Contact: A hundred years before iconic figures like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs permeated our lives, 60 years before Marshall McLuhan proclaimed media to be “the extensions of man,” an Irish-Italian inventor laid the foundation of the communication explosion of the 21st century. Guglielmo Marconi was arguably the first truly global figure in modern communication. Not only was he the first to communicate globally, he was the first to think globally about communication. Marconi may not have been the greatest inventor of his time, but more than anyone else, he brought about a fundamental shift in the way we communicate.

Today’s globally networked media and communication system has its origins in the 19th century, when, for the first time, messages were sent electronically across great distances. The telegraph, the telephone, and radio were the obvious precursors of the Internet, iPods, and mobile phones. What made the link from then to now was the development of wireless communication. Marconi was the first to develop and perfect a practical system for wireless, using the recently-discovered “air waves” that make up the electromagnetic spectrum.

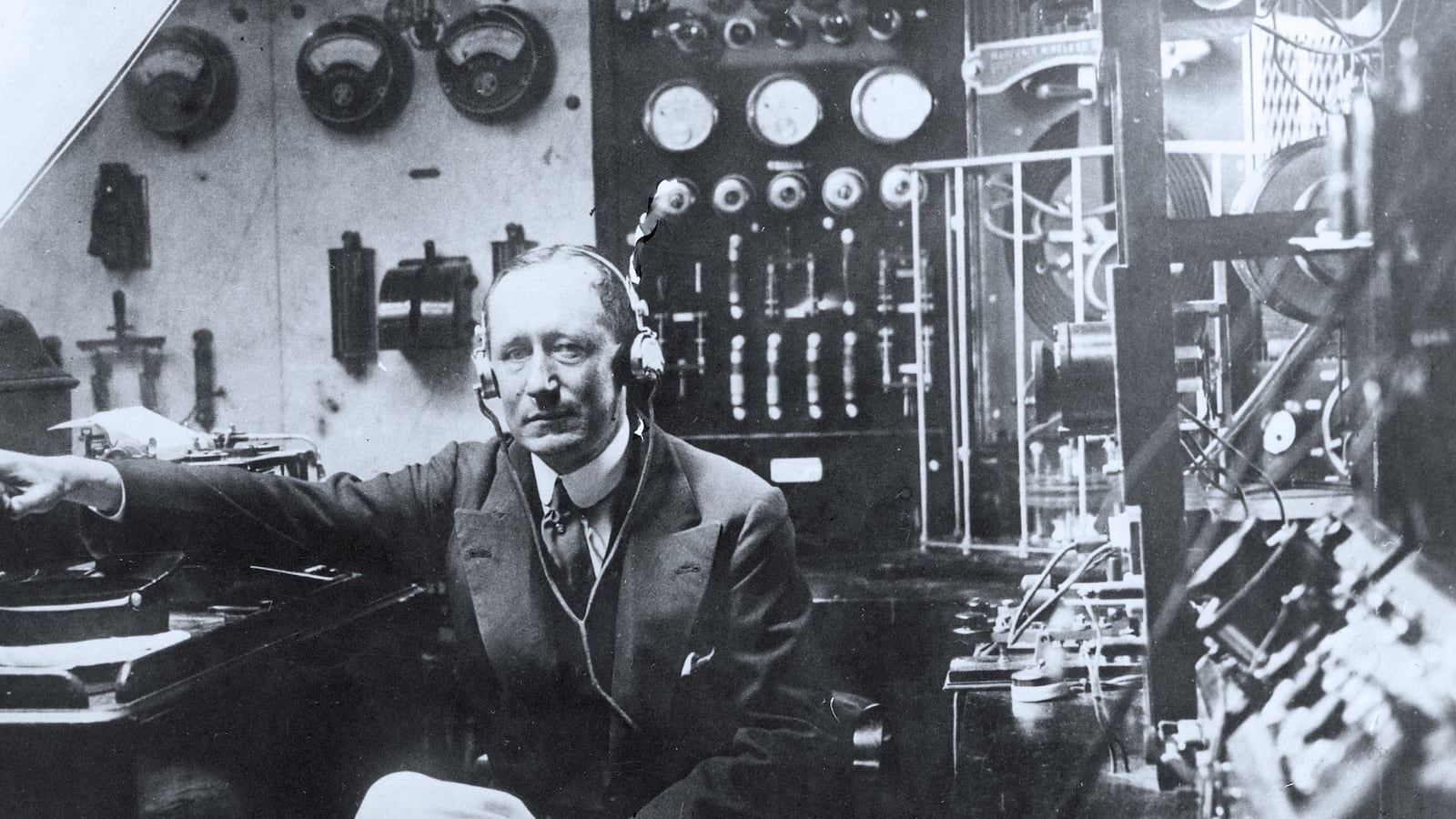

Between 1896, when he applied for his first patent in England at the age of 22, and his death in Italy in 1937, Marconi was at the center of every major innovation in electronic communication. He was also a skilled and sophisticated organizer, an entrepreneurial innovator, who mastered the use of corporate strategy, media relations, government lobbying, international diplomacy, patents, and litigation. Marconi was really interested in only one thing: the extension of mobile, personal, long-distance communication to the ends of the earth (and beyond, if we can believe some reports). Some like to refer to him as a genius, but if there was any genius to Marconi it was this vision.

In 1901 he succeeded in signalling across the Atlantic, from the west coast of England to Newfoundland, despite the claims of science that it could not be done. In 1924 he convinced the British government to girdle the world with a chain of wireless stations using the latest technology that he had devised, shortwave radio. In 1931 he created the world’s first international broadcasting service for his friend, the pope, who didn’t trust Marconi’s other benefactor, Mussolini, to leave the Vatican free to spread unfiltered messages to the faithful. There are some who say Marconi lost his edge when commercial broadcasting came along; he didn’t see that radio could or should be used to frivolous ends. In one of his last public speeches, a radio broadcast to the United States in March 1937, he deplored that broadcasting had become a one-way means of communication and foresaw it moving in another direction, toward communication as a means of exchange. That was prophetic genius.

