticism of Blurred Lines.

As Grigoriadis noted in her rebuttal, “of course RAINN did not generate this statistic; advocacy groups do not perform epidemiological surveys. This is journalism 101.”

In its reporting of the media scandal, The Washington Post published several emails from Grigoriadis to editors at the Times objecting to Goldberg’s review.

But the most interesting aspect of this very public skirmish between two celebrated feminist writers is how much it speaks to the complexities of the issues Grigoriadis examines in Blurred Lines, and how difficult it is to cover these issues in an unbiased fashion.

“As someone once said about [Gawker founder] Nick Denton, he’s not passive aggressive, he’s aggressive aggressive. And I’m an aggressive reporter,” Grigoriadis told The Daily Beast in a phone interview last week. “My stories that are blockbusters are not blockbusters because I happen to walk my way into good information in each story that I report. They are blockbusters because I go after the best stuff I can get and I don’t stop until I get it. That’s why I get a reputation for hitting home runs each time. But somehow I was sloppy in my book that I spent three years on?

“I’ve written more than 30 stories that have been among the most-read stories on the websites they ran on when they came out. That’s not an accident. That’s not just luck. That’s the work of an aggressive reporter and someone who really never stops until she gets the job done.”

As for Goldberg, Grigoriadis said, “She helped me with a story once, and we had a cordial exchange. Afterward, I introduced her to editors at New York magazine and tried to arrange coverage of her book. Earlier this year, I sent her a complimentary message because I thought her work in 2017 was fucking awesome. She’s fantastic at what she does. I only ever had respect for her.”

‘My heart wanted to believe almost everyone’

Ever since Vice President Joe Biden described sexual assault at universities as an “epidemic” in 2014—the same year President Obama asserted that one in five women would be victimized during their college years—campus sexual assault has been portrayed as such in the mainstream media and in the 2015 Oscar-nominated documentary, The Hunting Ground.

On the other side of the ideological spectrum, the campus rape “epidemic” was considered a moral panic and one big hoax, like the Rolling Stone gang-rape story.

Refreshingly, Blurred Lines doesn’t adhere to either of these perspectives. Instead, the book examines the ambiguities surrounding nonconsensual sex on campuses with the nuance the subject deserves. It is largely unhampered by ideology.

Grigoriadis admires the new radical feminists who are rewriting the rules of consensual sex on campus. But she also sympathizes with many of the young men who are accused by these women—and harshly punished for crimes they claim they didn’t commit.

“We need to accept that [Danish physicist] Niels Bohr’s principle of great truths may be at work here: situations do exist in which accused and accuser feel they are telling the truth,” Grigoriadis writes. “As much as my brain was skeptical about the people I met, my heart wanted to believe almost everyone, at least those who were telling their own truths.”

Grigoriadis also contextualizes student activism around campus sexual assault within a broader progressive culture on college campuses. The prevailing ideology of this culture is intersectionality, the belief that a person with multiple minority identities is more socially oppressed than an individual with one minority identity.

Students within this culture celebrate “wokeness,” or the state of being socially conscientious. They police culturally appropriating Halloween costumes, and believe that “trigger warnings” should be on the syllabus for a class in which one might have to read about the rape of Daphne in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Grigoriadis doesn’t deny that her own biases and politics inform the takeaway from her book.

“I believe in a lot of the radical rhetoric that these women are using, and I was so excited to see it bleed into the mainstream,” Grigoriadis told The Daily Beast. “It forced America to reckon not only with the young American woman’s experience of sex, but of being sexualized and sexually assaulted.”

She also believes in so-called rape culture, the theory that a culture in which myths about rape like “no means yes” normalize violence against women, though she admits the revived 1970s phrase “makes me a little squeamish.”

“The way these young women spoke about sexual assault and their ideology—while very persuasive—didn’t completely sit right with me as a Gen X mother of two,” she said.

Grigoriadis illustrates how we’ve arrived at such a politically charged moment—and it’s not all about student madness. She points out that the bedroom is one area where today’s otherwise fierce, self-confident women have not previously been able to assert power, and still often feel unable to stick up for themselves.

In her book, Grigoriadis explains that Gen X professional women don’t like to trumpet victimhood or think or themselves as vulnerable—and that this perspective allowed her to relate to some of the sentiments expressed with angry mothers of accused boys whom she interviewed.

“That’s where I found an essential difference between these college girls’ views and mine, and that’s where I had to decide whether what they’re doing was good or bad.”

Grigoriadis agrees with the underlying politics and major goals of today’s young activists—she supports an affirmative “yes means yes” standard for consent—and admits as much throughout Blurred Lines.

In most cases, she believes the young women who claim they were sexually assaulted, like Emma Sulkowicz, the Columbia University student who became the face of America’s anti-campus rape movement in 2014 with her senior art thesis, Mattress Project: Carry That Weight.

