In the closing weeks of March, comics pages in daily newspapers were oblivious. People were still making plans. There were parties. When animals talked, as animals in comics do, they said nothing about quarantines.

One of the first voices to speak of the new normal belonged to Barry Taylor Wilkins, the younger of two brothers in Ray Billingsley’s long-running strip “Curtis.” It was on Monday, March 30, and we see Barry and Curtis’ mother, Diane Wilkins, squeezing hand sanitizer on her boys’ hands.

“Why do I have to put this stuff on my hands, Mommy?” asks Barry.

In “Curtis,” it is common for such questions to have both simple and complex answers. Since debuting the strip in 1988, Billingsley has mixed lighthearted gags with occasionally stark portrayals of the Wilkins, a middle-class African-American family, and their larger community of family, friends, barbers, and teachers. In “Curtis,” realism sneaks up on you: the family’s third-floor apartment can feel cramped; the father, Greg Wilkins, is uninspired by his job; and young brothers Barry and Curtis have real stresses, like fear of guns in school.

On this day, Curtis tells his brother the sanitizer is to clean his fingers before picking his nose. But we know the real reason. So does Diane. The boys don’t. But that will change.

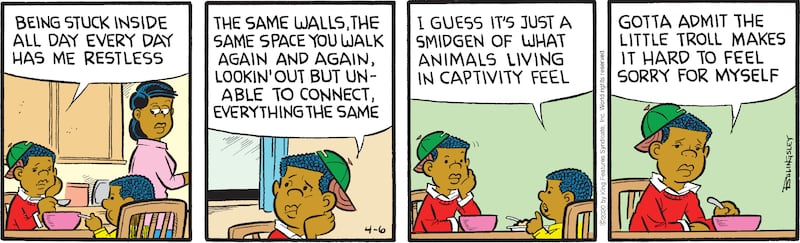

At four panels a day, time moves slowly in a daily comic, even when events in other newspaper pages move alarmingly fast. As March finally gave way to April, the Wilkins family were seen adapting to their little corner of the pandemic. There are jokes about home-schooling and cabin fever. Greg tries to cheer his sons up with a theatrical display of pancake-making, flipping them with a juggler’s flare. “I try my best to shield my boys,” Greg will say to Diane. “And that is why I love you always,” thinks Diane.

Then, in the middle of breakfast, the Wilkins’ lives change again. Curtis receives a phone call. He walks back into the kitchen, dazed. His stack of pancakes is still waiting for him, untouched.

“It’s our teacher, Mrs. Nelson,” Curtis says. “She tested positive for coronavirus.”

“I don’t want to start much trouble, but sometimes I can’t help myself,” Ray Billingsley told me in a recent phone interview from his home in Stanford, Connecticut, where he has been hunkered down with his basset hound, Biscuit. “It’s the artist in me.”

Ray Billingsley, the author of Curtis

Courtesy Ray BillingsleyAlthough a few new comics starring people of color have debuted in recent years, “Curtis” remains one of the few daily syndicated strips centered around black characters. Billingsley sees himself following in the tradition of Morrie Turner’s “Wee Pals” and Ted Shearer’s “Quincy”—and also Aaron McGruder’s “Boondocks,” but with a difference. “‘Boondocks’ was in your face, and he didn’t care how much,” Billingsley said. “The rest of us, we have to walk a tightrope.”

Billingsley tested that tightrope when the Wilkins family noticed that Barry was slipping milk out of the house. They thought he was feeding a cat but followed him and found instead an abandoned baby. In another strip, Diane miscarried after being assaulted at an ATM. “Nobody was expecting a miscarriage in ‘Curtis,’” Billingsley said.

One of the slyest moments in “Curtis” happened when the Wilkins family and friends were invited to Dagwood and Blondie Bumstead’s house, as part of a celebration of the 75th anniversary of the comic strip “Blondie.” They took a wrong turn and ended up in Mary Worth’s neighborhood. There, they discovered how fast police response time can be in a different part of town.

Billingsley often pushes against his six-week deadline to allow him the chance to comment on current events. Yet the experience of drawing “Curtis” during COVID-19 feels different than anything he has done before. “This one I’m going by instinct. I said, ‘It’s time to do it right now.’ I kept seeing that nobody was addressing this.”

I asked if he felt a special weight in his decision to have a character contract the illness. “Actually, I’ve been feeling the weight of this entire story,” he said. “I have to really get into what everyone was feeling. We’re talking about a core of four people and how it’s really affecting them as a unit. I’m not showing anyone else. It’s just about this family right now.”

“This has been one of the harder ones to draw. I had the flapjack party going on and I knew something was going to come up. When Curtis comes into the room, it hit me then, too. It made me depressed. I do it to myself. They’re so much from the heart that they can hurt me first. If I’m hit on an emotional level, I’m pretty sure other people will be too.”

