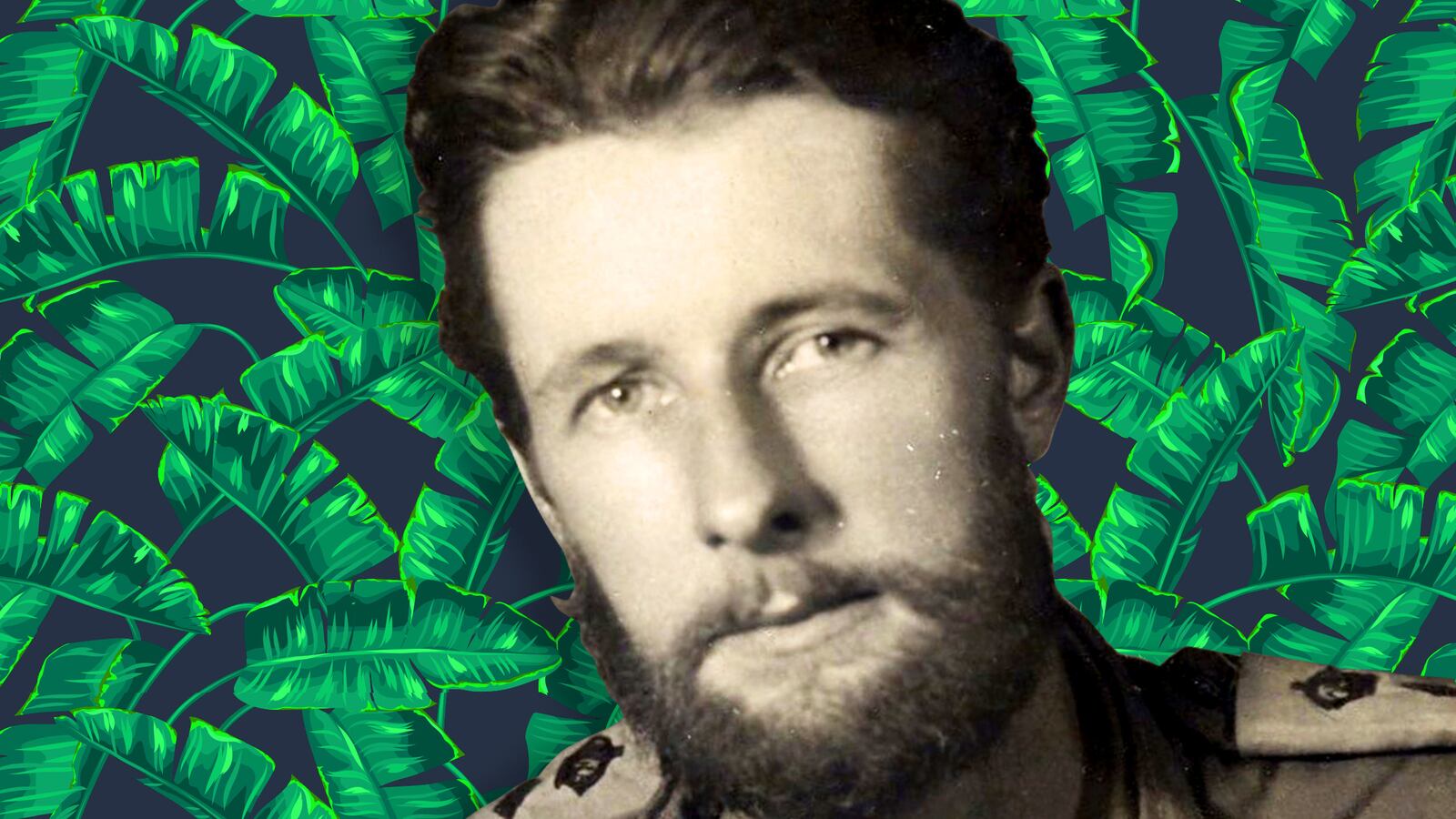

At school when I was 11, I told my teachers Dad was a spy. They didn’t believe me, so I took in the yellowing 1945 Indian newspaper cuttings which described my unorthodox father, Tom Carew, thrillingly, as “Lawrence of Burma” and “The Mad Irishman.” They described dangerous and secret guerrilla missions raising Resistance in Burma behind enemy lines. But of course we didn’t know a fraction of it. He rarely talked about his time during the war, and we his children, at the center of our own universes, rarely asked. As a child, I had a very close relationship with Dad. We were the mischief makers—Dad much worse than I. He was a maverick, rule-breaking, razzle-dazzle dad who was constantly testing and teasing us. But by the time I was old enough to ask more searching questions, Dad’s past was under a different ownership, and there were laws of trespass, for Dad had remarried and my stepmother governed these things.