The marathon performance piece involved carrying a mattress around campus all year to protest the school’s handling of her alleged rape by a fellow student. “I know she hasn’t provided incontrovertible evidence,” Grigoriadis writes of Sulkowicz. “I recognize believing her is a personal choice, and a political one too.”

But she also expresses compassion for those accused of sexual assault. She comes to believe that they, too, have suffered a kind of trauma in the fallout of being branded rapists. One refers to himself as a “survivor.”

“There’s a very primal fear for the accused that a woman can claim he sexually assaulted her, and he cannot prove that she’s wrong,” Grigoriadis told me. “That is a power that women hold over men.”

Blurred Lines argues that one of the biggest roadblocks in tackling sexual assault on campus is the fact that not everyone agrees on what it is.

“Definitions have multiplied, often controversially, to cover a wide variety of problematic sexual behavior,” Grigoriadis writes, “from luring a classmate into an apartment and locking the door from the inside to a time-tested dodge (‘I’ll only put in the tip’) to even a sexist, objectifying remark (‘Nice ass!’).”

Definitions of consent also vary widely on campuses. While the legal definition is largely accepted, the standard that many progressive students are advocating for is much murkier.

“I’m not so politically progressive that I would use the word rape to describe anything that wasn’t penetration,” Grigoriadis told me. “But when a guy tries to enter a woman’s body with a part of his body, he should be sure that the other person has agreed to it and not just coerce her to have sex because that’s what a ‘real man’ does.

“That’s a tricky situation because the law doesn’t say that kind of coercion is rape. But I just don’t understand how anyone can argue that there shouldn’t be consent in that situation. It doesn’t have to be conveyed in some of the stupid terms that colleges are using—‘enthusiastic consent!’

“We all know that people are more ambivalent than that. But if a woman signals that she doesn’t want it, don’t make her have it. Consent is not only about desire. It’s also about your will not being overrode and being worn down by coercive speech.”

‘There are so many rapists on this campus, and you never know who is one’

Grigoriadis’ book arrives at a time when the culture around campus sexual assault has arguably never been more progressive. In this new campus culture, feeling traumatized by a sexual experience and believing that it is assault means it is assault.

Robin Thicke crooning “I know you want it/but you’re a good girl” and other song lyrics implying “no means yes” are no longer acceptable. (A 2013 Daily Beast headline about this song—“Robin Thicke’s ‘Blurred Lines’ Is Kind of Rapey”—would be considered an understatement today). And the idea that how a woman dresses informs whether or not she’s “asking for it” is positively arcane.

A pop culture connoisseur, Grigoriadis convincingly illustrates how today’s new radical feminists on campus see themselves in celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Beyoncé, who sell their sexuality and call it empowerment feminism.

“Middle-aged handwringing about young women denigrating themselves as sexual playthings misses that this is their answer: Wearing whatever they want, talking and acting as raunchy as they want, but also establishing new rules about sex and calling out boys who don’t treat them right,” she writes. “They strive to take charge on all fronts.”

Much of Grigoriadis’ research was conducted at Wesleyan, a small, private, hyper-progressive university and Grigoriadis’ alma mater (it was known as PCU—“Politically Correct University”—back in her day), and at Syracuse University in upstate New York, a larger school that is less progressive when it comes to the issue of campus sexual assault.

Indeed, students’ attitudes about sex at Wesleyan differ drastically from those at Syracuse.

At Wesleyan we meet Chloe, a senior and sexual assault survivor whose attitude about consent exemplifies progressive politics on campus today.

To Chloe and her friends, a legal sexual encounter might still be considered assault. “There’s a difference between illegal and unethical,” Chloe tells Grigoriadis. “Life is not about doing whatever you can do. It’s about not doing what is traumatic to another person.”

Chloe and other anti-rape activists at Wesleyan have little regard for due process. They care more about changing the culture than changing the laws. Strolling around campus one day, one of Chloe’s friends remarks that “there are so many rapists on this campus, and you never know who is one—people are multifaceted, man.”

Grigoriadis is somewhat baffled by this observation; certainly, it’s not something any of her most progressive peers at Wesleyan would have said when she was a student there. And it would induce eye rolls from many of the women she interviewed at Syracuse University.

One Syracuse student who refers to herself as “Blackout Blonde” recalls some of her sex-capades to Grigoriadis, including an incident that the rad fems at Wesleyan would surely argue was sexual assault.

But “Blackout Blonde” doesn’t consider herself a survivor.

“As far as I’m concerned, there’s only one person to blame in that situation, and his name is José Cuervo,” she says.

