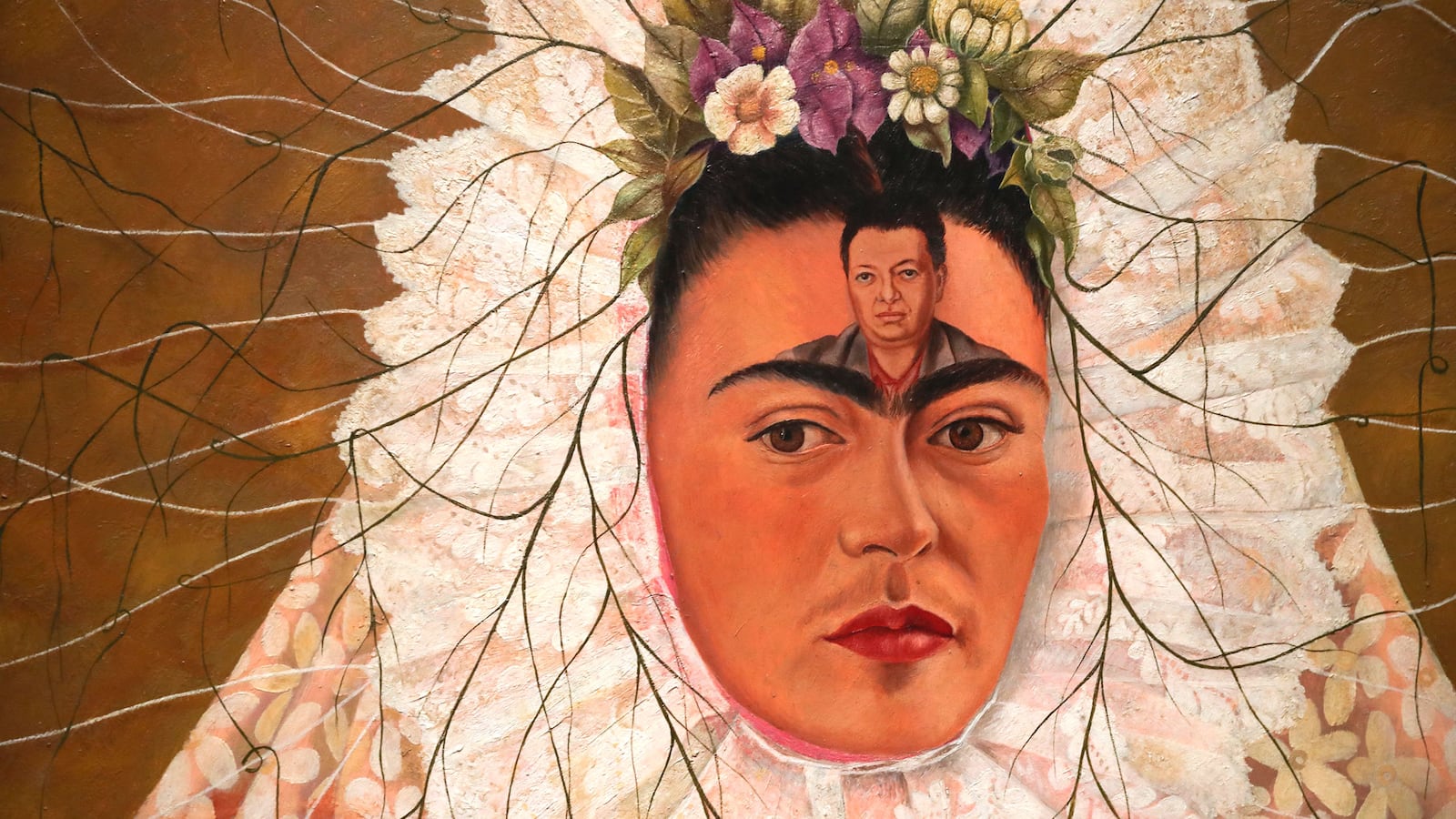

LONDON—“Kahlo’s unique approach to fashioning her self became both a source for and subject of her bold, uncompromising art,” reads a placard at the entrance to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new exhibition in London, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

On display here, and exhibited outside of Mexico for the first time since they were discovered in Kahlo’s home in 2004, are some of the most intimate possessions of Mexico’s best-known female artist, including objects of dress. Informed by her mixed heritage, Kahlo’s vibrant personal look was as statement-making as her works of art.

Circe Henestrosa, co-curator of the show, is responsible for bringing the idea to London.

An upside down image of Kahlo opens the exhibit. In it, Kahlo lies sleeping in bed, dressed in a striking black-and-white traditional, embroidered design, her head resting on white pillows. The image is doused in blue light which gives visitors the idea of visiting the blue house, or Casa Azul, her Mexican home where the pieces were first displayed.

The photo of Kahlo in bed is the first of more than 200 objects on show. The idea is to cast new light on Kahlo. “A counter-cultural and Feminist symbol, this show offers a powerful insight into how Kahlo constructed her own identity,” co-curator Claire Wilcox says.

Personal artifacts also on display, which were until recently sealed in her home by husband Diego Rivera for 50 years after her death, include her vivid make-up: the brow pencil she used to create her famous arched look; her favorite Revlon lipstick; and red nail polish.

Additionally, 22 colorful Tehuana dresses, pre-Columbian necklaces, and some of the hand-painted corsets that made up her “carefully choreographed” look are featured.

Born near Mexico City in 1907 to a German father and a mother of Spanish and Indian descent, Kahlo’s family taught her about style from a young age. Early photographs of her family feature women wearing traditional starched lace headdress from the Oaxaca region. Another shows her mother, Matilde Calderón y Gonzalez, wearing some of the European fashions that were popular prior to the Mexican Revolution.