When my stepmother died in 2003, Dad’s door was swung wide open once again. But, just as we began to reconnect again, the Dad I knew began to slip away with increasingly worrying memory lapses. His first instinct was to outwit them. I found a note in his jacket pocket which read, My name is Tom Carew but I have forgotten yours. I discovered he was showing this note to everyone. As Dad’s past began to ebb away I began the race to retrieve it. The quest—or odyssey as it turned out—was a way to recover not only his story but our family’s, too. I needed to make some sense of it all. It was not just Dad I wanted to stick back together again. It was an exorcism and a ghost hunt. Rebuild him. Rebuild us. Rebuild me.

The new-found freedom to reconnect with Dad meant I could also rummage around in his attic. In the attic were two metal trunks, and in the trunks was another world. Letters, maps, photographs, my grandfather’s pocket diaries starting in 1923; cassette tapes; bound manuscripts; the 1945 Indian newspaper cuttings I hadn’t seen since I was a child. Then, in 2004 an invitation arrived for Dad to attend a weekend-long reunion: The 60th Jedburgh Anniversary. I knew Dad was a “Jed.” And that the Jedburghs were an elite unit of S.O.E (Special Operations Executive), and the first direct collaboration between the American and British intelligence agencies. And that Dad had parachuted at night behind enemy lines to sabotage the Germans in occupied France in World War II in 1944, and then later in Burma where he fought with Burmese guerrillas against the Japanese—where his exploits made him something of a legendary figure. But that was about it.

The Jedburgh reunion was a revelation. From the outside it might have looked an old age pensioner’s do—no outward sign that I was in a room of octogenarian firebrands, mischief-makers, and mavericks. But it didn’t take long. In the first welcome speech they heckled and muttered irreverently, then someone shouted “Forty-eight,” and half the room responded, “Forty-nine,” then everyone bellowed, “SOME SHIT!” and dissolved into laughter. This, I discovered, was the Jedburgh tradition (originating from an American recruit when finishing his fiftieth push-up) reserved for any speaker who dared to go on too long.

Jeds, as they liked to be called, operated in discreet teams of three, consisting of two officers and one radio operator. One hundred teams, three hundred men: British, American, and French. They were a wild, exuberant bunch. Their job was to arm, train, and organize the local partisans into a viable Resistance: ambush convoys; blow up trains, bridges, railway lines, factories, roads, dams, pylons; collect intelligence, code messages; destroy petrol dumps, cut communication lines, do everything and anything to be a thorn in the enemy side. First, to stop German troops getting to Normandy after D-Day; then to slow down their retreat. Each man had passed the strict (and rather bizarre) screening process, and was then trained at the requisitioned stately home and country estate, Milton Hall, near Peterborough. Once deployed, the Jedburghs would be under Eisenhower’s jurisdiction.

The intensive selection process was designed to find out how each man might react in extreme situations in enemy territory and quite quickly I got an idea what the recruiters had been looking for: the unconventional, unsubmissive types—or as the Jeds put it, the troublemakers. For once, high-flyers accustomed to whistling past the finishing line got stuck, while those used to being disciplined for some minor offense or passed over, found themselves going on to the next stage. Dad told me that in 1939 he’d come in at the bottom of his class of officer cadets, with more punishments built up by half term than they had punishing parades to attend. “I didn’t cause any trouble,” he tried to explain, “I just questioned everything. When I was given an order to polish boots, I asked why? ‘TO SEE IF YOU CAN DO IT!’” Dad roared, mimicking the officer, then began to laugh, “So I polished one. Oh, they could get a lot of distaste into the word, ‘CAREW!’” I discovered he didn’t change much during his Jedburgh training. One weekly report read, “Is not a fool, but gives a good impression of one.”