People don’t usually die on the funny pages. It’s only possible in what’s called a “continuity” strip, one in which a narrative might stretch over many days or weeks. After all, Beetle Bailey can get beaten to a pulp and spring back up the next day, and nobody questions it. “In Beetle’s world, it doesn’t matter who’s president, or what kind of disease is going around,” laughed Billingsley, who counted the late “Beetle Bailey” creator Mort Walker among his friends.

The first major character to die in comics was Mary Gold, who in 1929 contracted a mysterious illness in the comic strip “The Gumps.” Since then, deaths have remained rare. In 2004, it came for the elderly Phyllis Blossom Wallet in “Gasoline Alley.” Garry Trudeau’s “Doonesbury” has featured several deaths, most controversially that of Andy Lippincott, who died of AIDS in 1990. Letters from readers poured in after the death of the family dog Farley in Lynn Johnston’s “For Better or For Worse.”

You didn’t see any death scenes in the comics page during the so-called Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918. Comics scholar Jared Gardner began searching through hundred-year-old newspapers for any comics that dealt with the outbreak and was surprised by how little he found. “Lots of words, lots of typing, but not lots of drawing,” Gardner said, speaking via Zoom from his home in Columbus, Ohio, where he serves as director of Popular Culture Studies at Ohio State University.

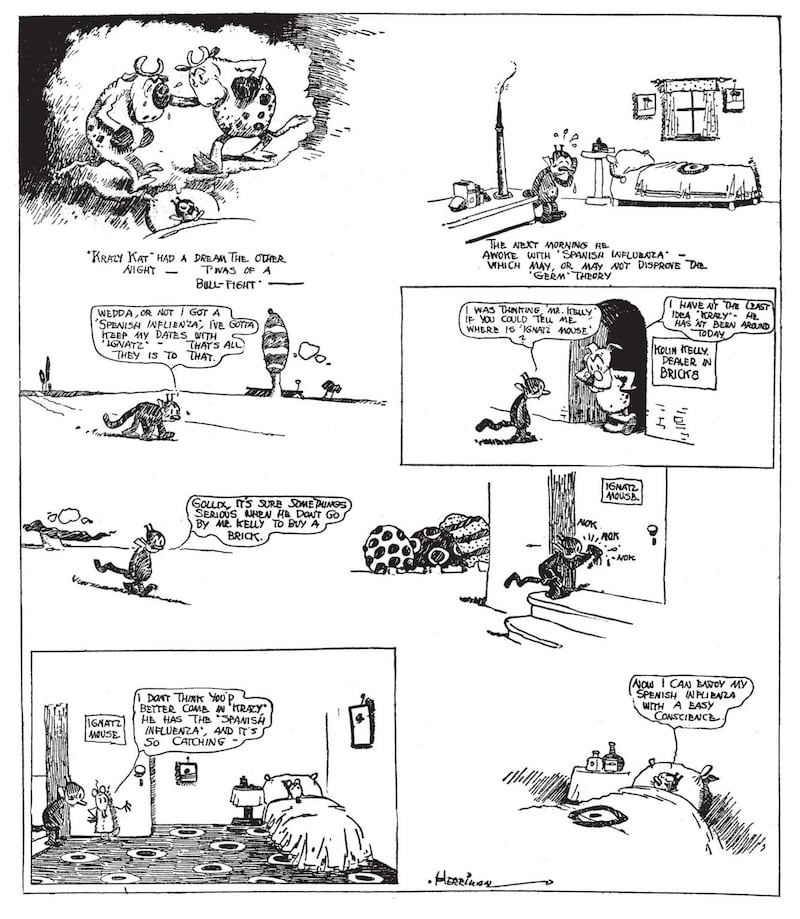

Gardner put what he did find on his website “Drawing Blood,” which is dedicated to comics and medicine. There is a single Bud Fisher “Mutt and Jeff” comic with the punchline “I went home last night and opened the window and in flew Enza.” A few comics discuss wearing masks and avoiding crowds. Some subscribe to the xenophobia suggested by the misnamed “Spanish flu.” Others lightly mock it, as in George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat,” in which Krazy dreams of a Spanish bullfight and wakes up the next morning with the flu, which “may or may not disprove the ‘germ’ theory,” as Herriman wryly notes.

Gardner suspects that the oversized cultural influence of comic strips in 1918 might be why there were so few mentions of the flu. Cartoonists and their bosses knew they were being watched. As John M. Barry wrote in his history The Great Influenza, the Sedition Act promised jail time for anyone who dared “print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the government of the United States.” This even extended to “pessimistic stories,” and the trial of leftist cartoonist Art Young for violating the Espionage Act had proven that the government reach might extend to cartoonists.

