I Am Mother’s parentage is apparent from its initial shots down a long, dark corridor that leads to a chamber where a series of automatic arms begin assembling a one-eyed humanoid robot. From the octagonal curvature of the walls and giant doors, to the fluorescent lighting, muted color palette and ominous atmosphere, director Grant Sputore channels Ridley Scott’s Alien with pitch-perfect devotion. And that’s before he introduces us to the sentient android in question, whose name is Mother (the same as the USCSS Nostromo computer), and whose eventual female charge will, in due time, stalk this steam-filled environment in a grimy white tank top.

Premiering on Netflix on Friday (June 7), Sputore’s feature debut—based on a 2016 Black List script by Michael Lloyd Green—attains much of its power through derivation. Not only is Alien an obvious touchstone for this sci-fi saga, but so too are The Terminator, Ex Machina, 10 Cloverfield Lane and Moon, among numerous other tales about solitary figures trapped in mysterious bunkers or facilities. I Am Mother owns up to this fact, proudly wearing its influences on its sleeve. And though that indebtedness inevitably neuters some of its surprise—including its central “twist”—it also allows the film to tweak expectations, especially those founded on genre conventions, in intriguing ways.

Before it begins tipping its hand, I Am Mother establishes its unnervingly sleek, sterile environs and tone. Having been put together in the aforementioned intro, Mother—voiced with pleasant faux-affection and reasonableness by Rose Byrne, and performed in a physical suit by Luke Hawker—unlocks a collection of human embryos, one of which she places in a spherical pod that’s part of a fancy incubation chamber. This dwelling, wracked by thunderous crashes that cause dust to fall from the ceiling and lights to flicker, is a “repopulation facility” outfitted with a sprawling nursery and child-raising provisions. Like everything else here, this infant-making device is gray and white, shiny and spotless. A countdown begins, and after 24 hours, Mother removes a fully grown fetus.

An ensuing montage depicts Mother rearing this young girl, singing her to sleep with Dumbo’s “Baby Mine,” giving her a stuffed rabbit, reading her The Wizard of Oz, and teaching her ballet and origami. It’s a silky sequence punctuated by the sight of the now-adolescent girl, known only as Daughter, putting cheery stickers on Mother—a sign of their deep, if unconventional, familial connection. When Daughter asks why more children haven’t been hatched, the maternal machine responds, “Mothers need time to learn,” a comment that sounds downright human in the moment, but is laced with ulterior implications that will soon come to the fore.

Cut to 13,867 days later (following an “extinction event” mentioned by opening digital readouts), and Daughter is embodied by Danish newcomer Clara Rugaard as an intelligent, compliant, and all-around ideal teenager. Her days are spent in class with Mother, who gives her exams that seem to focus as much on psychological responses as on traditional school subjects. Theirs is a hermetically sealed co-existence, propped up by Mother’s claims that the Earth is hazardously polluted with contagions. But when Daughter discovers a living mouse in their home, her skepticism is piqued.

