In Western cultures, the idea that gender is fluid rather than binary has come with labels like transgender, referring to people who don’t identify as the gender they were given at birth.

But in South Asian countries like India, where non-binary genders have existed within communities that date back thousands of years, many people who consider their gender to be fluid feel boxed in by modern labels—even as those labels have legally liberated them.

One of those people is Laxmi Narayan Tripathi, who fought to convince India’s Supreme Court to recognize a “third gender” in 2014 (the court concluded that “it is the right of every human being to choose their gender”).

Those who want to identify as a “third gender” can now do so on government-issued documents. Yet Tripathi considers herself “hijra,” the coloquial term for people who are assigned male genders at birth but identify as female.

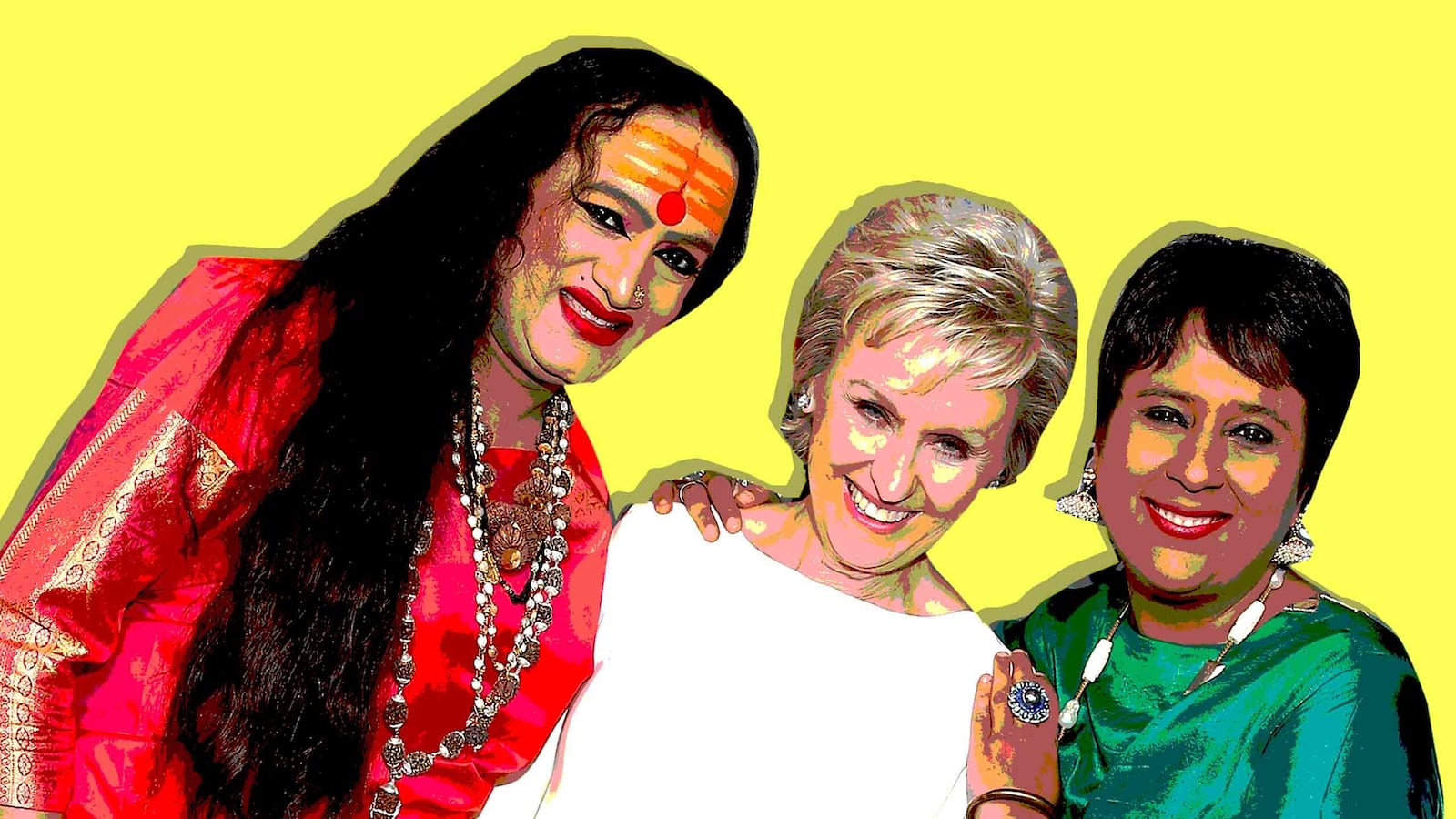

“Hijra is the oldest ethnic transgender community,” Tripathi explained at Friday’s Women in the World Summit in New York, where she was interviewed by journalist Barkha Dutt. “We are neither a man nor a woman, but we enjoy the femininity of the world. We have the power to curse and the power to bless.”

The 2014 Supreme Court ruling was the end of a long campaign for Tripathi, who had been working with her gay friend—unsuccessfully— towards repealing Section 377, the law that criminalizes homosexuality. She is now chair and founder of Astitva Trust, Asia’s first transgender organization.

Dutt remarked that India is a “paradoxical country in more ways than one: we have criminalized homosexuality while recognizing transgenderism.”

“Hijra culture gets away with many things,” Tripathi said with a wry smile.

Yet hijras are still reviled by the mainstream, though Tripathi insists they weren’t marginalized until India was colonized by the British. “We were left to beg and sell our bodies,” she said.

Asked about the anti-transgender bathroom bills in the U.S., which would require transgender people to use separate restrooms, Tripathi said there is “no need for a third bathroom.”

“The transgender person should be able to choose her own bathroom, male or female, wherever she feels comfortable,” she continued. “Instead of dividing society in the name of gender, we should create a society where there should be acceptance.”

In India, she noted that there are now twelve states that provide welfare for individuals who identify as a third gender.

“Change is inevitable,” she said. “But in this present scenario where the political leaders and policymakers are men, we have to come together not only as women but as feminine strength.”