Marconi’s career was devoted to making wireless communication happen cheaply, efficiently, smoothly, and with an elegance that would appear to be intuitive and uncomplicated to the user—user-friendly, if you will. There is a direct connection from Marconi to today’s social media, search engines, and program streaming that can best be summed up by an admittedly provocative exclamation: the 20th century did not exist. In a sense, Marconi’s vision leapfrogged from his time to our own.

Marconi invented the idea of global communication—or, more prosaically, globally networked, mobile, wireless communication. Initially, this was wireless Morse code telegraphy, an improvement on the telegraph, the principal communication technology of his day. Marconi was the first to develop a practical method for wireless telegraphy using radio waves. He borrowed technical details from many sources, but what set him apart was a self-confident, unflinching vision of the paradigm-shifting power of communication technology, on the one hand, and, on the other, of the steps that needed to be taken to consolidate his own position as a player in that field. Tracing Marconi’s lifeline leads us into the story of modern communication itself. There were other important figures, but Marconi towered over them all in reach, power, and influence, as well as in the grip he had on the popular imagination of his time. Marconi was quite simply the central figure in the emergence of a modern understanding of communication.

In his lifetime, Marconi foresaw the development of television and the fax machine, GPS, radar, and the portable hand-held telephone. Two months before he died, newspapers were reporting that he was working on a “death ray,” and that he had “killed a rat with an intricate device at a distance of three feet.” It seems to have been something like a taser: “I dropped the experiment after that,” he said. “If you have to crawl up to within three feet of something to kill it with elaborate, costly and ungainly apparatus needing the most sensitive adjustment it’s cheaper to use a gun.” By then, anything Marconi said or did was newsworthy, and had been for more than 40 years. Stock prices rose or sank according to his pronouncements. If Marconi said he thought it might rain, there was likely to be a run on umbrellas.

Marconi’s biography is also a story about choices and the motivations behind them. At one level, Marconi could be fiercely autonomous and independent of the constraints and designs of his own social class. He mastered the exercise of power by association, the art of staying above the fray. On another scale, he was a perpetual outsider—the insiders’ favourite outsider, one might say. Wherever he went, he was never “of ” the group; he was always the “other,” considered foreign in Britain, British in Italy, and “not American” in the United States. At the same time, he also suffered tremendously from a need for acceptance that drove, and sometimes tarnished, every one of his relationships.

