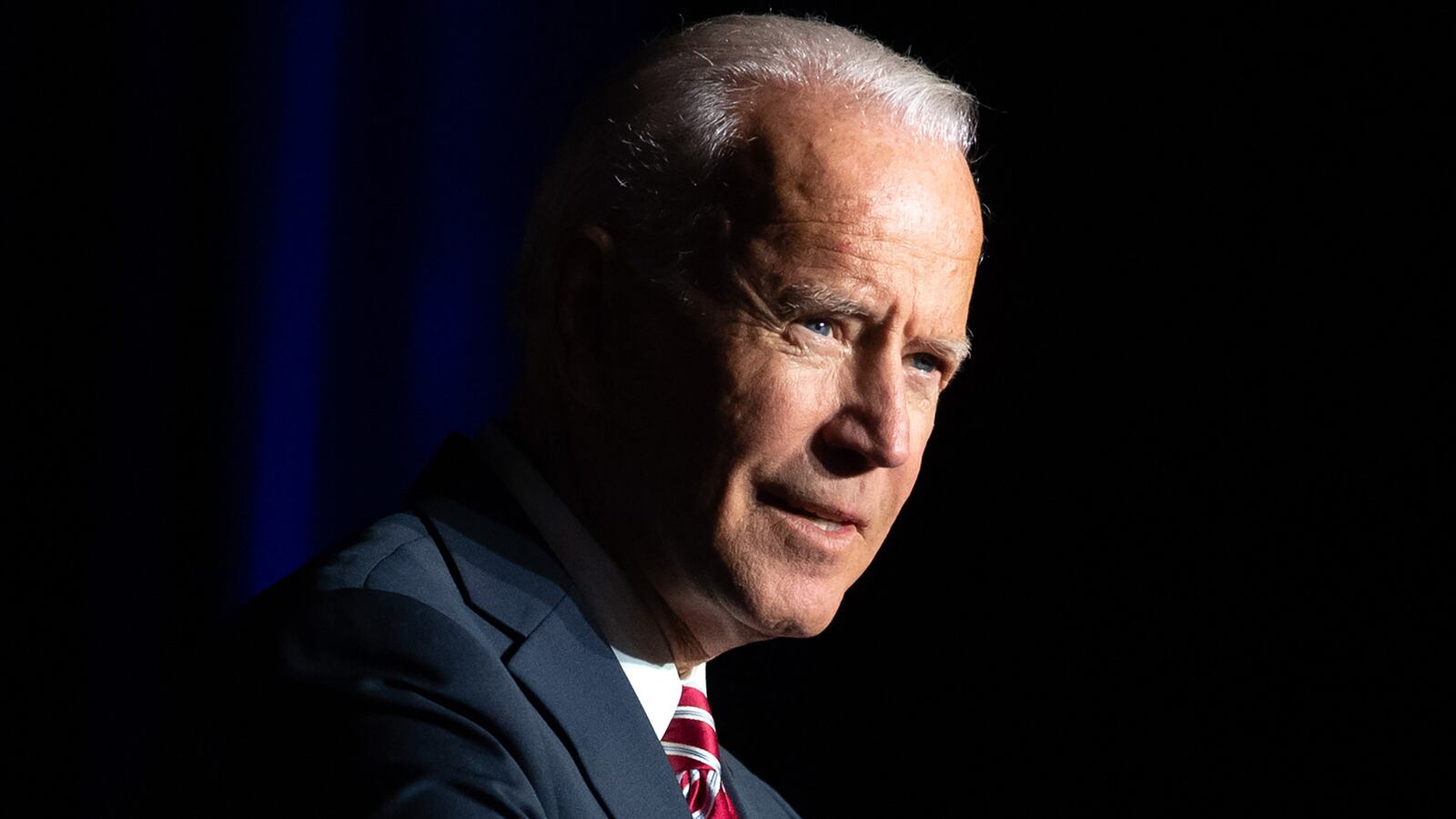

After days of relative quiet, former Vice President Joe Biden announced that he plans to hold daily press briefings, starting as early as Monday from a remote location, as part of a broader digital and communications push as he closes in on the Democratic nomination.

“We’ve hired a professional team to do that now,” Biden said in a teleconference with the press on Friday afternoon, in reference to a question about establishing a foil for Trump’s daily press briefings. “We’re in the process of setting up the mechanisms by which to do that.”

The announcement answers growing questions about whether Biden’s campaign would set up some type of shadow effort to counter President Donald Trump in the age of COVID-19. Those questions, and more specifically, whether they had a plan at all to match Trump’s increasingly erratic press conferences where he routinely contradicts experts, misstates facts, and paints a far rosier picture of a crisis that has upended American life, had gone largely unanswered until Friday.

“The bottom line is everything from providing access to where I physically live and being able to broadcast from there, as well as our headquarters, is underway," Biden said.