It might have just been that most cartoonists didn’t think people wanted to see the flu in the funnies. Still, the few that did address it have a lesson to teach us. “It must have felt like the end of the world for these folks as surely as this time does for us,” Gardner said. “It can feel unprecedented and apocalyptic, but looking at comics from a hundred years ago reminds us that they got through it.”

The first widely syndicated newspaper comic to address COVID-19 was Bill Hinds’ “Tank McNamara,” a sports-themed strip that had to contend with the sudden absence of professional sports. “Curtis” followed shortly after. Cartoonist Stephan Pastis often makes himself a character in his smart and acerbic “Pearls Before Swine”; he drew his first coronavirus comics as if he were stranded with nothing but pencil and notepaper, playing off his real-life situation of being out of the country when the United States starting limiting travel. Meanwhile, a heartbreaking series in Darrin Bell’s “Candorville” tackled social isolation by showing full-panel cityscapes from throughout the world. The same thought arises in different languages from each house and apartment: “I am all alone.”

Argentinian cartoonist Ricardo Siri, whose comic “Macanudo” is published in English under his pen name “Liniers,” says the strip was born out of time of social and economic crisis in Argentina. “My way of being punk was to be optimistic,” he said, talking to me by phone from his current home in Vermont, where he teaches at Dartmouth College. His coronavirus-themed work has been delicate and hopeful, often turning to the natural world for inspiration. In one full-panel strip, a girl and cat sit together, watching a butterfly make its way across a grassy field. The caption reads: “Taking care of each other will also be contagious.”

“I feel like when people are drowning, you can either throw them a life vest or an anvil,” Siri said. “Every now and then I allow myself to be angry in the strip, or pessimistic, or nihilistic. But I think the reason the comics page first existed, from the Pulitzer and Hearst years, is to give people something so they don’t jump out the window.”

In a sense, the visual representation of COVID-19 is itself a cartoon—a multi-colored illustration of a spike protein-studded ball created by Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (By contrast, Gardner notes that cartoonists in 1918 often used mosquitoes to represent the flu, due to the insects’ past association with sickness and death.) Eckert told The New York Times they were tasked with creating “an identity” for the coronavirus. But it took cartoonist Mark Tatulli to turn their image into a full-blown character. In Tatulli’s wincingly funny “Lio,” the Coronavirus might laugh menacingly or wait quietly in a doorway. In one chilling comic, it sits on the couch, watching the news. “It’s always weird seeing yourself on TV, ya know?” it says to a child.

To Gardner, these novel approaches to the novel coronavirus are a sign of hope for comics themselves. “If you want a media that can talk about it right now, and both comfort and educate, what does it better?” he said. “There’s social media, which is evil, and there are comics. It’s a moment where the comic strip, editorial cartooning, and web comics can talk about stuff as it’s happening, and they can build space for community in the moment—which is part of why comics and cartooning became so important in the first place.”

Added Gardner, “There’s a tone, a kind of intimacy, that the comic strip can capture that is really needed. I’m grateful for it.”

The most intimate moment in the current run of “Curtis” comes when Greg Wilkins is explaining to his son that because of social distancing, he can’t visit Mrs. Nelson in the hospital. Curtis pumps his fist and says, “Awwww, she’ll be all right!—Mrs. Nelson is a tough ol’ lady.”

Greg smiles and holds his son. He praises him for his positive attitude. What he doesn’t see—but what is clearly visible to readers—is that Curtis is crying.

I told Billingsley that this devotion of a student to a teacher reminded me of a series in Charles M. Schulz’s “Peanuts,” when Linus is watching his beloved teacher Miss Othmar during a teacher’s strike, and she falls down with exhaustion.

“Remember, only Linus was close to Miss Othmar,” says Billingsley. “Lucy wasn’t. It can be a very special bond between a student and a certain teacher.”

In fact, he said, Mrs. Nelson was the name of his own third-grade teacher. “I didn’t have the best home life, growing up. I had a father who was very strict. It got to the point where I looked forward to going to school, because I was away from my father. I was one of those weird kids who was good friends with the principal.

“Mrs. Nelson was the first person who told my parents I had a career in artwork. She encouraged me, and from that time on I kept drawing.

“So when Curtis put his head behind his father, I quietly cried to myself, because I knew I was going to do this.”

Since that moment, there have been jokes in “Curtis” about Curtis saying that he’s bored and being handed a mop and bucket, and of Greg admitting to his son that he misses “being at work complaining about being at work.” But Billingsley said he’ll be returning to the story about Mrs. Nelson. He doesn’t know exactly when. Just like when it started, he said, he’ll be going by instinct.

“When it’s time to wrap this story up, I’ll know it.”