That reunion weekend was the first time Dad and I had spent on our own for years, and it was from this point that I began my research in earnest. Astonishing how quickly, once you begin to rub the lamp a little, propitious coincidences begin to occur. The release of classified files at The National Archives inundated me with code-names, reports, letters, and telegrams on thin oniony paper stamped Top Secret in red. In Dad’s first mission report I learned he was parachuted into the forested uplands of eastern France and spent his first night with the Maquis (French partisans) in the chateau at Granges Maillot where he “suffered excessive hospitality” and I can guess what he meant by that. I googled Granges Maillot, and that summer made a pilgrimage with my husband, Jonathan. Near the chateau, a tiny sign pointed the way to a memorial to the French Resistance fighters who had died here. Up a track, across a field, into a wood … and deep in the wood, weeding the memorial, was the grandson of the woman and owner of the chateau who had given shelter to Dad and his fellow Jeds all those years ago. It was astonishing to me that anyone would still know where the original Drop Zone was located, yet half an hour later, with our new French friend as our guide through the forest, we stood silently in a large clearing: the very spot where Dad landed in the middle of the night, at 24 years old.

Dad cut his teeth in France, but it was in Burma, a few months later, that he made a real name for himself. Burma was far more dangerous and complicated. First, he was twice the size of both the local inhabitants and the enemy (with footprints twice as big!), so no chance of blending in. The other complication was that once the Japanese had been got rid of, the same Burmese who would be Dad’s guerrillas would be setting their sights on the next job in hand: removing their colonial masters, the British. As an independent 25 year old with Irish roots, Dad was in total sympathy and found himself embroiled in a very awkward political situation. He laughed darkly when he told me that he was almost court martialed at the same time he was awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order—one of the highest medals for bravery).

The more I learned, the more Dad’s anecdotes began to attach themselves to history for the first time. The time when he was hiding in a French schoolteacher’s house and the BBC sent a coded message to him which he heard on the radio; the time he hid in the rafters of a Burmese hut as the Japanese combed through a village looking for him; the time he was picked up off a river in the jungle by a flying boat, like James Bond. I unearthed sound archives of interviews, 1945 film footage of him walking out of the jungle in sarong with a dagger on his hip, a Burmese bestseller in which he had an extraordinary walk-on part, a Christmas card from the head of the CIA, a letter in which he reveals his friendship with Patricia Highsmith. It was an exciting time, but full of pathos, too, when Dad’s dementia progressed to the point where I could not share my finds with him.

It was my husband’s idea to take Dad to see The Lion King, for the razzamatazz and to take his mind off his memory lapses. The three of us walked up the red-carpet steps in the theater foyer when Dad, one step from the top, tripped on something. And fell, and started rolling down the steps. The usherettes froze, the doormen froze, the other theatregoers froze, we all froze. And stared. As an 85-year-old man rolled over and over, bump, bump, bump, all the way down to the bottom. And then sat straight up. Unscathed, unbruised, and perfectly fine. There was a loud sigh of relief from the usherettes. What we had just witnessed was Dad going straight into a parachute roll—arms tucked in and totally relaxed. His Jedburgh training was still second nature to him—it just clicked in. He stood up, dusted down his trousers, enjoying every second of our incredulity.

There is an impulse to bear witness. I knew I had a far bigger story in my lap and I wanted to tell all of it. Not just the guerrilla warfare and secret stuff, but what it was like living in Dadland with all its contrails. The good and bad, happy and sad, the successes and disasters, and all the jaw-droppingly-mad episodes in between. My discoveries, with more twists and turns and surprises than I could ever have bargained for, followed a trajectory that paralleled the restoration of our own father-daughter relationship. My father’s life was a 90-year journey through the 20th century into secret and shady corners of history in war and peace. The war he handled spectacularly, the peace was far more challenging for him, but it was never dull. I had a front-row seat for quite a bit of it. Which is why I describe bringing all the threads together like plaiting the limbs of a wild octopus. It has also been a way of preserving that precious window of liberty we enjoyed in those last years before his death: when Dad and I were able to rediscover our closeness, the joshing, and that shared mischievousness that had never gone away.

Keggie Carew is the author of Dadland. She has lived in London, West Cork, Barcelona, Texas, and New Zealand. Before she began writing, her career was in contemporary art. She has studied English literature at Goldsmiths University of London, run an alternative art space called JAGO, and opened a pop-up shop in London called theworldthewayiwantit. She lives near Salisbury, in the UK.