There’s a cognitive dissonance here for readers who aren’t radicals or millennials entrenched in this new culture. Ten years ago, I was a student at a university where getting drunk and having vague memories (or no memories at all) of a sexual experience was practically the norm, for both men and women.

Much like Grigoriadis, though, I began to look back on some of my sexual experiences anew while reading Blurred Lines. And while I didn’t suddenly convince myself that I’d been assaulted (nor did Grigoriadis), I realized there’s a good chance I’d see it differently were I a student at a school like Wesleyan today.

This is one of the reasons the book succeeds so much: Embedded with Grigoriadis on college campuses, readers are forced to re-examine their own sexual experiences. Grigoriadis illustrates how we’ve arrived at such a politically charged moment—and it’s not all about student madness.

But she recognizes that some students’ actions and belief systems are very “snowflake-esque,” she said. “Students who are too invested in the notion of trauma give strength to the arguments of the conservative right and to feminist scholars like Laura Kipnis.”

In her 2017 book Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campuses, Kipnis argues that the progressive belief system around sexual assault often obscures sexual realities and ambivalences, to the extent that cases of unwanted or ambiguous sex end up being labeled sexual assault—sometimes years after the fact.

Grigoriadis agrees that an obsession with trauma can devolve into melodrama. “But we also know that sexual assault does create trauma,” she said. “That’s not up for debate, so we can’t just say it’s all melodrama.”

Blurred Lines argues that while the campus adjudication system is flawed, the bigger problem is that young women are not adequately educated to avoid putting themselves in danger of sexual violence, and that young men are raised to believe that all girls want to have sex with them.

“A lot of the cases we’re talking about don’t involve physical violence,” said Grigoriadis. “More often, they’re cases where a guy has sex with a woman who is passed out drunk and he figures, ‘She came home with me and passed out, but I still get to have sex with her.’”

Blurred Lines devotes considerable attention to role of alcohol consumption in campus sexual assault; Grigoriadis argues that it is the the biggest common denominator in most cases.

“We have a confusion over what consent is and situations where women are having sex that they feel violated by and the man is expelled because consent wasn’t clear, even though he truly doesn’t believe he did anything wrong,” she told me.

“There are a lot of sticky situations. On the one hand you say, ‘She was offering it up.’ On the other hand, those guys should have recognized that this girl was so wasted she wasn’t in a good place to have sex with. Even if she’s aggressively coming at them, they should recognize that she’s not in her right mind. That’s where it comes down to individual responsibility.”

‘We are in the midst of a vast social change about what is ethical in the bedroom’

Grigoriadis’ public row with Goldberg was still percolating when, last Friday, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos announced long-anticipated changes to federal guidelines on campus sexual assault, effectively rescinding the Obama administration’s 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter that outlined how universities should respond to sexual violence.

The Obama-era guidelines “created a system that lacked basic elements of due process” for the accused and “failed to ensure fundamental fairness,” DeVos said in a statement Friday.

While the Obama-administration regulations mandated that colleges apply a “preponderance of evidence” standard to sexual misconduct cases—the lowest burden of proof at roughly 51 percent likelihood of guilt—the new interim guidelines allow schools to apply a higher “clear and convincing evidence” standard (PDF).

Advocates for the accused have cheered the interim guidance as a sign that the government is taking their due process concerns seriously. But victims’ advocates argue that the new system will allow universities to sweep campus sexual assault under the rug once again, and will discourage victims from reporting sexual violence.

One aspect of the OCR’s interim guidance that Grigoriadis supports is giving universities a choice to decide whether to allow both the accused and the accuser to appeal—or just the accused. “The accuser shouldn’t have been able to appeal,” Grigoriadis said, referring to Obama-era guidelines.

“I’m in favor of low punishments for boys who have committed offenses that sit on the line of consensual and non-consensual. We are in the midst of a vast social change about what is ethical in the bedroom, and those boys are caught in the time of transition,” Grigoriadis told me. “And I think they should be rehabbed, not spun out of school so they can sit in their parents’ basement and post about how much they hate women on Reddit. So on the face of it, mediation between parties—which is in the new guidance—could be a step in the right direction.”

All things considered, Grigoriadis doesn’t believe that DeVos’s changes will have a long- or short-term effect on the issue of campus sexual assault.

“A teeny-tiny number of campus tribunals occur across the country each year; the notion that college boys are being brought up on rape charges by SJWs as often as they go to soccer practice is a myth,” she said. “Whatever standard of proof that teeny-tiny number of tribunals use is not going to stop the movement of millennial women to put down their foot about their sexual autonomy, from violent rape, and to minor sexual misconduct.

“Women have accepted that stuff for so long. Isn’t it kind of awesome that these 21-year-olds are putting their feet down? I’m not going to say that everything is cool here or that I don’t see problems in their approach, but I do think it’s coming from a place of social progress.”