The ways in which Kahlo’s disabilities informed her work is a major theme of the exhibit.

“When [Kahlo] was six, she had polio, leaving her right leg significantly shorter than the other,” Henestrosa tells The Daily Beast. “She would wear five or six socks to level her legs, and started wearing long dresses, establishing a relationship between her injured body and dress.”

Kahlo had intended to become a doctor, but started to paint after she was impaled and became bedridden from a bus collision when she was 18.

As her love of art grew, she even explored photography with her father who was a photographer. She learned from him a fastidious attention to detail and inherited his love for self-portraits. She lived at a time when selfies had to be painted, and paint them she did. Many of the self-portraits she painted when bedridden are featured in the exhibit.

After her accident, “[Kahlo] would cover her body under these beautiful fabrics but she would uncover it through art very bluntly,” Henestrosa says.

“This [was] the beginning of the career of a wonderful artist,” Henestrosa adds. “But also the beginning of the deterioration of her body.”

Some of the orthopedic corsets she wore and decorated are on display, alongside her prosthetic leg which she bore after hers was amputated.

The exhibit also explores her personal life, often through the lens of style.

Kahlo married fellow artist Diego Rivera at the age of 22. The two met through photographer Tina Modotti, a fellow Revolutionary, after Kahlo joined the Communist party in 1928.

They divorced a decade later in 1939 and remarried in San Francisco in 1940. She once said of their stormy relationship, “I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. The other is Diego.”

Still, they did much together. One of the black-and-white photographs on display shows Kahlo marching in a Union parade for technical workers and sculptors, wearing a stylish suit. She has a Communist cap in hand.

Kahlo was often featured in her husband’s paintings. In Rivera’s Ballad of the Proletarian Revolution, Kahlo wears a red shirt with a Communist star as she hands out weapons.

But was she revolutionary in style?

“At the time, she wanted to look very Mexican. Promote Mexican and indigenous cultures and values,” says Henestrosa. “She wanted to promote her political beliefs. She was a Communist.”

Kahlo was introduced to the U.S. on a work trip to San Francisco with Rivera in 1930. She referred to the country as Gringolandia. Still, her style made a distinct impression on the Americans and she was invited widely to events. Some of her looks are on display.

As such a multi-faceted figure, Kahlo’s specific style is difficult to pin down.

“I would describe her style as hybrid, unconventional and unique,” Henestrosa. “At the time, people were not wearing this ethnic dress. They were inspired by Europe and the U.S. so it was different.”

A self-portrait from 1932 shows Kahlo wearing a pink dress, coral necklace and lace gloves. In contrast, in a painting that was originally featured at an exhibition of Jewish portraits in New York in 1933, she looks suave with her glossy hair pulled back in a bun, a velvet jacket, lace gloves and her signature coiffed eyebrows.

Visitors can examine her style further in a series of photographs taken by the French photojournalist Gisele Freund. Freund spent two years in Mexico, photographing artists and writers. She took many photographs of Casa Azul, Kahlo’s home, which became a “Microcosm of Mexico’s rich and multilayered cultures.”

One of her portraits from 1952 shows Kahlo in her garden feeding the ducks in a stiff white dress decked in a red shawl, conjuring imagery of the traditional mozzettas historically worn by Popes. In a portrait by Fritz Henle from 1943, Kahlo poses in a chair, wearing a long cotton skirt decked in a striped apron. Her hair is ribboned into a striking shape, and her eyebrows accent her strong cheekbones and swan-like neck.

Several of the actual outfits she wore are on display, including a velvet cape with embroidered ribbon appliqué and two silk bows, paired with a skirt made from French silk. Another outfit in the show is a beautiful regional costume from Oaxaca, which includes a tunic (huipil) and skirt. Kahlo wore variations on this Tehuana dress for most of her life.

An artist in more ways than just a painter, she also made her own jewelry. This includes a chunky gray necklace made of jade and turquoise. The beads were taken from a Mexican burial site. Some of this jewelry tells a story. A pair of her earrings featuring paired birds are thought to have come from a jewelry shop in Mexico City where her parents met.

Some of her looks are rich and traditional. Others are striking and simple. Her personal style highlighted her Mexican heritage, but was clearly interpreted by a bold modern-day woman.

A portrait of Kahlo by Lucienne Bloch, taken in New York in 1933, shows her wearing a simple white cotton top, long black skirt, and hair pulled back. She looks cool and tough.

Her love of traditional clothing also included the Puebla blouse, a loose-fitting smock style blouse with striking embroidery, as shown in a photo by Western. Shawls were another favorite. A photograph of 23-year-old Kahlo in San Francisco shows her in a simple rebozo, or Mexican shawl, paired with chunky earrings. The shot was taken by Imogen Cunningham. One of her European shawls hangs on display here at the museum.

Dreamy music leads to a vast room with a dazzling display of her outfits. In the Tehuantepec style, these brightly colored combinations are made up of long traditional skirts, with lace borders, embroidered blouses, or tunics, and shawls. The pieces are modeled on mannequins created in her image, complete with her braided hair.

A placard in the final room declares that appearances were important to Kahlo to the end. We learn that, when she died, at the young age of 47, a friend dressed her in a traditional white huipil, braided her hair with ribbons and flowers and put rings on her fingers.

As the show concludes: “Today, she remains an object of fascination, embraced both for her fierce individuality and her defiance in the face of adversity. Above all, she is renowned for her self-made image, for making her self up.”