Marconi placed an indelible stamp on the way we live. Marconi not only “networked the world,” he was himself the consummate networker. Marconi is important because he was the first person to imagine a practical application for the wireless spectrum, and to develop it successfully into a global communication system—in both terms of the word; that is, worldwide and all-encompassing. He was able to do this because of a combination of factors—most important, timing and opportunity—but the single-mindedness and determination with which he carried out his self-imposed mission was fundamentally character-based; millions of Marconi’s contemporaries had the same class, gender, race, and colonial privilege as he, but only a handful did anything with it. Marconi needed to achieve the goal that was set in his mind as an adolescent; by the time he reached adulthood, he understood, intuitively, that in order to have an impact he had to both develop an independent economic base and align himself with political power. Disciplined, uncritical loyalty to political power became his compass for the choices he had to make.

At the same time, Marconi was uncompromisingly independent intellectually. Shortly after Marconi’s death, the nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi—soon to be the developer of the Manhattan Project—wrote that Marconi proved that theory and experimentation were complementary features of progress. “Experience can rarely, unless guided by a theoretical concept, arrive at results of any great significance… on the other hand, an excessive trust in theoretical conviction would have prevented Marconi from persisting in experiments which were destined to bring about a revolution in the technique of radiocommunications.” In other words, Marconi had the advantage of not being burdened by preconceived assumptions.

As Fermi noted, Marconi was not deterred by conventional wisdom. Nor was he deterred by institutional obstacles. In June 1943, the US Supreme Court ruled on a patent infringement suit taken by the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America against the United States government in 1916. The company claimed that the government had infringed a 1904 Marconi patent for radio “tuning.” When the Marconi company sold its U.S. assets, including its patents, to the new Radio Corporation of America in 1919, it reserved this unresolved claim for its own prosecution. It was Marconi’s last commercial interest in the United States. The suit claimed that the U.S. government was using Marconi’s patent without paying royalties. The government argued that the patent was not original and hence invalid. (There is some irony that while the case was still pending, the U.S. Congress voted to erect a monument to Marconi in Washington, recognizing him as the inventor of wireless telegraphy.)

The 1943 Supreme Court ruling, written by Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone stated, “Marconi’s reputation as the man who first achieved successful radio transmission rests on his original patent… which is not here in question. That reputation, however well-deserved, does not entitle him to a patent for every later improvement which he claims in the radio field.” While that ended the Marconi company’s claim against the United States government, it brought a scathing dissent from Justice Felix Frankfurter, the most eloquent voice on the court: “The inescapable fact is that Marconi in his basic patent hit upon something that had eluded the best brains of the time working on the problem of wireless communication… To find in 1943 that what Marconi did really did not promote the progress of science because it had been anticipated is more than a mirage of hindsight. Wireless is so unconscious a part of us… that it is almost impossible to imagine ourselves back into the time when Marconi gave to the world what for us is part of the order of our universe… nobody except Marconi did in fact draw the right inferences that were embodied into a workable boon for mankind.” Frankfurter got the main point: Regardless of the validity of a particular patent in hindsight, it was Marconi who changed the world. In 1943 the United States was at war with Italy, and the U.S. government was in no mood to pay a settlement to a British company over a 40-year-old dispute involving the inventions of a dead “Italian scientist” (as Marconi was called in a lower court ruling). It highlighted the continuing political resonance as well as the mystique associated with Marconi.

The most controversial aspect of Marconi’s life—and the reason why there has been no satisfying biography of Marconi until now—was his uncritical embrace of Benito Mussolini. Marconi was one of the earliest card-carrying members of Mussolini’s Fascist Party, which he saw as a vehicle for establishing an equal place for Italy among the victorious colonial powers after World War One. At first this was not problematic for him. But as the regressive nature of Mussolini’s regime became clear, and as Italy moved closer to Nazi Germany in the mid-’30s, he began to suffer a crisis of conscience, even wondering publicly at one point whether his work had really improved the world or made it a more dangerous place. However, after a lifetime of moving within the circles of power, he was unable to break with authority, and served Mussolini faithfully (as president of Italy’s national research council and royal academy, as well as a member of the Fascist Grand Council) until the day he died—conveniently—in 1937, shortly before he would have had to take a stand in the conflict that engulfed a world that he had, in part, created.

Reprinted from Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World by Marc Raboy with permission from Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2016 by Marc Raboy.

Marc Raboy is professor and Beaverbrook Chair in Ethics, Media and Communications in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University. He is the author or editor of numerous books, and he has been a visiting scholar at Stockholm University, the University of Oxford, New York University, and the London School of Economics and Political Science. He lives in Montreal.