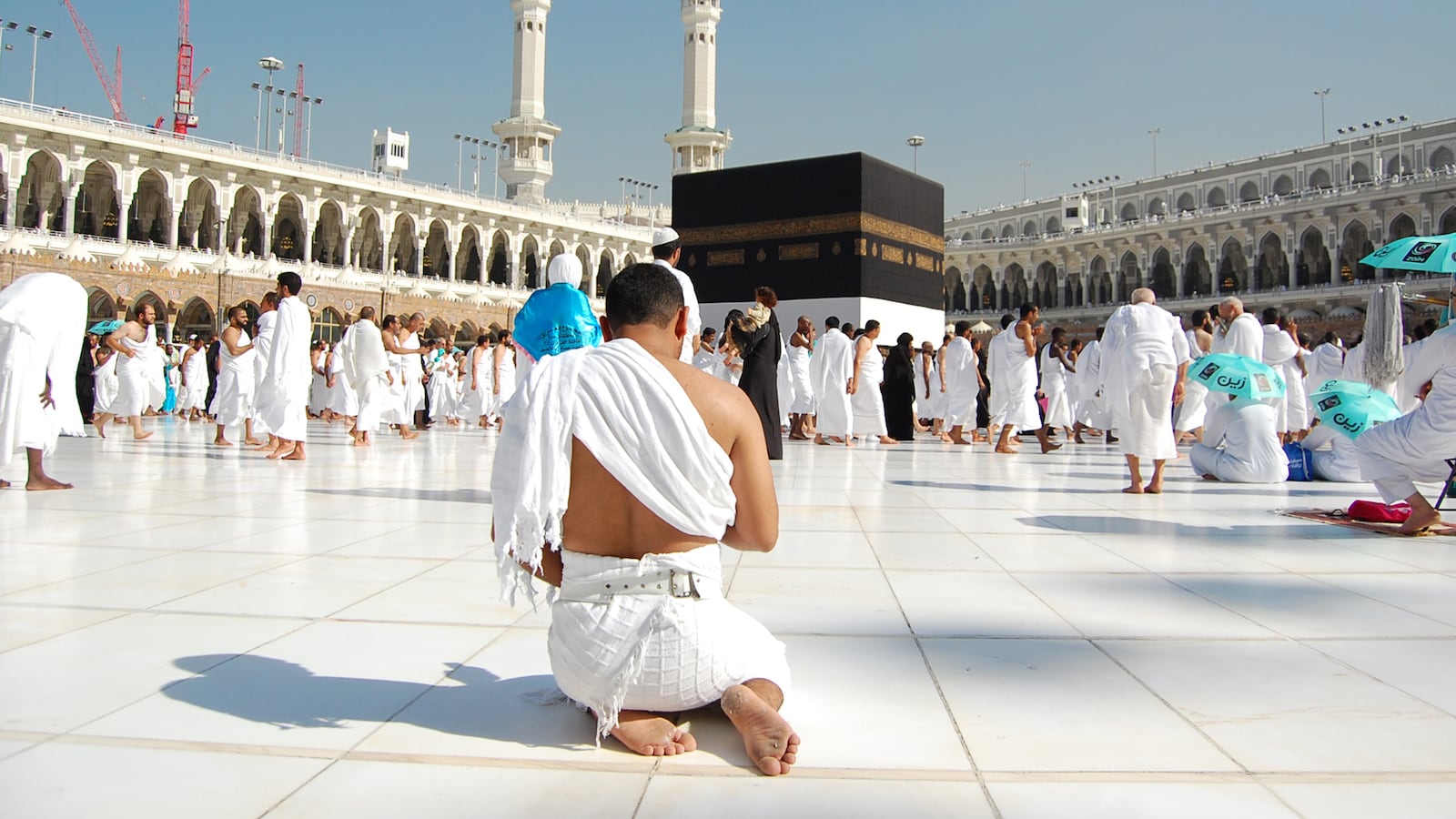

We were in the middle of Islam’s boot camp—the roughly five to nine days of Hajj, the heavily ritualized pilgrimage every able and requirement-fulfilling Muslim is told to perform, and it all takes place at Islam’s ground zero in Mecca and a few suburbs around it. In Mecca sits the black cube called the Kaaba toward which 1.7 billion Muslims are commanded to face when they pray, five times a day. It is not possible to ascertain what percentage of this incredibly diverse mass of humanity are overcome with enough piety to do as told. After being there, I realized in a sense that it was Islam’s mosh-pit.

It was full-on Hajj. We walked from Muzdalifah to Mina, the world’s largest tent city. Here there are “more than 100,000 air-conditioned tents” sprawling across twenty square kilometers. Historically, pilgrims brought their own tents. In the ’90s, fires raged through sections of the city, so the tents that met my eyes were fiberglass coated with Teflon.