The stakes are now higher than ever for the former VP seeking to make both a values-based and tactical contrast to Trump. But as the country grapples with containing the spread of coronavirus, Biden is confronting challenges of a leading campaign trying to soldier on in the face of a national crisis.

In recent weeks, he has come under scrutiny from some members of his own party who feel aspects of his shop are not equipped to counter Trump’s in November. And early fundraising struggles to recent technological difficulties have only compounded some of those fears.

There’s no perfect parallel for Team Biden to consult. But 2008 and 2012—when the country reeled from economic and natural disasters, respectively—offer broad contours of the immense difficulties that campaigning amid American turmoil present.

Four years into the Obama administration, Mitt Romney, the Republican nominee, struggled to break through effectively in the face of a natural disaster. Just one week out from the general election, Hurricane Sandy hit along the Eastern Seaboard, causing mass destruction in two dozen states and some $70.2 billion in damages.“Superstorm Sandy” was categorized just behind Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and hurricanes Harvey and Maria in 2017 in terms of costly effect.

In the midst of the disaster, Romney and Obama stopped campaigning, with the former never fully recovering politically.

“It was like having two teams in a close basketball game and one of those teams being told, with two minutes left to play, to take a seat, while the other team gets to play and run up the score,” Eric Fehrnstrom, a senior adviser on Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign, told The Daily Beast in a lengthy interview.

“We had to cancel events. Our fundraising came to a halt. We had to hit the mute button on our criticisms of President Obama,” he said.

Fehrnstrom recalled having “very intense internal deliberations over whether to put the campaign on hiatus.” (In the briefing call with reporters, Biden said he’s on the phone currently anywhere from four to eight hours a day with advisers assessing the current course of action).

Romney campaign officials also pointed to the unprecedented nature of the crisis’ timing on the outcome. At the final stretch, when strong public relations is particularly important, the storm halted their efforts.

“For me, it was maddening. It was like we took 100 hours and threw them out the window,” Stuart Stevens, Romney's chief campaign strategist, told The Daily Beast. “What Hurricane Sandy did was take away any ability that we had to control the message. We saw the race frozen. It was pretty devastating.”

Stevens said within the campaign, there was one bright spot: Romney’s experience as a governor was uniquely beneficial at assessing the importance of local resources. If he had gone into New Jersey, where the bulk of the storm’s damage hit, not only would it have looked “gimmicky,” Stevens said, but local resources that were critical for on-the-ground recovery would have had to be redirected to his campaign for protection instead.

“It’s just a huge stress-test for the system,” he said about having a nominee appear at a local venue. “It was not something the governor was going to do.”

Now, with the nature of the campaign cycle moving digital to adhere to “social distancing” guidelines, Biden has given no indication of slowing down his campaign or putting a temporary pause on his efforts against Trump.

In September 2008, Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), then the Republican nominee, stopped campaigning as the country’s economic system was on the verge of collapse, citing “historic crisis in our financial system.” He went back to Washington and put out a joint statement with Obama addressing the financial turmoil. But while both McCain and Obama both ultimately voted for an amended version of a proposed $700 billion bailout plan just before the general election, the crisis marked the moment when McCain faded into the background, and Obama became the president-in-waiting.

In today’s political climate, the chances of a Biden-Trump statement are virtually nonexistent.

“Biden will have a harder task than Obama had,” said Jason Furman, who served as the Obama 2008 campaign’s director of economic policy. “It was a little bit easier because Obama wasn’t running against Bush. Certainly Obama criticized lax financial regulation in the Bush administration, but he didn’t make his criticism about Bush specifically.”

Biden will face a more delicate situation, campaign veterans in both parties agreed. On one hand, he’ll have to present a contrast to Trump, a nearly universally reviled figure in Democratic politics, while uniting the country, which includes Republicans who approve of the current administration. According to a new ABC News/Ipsos poll out on Friday morning, 55 percent of respondents polled said they approved of Trump's handling of the coronavirus crisis, while 43 percent disapproved.

“Any criticism from Biden is going to sound like comments from the peanut gallery,” Fehrnstrom said. “Americans will resent the fact that Biden is throwing rocks instead of making a contribution to solving the problem.”

Still, Biden has pledged to be considerably more accessible to the public, and adding daily press briefings to make a case for a different kind of leadership than Trump is a part of that. In his briefing on Friday, he didn’t shy away from hitting the president head-on, saying he’s “all over the map” and “behind the curve.”

“The federal government needs to step up and lead," Biden said. "We need action, not words. We need science, not more fiction. Mr. President, start to tell the truth.”

Reed Galen, a Bush 2004 presidential campaign alum, who now identifies as an Independent and critic of the president, said Trump’s polarizing rhetoric presents an opportunity for Biden, who leans heavily on his ability to connect with voters on-on-one at a time of crisis.

“He has to show that his candidacy and his election represents if not a total turning away of this reality television hellscape that we are living in than a stomping on the pause button,” Galen said.

“Neither Joe Biden nor Donald Trump are epidemiologists. The question is: Who do you trust more with your life?”