Whenever the racist crimes of violent white offenders come to national light, there is always a period when those of us desiring accountability hold our collective breaths and patiently wait — hoping for the best, but prudently expecting the worst. It’s a learned behavior, the self-protective result of knowing that in place of criminal justice, the U.S. has a system that disproportionately criminalizes Black folks and denies them justice.

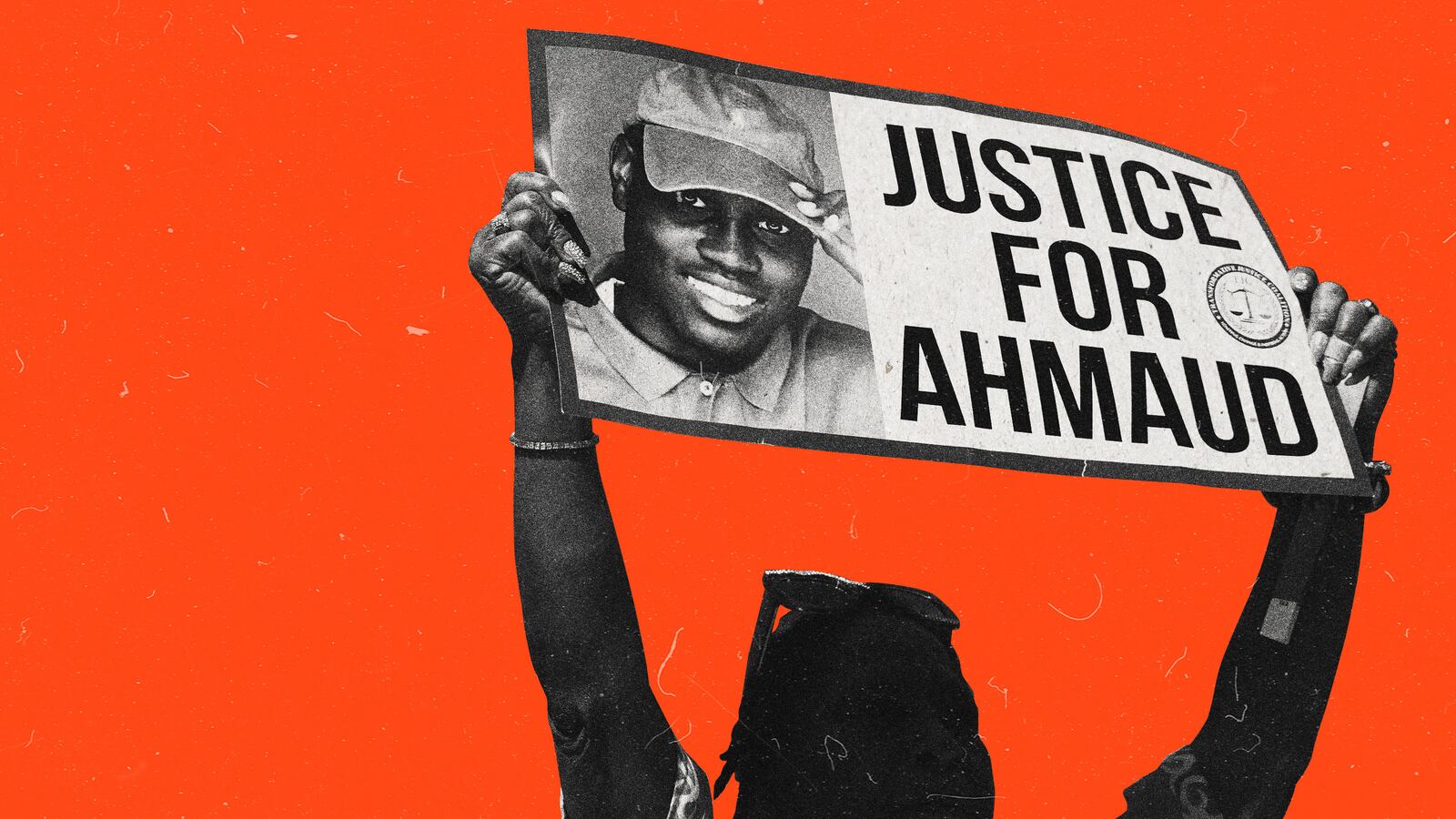

Even when there is unequivocal evidence — as with the video documenting how William Bryan, Travis McMichael and Greg McMichael used pickup trucks and shotguns to track and murder Ahmaud Arbery — there is never the guarantee that an institution built to carry out the whims of white supremacy will break with its original design. The relief expressed by so many on Wednesday, when a Georgia jury announced murder convictions for Arbery’s three white murderers, was itself proof that the verdict was as an exception to the longstanding rule.