I felt awful. We hadn’t showered in three days and had walked for miles in the dust. We walked bowlegged to avoid further chafing of our inner thighs. Our white ihrams had lost their made-in-China gleam. I had stopped eating and drinking sufficiently because I was terrified at the thought of having to use another overused Saudi Hajj style toilet, the most disgusting I have ever seen in the world. A seasoned traveler, I had traveled to more than 30 countries and I came from India, a country that practically invented “disgusting toilets,” enshrined for cinematic history in the opening sequence of Slumdog Millionaire.

Our feet were calloused from our Hajj-mandated open-toed sandals. If it was good enough for the Prophet, it was supposed to be good enough for us. Mina was divided into camps representing every country. “Welcome Russian Pilgrims,” said one. “Caribbean Hajj,” said another. I noticed flags from every corner of the world, from Fiji to the Maldives, and yet there were three glaring omissions: no Stars and Stripes, no Union Jack, and no Star of David. My majority-American group marched under the innocuous maple leaf of a less-controversial neighbor.

The inescapable call to Zuhr prayers resounded. In order to pray, I would need to perform the wudu, (ritual, pre-prayer cleansing) but that would involve a visit to the dreaded Saudi toilets. Imagine a port-a-potty with no seat—just a hole in the ground. In that enclosure, pilgrims are meant to defecate, piss, and then shower. No toilet paper, no flush. When showering, you are standing in a puddle of brownish water. Is it simply dirt and sand from the previous occupant, or something worse? Dirty water from adjacent stalls is flung over your head, and you can only hope that your neighbors are as clean as you imagine yourself to be. These are some of the most unsanitary conditions in the “civilized world” the Saudis claim to be part of. Threats of pandemics hang over the Hajj every year. The soundtrack of the Hajj experience is a cacophony of sneezing, coughing, and retching. Many pilgrims and Saudi guards wear surgical masks.

With some shame, I opted sacrilegiously to skip the wudu. I pretended I had already done it by going for a short walk. I may have broken the letter of Islamic law by shirking the cleansing ritual, but in my mind I was all the cleaner for it.

Shahinaz texted me how she had sneaked an early-morning fag, post-Fajr, in one of those “Satanic shower shit piss bin Laden inventions.” At one point during Hajj, I stopped eating just so I would not need to use the bathrooms for anything but urination. Both she and I knew that the bin Laden family, one of the largest construction conglomerates, had been charged to modernize (aka destroy Islamic history) Mecca and Medina. Osama bin Laden, one of the sons, was for a while in charge of this in Mecca. He like the 15 (of 19) hijackers of 9/11 had definitely performed Hajj. Perhaps more than once and perhaps these toilets were a bin Laden novelty of modernization. This family was the closest to the despicable, ruling Al-Saud monarchy. They always got all the contracts.

While taking a smoke break outside my tent, I was approached by Abdullah Jaffar, the British doctor in my group, with a stern face.

“Brother Parvez,” he said. “Do you understand the global network of smoking?”

“Yes,” I said. “There are smokers everywhere.”

His voice lowered, “Let me show you how it works.”

He drew a map of the globe in the air with his fingers, illustrating his conspiracy. “Here is America. And here is Britain. And here is Brazil. They all manufacture tobacco. Do you know where it ends up?” He jerked his hand across his map toward the Middle East and South Asia.

“See? Where the majority of Muslims live?”

I let the kook rant.

The doctor traced a path between these countries, indicated a conspiratorial flow of tobacco from non-Muslim nations to the heart of Islam.

“See?” He smiled, as though his irrefutable logic had fallen gracefully into place. “It’s a conspiracy by the Jews of America.”

I tried not to roll my eyes.

“They want the Muslims to die of lung cancer.” His voice rose. “It’s all connected! Be careful, brother. Not just for your health, but also for Islam!”

I hastily extinguished my cigarette.

The reason I didn’t argue with him was because I had always known this. Islamic supremacy = White supremacy. Both, as just one example, are anti-Semitic.

The filthy alleys between the tents of Mina stretch for miles. The tents themselves are identical, and the only way to distinguish one from the other is to check the flag and group names. I lost my way easily before spotting someone from my group.

Back in the tent I dared to pray in the Sunni way in front of all my Shia group members. At this point I had lost my desire and fear to blend in, and my stubborn defiance was on full display. People stared and whispered to one another. I tuned them out and focused on the higher purpose that had brought us here in the first place.

