On Jan. 24, 1942, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia surprised Police Headquarters with an unscheduled visit. He was stopping by on a very important matter—he wanted to discuss an imminent danger to his town, an enemy that threatened the economic and moral fabric of the city and that needed to be disabled as soon as possible.

After he left, the order went out. Every available patrolman was to report for duty to aid in the upcoming raid. The target: pinball machines.

Pinball may seem like one of the most innocuous arcade games today. The only action in the game consists of pulling back a plunger to let the metal ball fly and frantically flapping the flappers in a mostly futile attempt to keep the ball in play. Sure, there are some expert players, but, for most of us, it is a game of pure chance.

And that was exactly the problem to mid-century sensibilities. If it was a game of chance, and if players were offered the prospect of an award if they won, even something as small as a free game, then pinball machines were officially a tool for gambling. They were no better than slot machines, the moral crusaders believed. Even worse, with their bright lights, vibrant colors, and fun sounds they were a corrupting influence on the youth.

They had to be stopped.

Throughout the ’40s and early ’50s, one major city after another across the U.S. outlawed the game. Their efforts were effective. If you were a teen in the late 1960s who was eschewing the temptations of LSD and Woodstock and the Summer of Love for a game of pinball, you might run afoul of the law. It wasn’t until 1976 that New York City overturned the ban and made pinball legal again.

The making of a “shakedown racket”

La Guardia had been waging a war to clean up the country for years. As a congressman after World War I, he sponsored a bill proposing a national ban on slot and pinball machines, but it didn’t make it past the House of Representatives. So, it was no surprise that corruption and gambling became a central theme of his campaign for NYC mayor.

The stakes were high, he believed. In a statement issued after receiving his party’s nomination in August 1933, La Guardia said that his campaign was “not merely a political contest but a citizen’s movement for the salvation of the city.”

While he won in 1934, it would take him eight more years before he would finally get anywhere with the ban he had been seeking for over a decade.

La Guardia may have been an extremist in his proposed solution to the problem, but his issue with pinball wasn’t entirely unfounded. There was some evidence that the mob had their sticky tentacles in the game.

In 1948, a lawsuit objecting to the crackdown brought by four pinball manufacturers made its way to the New York Supreme Court. During hearings, the district attorney of Kings County testified that the gang, Murders, Inc., was connected to pinball as they “would assign certain territories to those whom they owed favors, such as stealing an automobile, and that these people would operate a protection racket. It was more or less a shakedown racket.”

In Smalltime, author Russell Shorto explored his own family’s involvement with the mob in a small town in Pennsylvania and discovered their connections with the game. He writes, “The beauty of pinball to the mob was that, since coins you put in didn’t correspond with a quantifiable product like cigarettes or candy, it was impossible to track the machines’ earnings. The high-tech fun of the game plus the possibility of beating it for cash made them addictive.”

Pinball owners, manufacturers, and the shady elements who shook the former down for “protection” were making money, and lots of it. Because these coin-operated games were so hard to win, the house—in this case, the bars, restaurants, hotels, and various other local establishments that acquired a console for themselves—were raking in the losers’ hard-earned dough. It helped that the game was even more solidly set against the players before 1947, when flippers were finally invented.

“Practically every bar and restaurant in the city makes enough from the pin ball machines to pay the rent,” the Johnstown Observer, the Shorto family’s local paper, reported following an investigation in 1954.

In 1942, several days after his visit to the precinct, Mayor La Guardia said, “The pinball machine racket is a direct outgrowth of the slot machine racket, and, as was the case with its evil parent, is dominated by interests heavily tainted with criminality. There is no difference between the two rackets other than the more subtle and furtive methods of robbing the public employed by the pinball machine operators.”

Many of the complaints against pinball mirrored those that had been lobbed against booze several decades earlier during the prohibition campaign.

The breadwinners were frittering away their hard earned cash and stealing from their families; kids were skipping school and using their lunch money to play one game after another; and the game in question was utterly addictive so the only way to stop this behavior was the eliminate them altogether, the anti-pinballers said. La Guardia claimed that pinball brought in somewhere between $20 to $23 million a year.

His campaign finally got the boost it needed following the attack on Pearl Harbor when the U.S. suddenly found itself at war and in need of all the scrap metal it could get its hands on. La Guardia seized the opportunity. “We feel that it is infinitely preferable that the metal in these evil contraptions be manufactured into arms and bullets which can be used to destroy our foreign enemies,” he said.