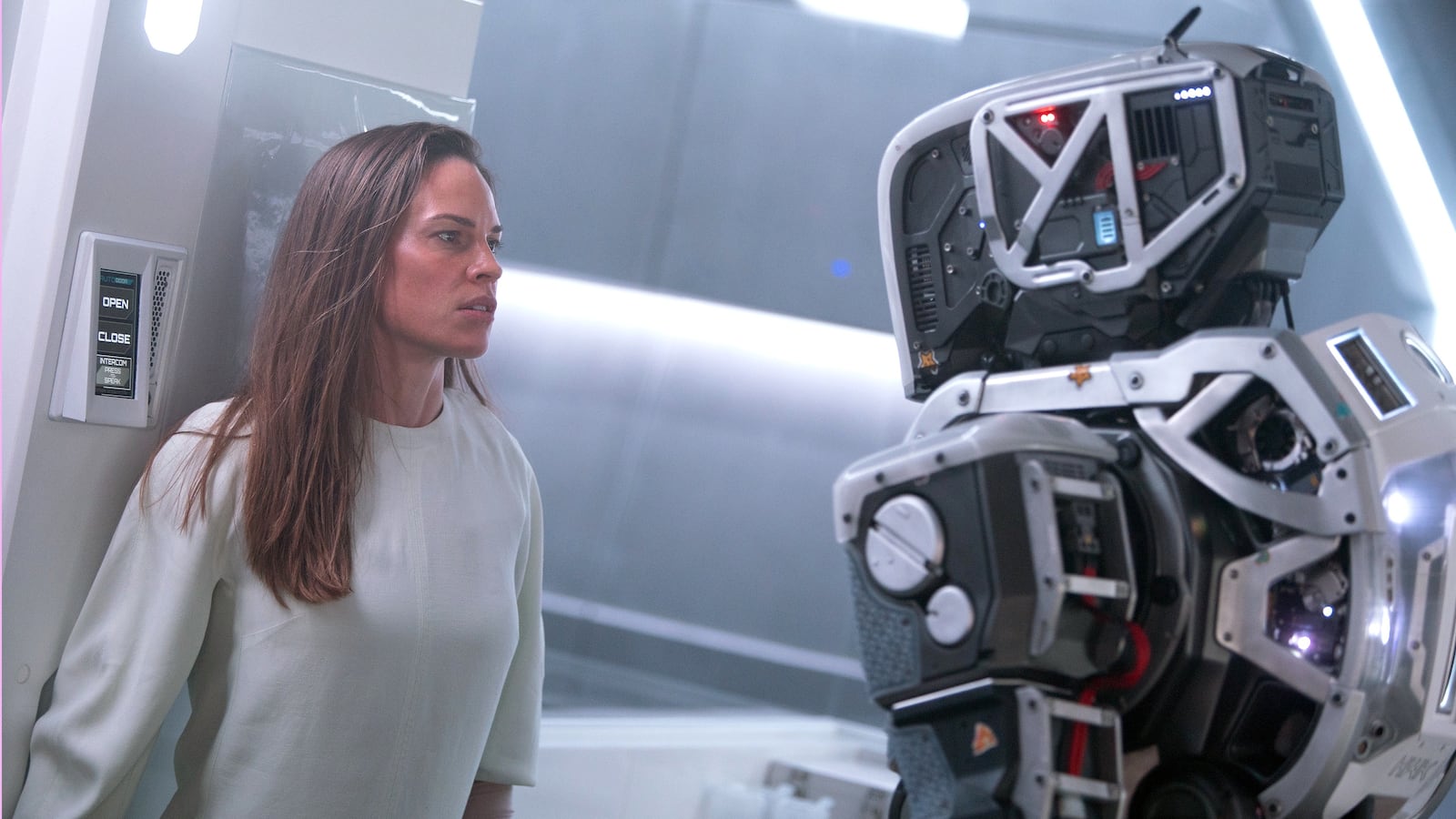

If taking a look-see outside is a faint desire for Daughter, it becomes a far more pressing idea once someone knocks on their door. That mysterious individual turns out to be Woman (Hilary Swank), who boasts a gunshot wound in the gut and pleads for sanctuary from some unknown, urgent threat. Daughter submits and, in doing so, forever shatters the equilibrium of her situation, not only because she’s incapable of hiding Woman from Mother (who she’s right to assume doesn’t approve of this protocol violation), but because what she hears about external circumstances seem to directly contradict Mother’s scorched-Earth story.

Mother’s placid demeanor and Woman’s terrified distrust of the robot are honking-loud warning signs about what’s really going on, and it doesn’t take long before Swank’s harried intruder (when not praying while clutching a homemade crucifix) is trying to persuade Daughter to escape. Given that I Am Mother is such a marvelous creation to simply look at and listen to—Steve Annis’ serpentine cinematography and Dan Luscombe’s luxurious electronic score are precise and portentous—it’s too bad that Green’s script can’t obscure its fated showdown between these rival mother figures. Man’s relationship to machines is also cast in familiar terms, although in that regard, the film is cagier than it first lets on, warping that stock sci-fi dynamic for a fascinating look at the complex nature of motherhood, and the sacrifices it often requires.

After much suspenseful sneaking about and conflict, Daughter does get a chance to experience the wider world, envisioned by Sputore as a hazy wasteland of barren forests, black sand, expansive corn fields manned by enormous farming equipment, and beaches littered with cargo containers. It’s a post-apocalyptic vision that, as with so much of I Am Mother, compensates for its lack of wholesale originality with striking, understated design. Nowhere is that more apparent than with Mother herself, who slightly resembles Chappie and yet has an unnatural comportment and unnerving persona all her own. Key to the character’s menace are Byrne’s line readings, each one marked by hollow positivity that masks something colder and more inhuman lurking beneath.

On the flesh-and-blood side of things, Rugaard capably conveys Daughter’s dawning consciousness, which blossoms at the intersection of coddled adolescence and independent maturity. Swank is afforded less to do in a supporting part that primarily requires her to act agitated and wary. Regardless, the two-time Oscar winner brings welcome gravity to the proceedings, serving as a formidable counterbalance to the mechanical Mother.

Green’s plot is occasionally predicated on too-convenient plot points, be it Mother powering down each night so her kid can wander around as she pleases, or the robot leaving a broken hand out in the open so Daughter can use it to access locked cabinets. No amount of narrative corner-cutting, however, can undermine the aesthetic beauty of this impressive calling-card film, which suggests bigger things to come from its promising director.