Which is why it’s so hard to celebrate this decision, a recognizable anomaly that very nearly didn’t happen. After committing murder on a South Georgia road, Arbery’s three white killers remained free for 74 days, a sign of local officials’ utter indifference to the Black life that had been taken—also manifest in the horrific video footage played at the trial showing Arberry covered in blood and struggling to breathe when police arrived at the scene, and did nothing to help him.

Former District Attorney Jackie Johnson reportedly prohibited area police from arresting Greg McMichael, an ex-cop who worked in her office for 20 years, though footage of Travis McMichael speaking to police who were nothing but kind to him in the aftermath of the murder suggests local law enforcement weren’t much interested in making arrests anyway. The prosecutor who then took over the case, George E. Barnhill, penned a recusal letter that maligned Arbery as a criminal suspect and treated the statements of his killers as if they were the results of an official investigation.

The only reason Arbery’s murderers were taken into custody two months later was because video of the murder recorded by Bryan was given to a local radio host, ostensibly in an effort to demonstrate the killing was justified. But for the public outrage that followed the footage’s leak, the three would almost surely still be living comfortably in their homes. It was only after what was clearly what would have been a “routine” killing of a Black man became a national embarrassment that there was any real chance these killers would be judged for their actions. Even then, they tried to acquit themselves by putting the man they’d killed on trial, and as their lawyers complained about the Black reverends sitting with his family in the courtroom.

A system that only allows for accountability when Black folks’ murders are played in heavy media rotation is, obviously, not interested in the equal dispensation of justice. All too often, even video is not enough; consider the acquittals, mistrials and non-indictments of white defendants responsible for a sickening array of anti-Black violence that has been looped across social media.

Finally, the case of Ahmaud Arbery’s killing is instructive because of what it shows about the inaction normally taken in response to the taking of black life. How many cases are not only never prosecuted, but end with police and local criminal legal system officials cynically and quietly writing off Black death or blaming Black folks for their own killings? How many cases of white violence against black folks never become known to the wider public?

Don’t get me wrong — it would feel far worse if Bryan and the McMichaels were allowed to walk. But in the bigger picture, it sure doesn’t feel much like a win, not just because none of this brings Arbery back, but because so many others who have been cut down by white violence remain unknown.

What we want — the decent among us, at least — is justice, and under this system, that means sending the McMichaels and Bryan to jail. It’s the outcome that, given no other real option, so many of us hoped for. But as Michelle Alexander has written, what we really want is something in place of the nothing we, and here I am specifically talking about Black folks, are accustomed to.

This time, we got something, and an awful lot of people want to pretend that blots out all the nothing we’ve generally received. And yet I know that this system, which in this outlier of a case actually delivered something, doesn’t work. It remains as racist and unequal as ever, and no high-profile exception changes that.

McMichaels and Bryan also knew that, from the moment they grabbed their guns and jumped in their trucks. In the end, what I really want is a system that would never inspire people like them to have the confidence to deputize themselves and assume the cops would sanction murder because of their whiteness.

I want a system that isn’t, almost as a rule, complicit in the killing and abuse and incarceration of Black folks. I want the end of Stand Your Ground and Castle Doctrine laws that let white folks legally justify any horror they can inflict on Black folks based on their wholly unjustified fears of Blackness. And I want white freedom to not be rooted, as it currently is, in the subjugation and policing of Black lives.

That sounds simplistic and idealistic, mostly because it’s hard to see past the edges of what we already know. But that’s what we’re required to strive for in order to get beyond this current system.