The New York City authorities had learned a lot about how to go after unsavory elements during prohibition, and they used these lessons to stage a three-week raid that would ultimately net around 3,000 pinball machines, issue over 1,500 summonses, and confiscate nearly $10,000 in coins which were deposited upon the owners’ convictions into the Police Pension Fund (a move, some might argue, that smells a little like a racket itself).

Footage from the time shows warehouses filled with the newly confiscated contraband. Like police department press conferences that display weapons and drug netted from raids today, the NYPD assembled their loot and allowed the media in to produce newsreels that showed the mayor going after his No. 1 enemy with a sledgehammer.

The disassembled machines from that raid would ultimately be turned into four giant bombs for the war effort, and a whole slew of new legs-turned-billy-clubs for the police effort.

LaGuardia may have been the most outspoken opponent of pinball, but he was by no means the only one. Over the next decade, various cities around the country would enact their own bans—Chicago, Portland, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, and Boston among them. Most of these bans lasted for several decades, well into the 1970s.

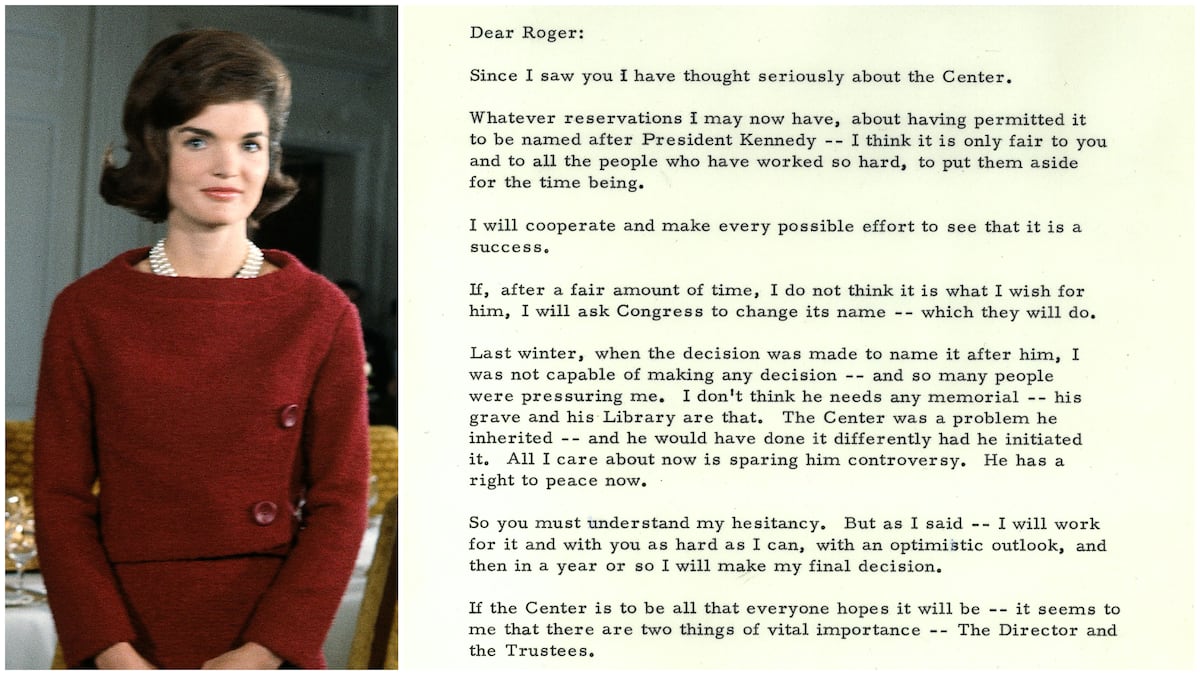

In New York, the ban was finally overturned in 1976 after a master player of the illegal game, Roger Sharpe, demonstrated before the New York City Council that he could easily win against the machine, thus proving that pinball could be considered a game of skill rather than pure gambling.

Today, pinball is legal throughout the country, and the idea that anyone could see anything nefarious in the game is laughable. But it is still under threat, albeit for a completely different reason.

In September of this year, the New York Times reported that the Museum of Pinball in Banning, C.A., was shutting down and auctioning off its 1,700 machines. Visitor traffic was steady, but light leading up to 2020.

“But then came the coronavirus pandemic, and the game, one that the museum’s owner said was already a losing proposition because of the economic climate and the cost of real estate and insurance, was over,” Neil Vigdor wrote. “No flippers could keep the ball in play.”

The owner planned to lease out the museum’s former site to a cannabis farm.