As had happened many times now, women seemed to have disappeared suddenly and without warning. They must have had their own segregated tents apart from their husbands or male “guardians.” I wondered if these women knew about the furor-ridden debates raging in the kingdom regarding women’s rights, segregation, and equality.

While in Mina, I had seen a tweet from Al-Waleed bin Talal, one of the self-proclaimed reform-minded princes, arguing that women should be allowed to drive in order to abolish illegal work by undocumented immigrants. He claimed that this would lead to 500,000 fewer foreign chauffeurs. Critics, as they always did, screamed with outrage at this tweet. Sheikhs often appeared on Saudi television decrying the female driver: “If women started driving, what would they do if their car breaks down? They will be raped!” This and similar mindsets continue to prevent Saudi Arabia from entering the 21st century.

That night I went for a walk, because I was feeling claustrophobic. The men around me were taking up more than their fair share of space. I felt like I couldn’t breathe. But the streets didn’t bring much comfort. Excrement, trash, sirens wailing, and countless more pilgrims sleeping on the streets. These were another class of pilgrims—those who had come into the kingdom undocumented during the Hajj season. They had come looking for work. Many of them had found work, but many hadn’t. So they whiled away their days, often begging. Many beggars had missing limbs; I assumed they’d been caught stealing. The landscape looked like the day after a bloody battle, with countless bodies, many broken, squirming, and stretching across the landscape. There was a parallel Hajj going on. I ran into one of my Hajj leaders, by now a regular smoking buddy.

I complained to him about my tent mates.

“My mother used to tell me that all good people should take up the space of a coffin. You know, not encroaching on the personal space of the people around you,” I said.

“Unfortunately, not everyone carries that morality,” he replied.

“And what about these streets? Do they even realize that people like us sleep in air-conditioned tents? This is not the Hajj of equality that the Prophet envisioned.”

“You’re right,” he said. “I’ve been bringing groups here for 15 years. So much has changed even within that time. These people don’t even have visas. I can’t even tell you the things I’ve seen.”

“What will happen to them when the Hajj season ends?”

“They will either find illegal jobs, end up in Saudi prisons to be deported or get their limbs chopped for some crime or another and then beg.”

Stomping out his cigarette, he looked into the distance. “I’m so glad they don’t allow non-Muslims. The West shouldn’t be allowed to see this side of us.”

Satan’s day had arrived with the next morning. On this day, we were meant to confront Satan in a symbolic recreation of Ibrahim’s (Abraham) confrontation with the devil. When Ibrahim left Mina, Satan appeared to him three times. Each time, the angel Jibreel (Gabriel) showed up and told Ibrahim to pelt the devil with stones, which made him disappear. Three pillars at a place now called Jamrat mark these three moments in which Ibrahim successfully confronted the devil. According to some traditions, the three pillars stand at the exact spots where Ibrahim threw stones at Satan and thus are representative of the temptations he needed to overcome to get God’s blessings.

Our group leader corralled us into groups of about 20. I was assigned to lead my group and given a tiny Canadian flag to wave. We began to chant alongside tens of thousands of other Muslims,

Labbaik

Allah humma labbaik:

O my Lord, here I am at Your service, here I am.

You have no partner.

Here I am.

Praise be unto you

Yours alone is all praise and all bounty

And Yours is the sovereignty.

You have no partners.

We entered a series of tunnels, miles long, that shot through the many hills of Mecca. It never stopped—the shrieking noise of the chants that reverberated through this chaotic claustrophobia. Shahinaz was not with me. She had feigned illness to avoid the barbarity. This was just one example of an entirely Saudi-created Hell.

“Can’t do it much longer,” Shainaz texted pleadingly from her tent-trap in Mina. I acknowledged her and felt guilty. Thankfully her judgmental women companions would be gone all day.

“Take a Xanax and just sleep for a few hours,” I advised.

“Perfect,” she said.

For about three hours we trudged through the tunnels and the enormous roar. There were moments when savage behavior was common in the mini-stampedes that happened between tunnels. There were bodies sprawled on the rocks, mostly from dehydration or other medical problems. They tried to avoid the avalanche and fervor of the determined stoners.

“I need water. I will die,” said a woman carrying a baby.

She clearly lived in a Western country. I had bought many hydration packets of the kind used by sporty types, most of which I had given away. This was the last and I gave it to her, urging her to use it with thrift.

“Shouldn’t they have clean water for us?” she said. I nodded, helping her up. She was soon lost. My long walk to Satan was of a devilish dehydration I had never experienced. We passed kiosks selling all manner of Islamic tchotchkes. But NOT ONE sold water. Was this a deliberate Saudi Satanic creation?

But then! Ahead a truck threw boxes of water bottles into a riot-like situation. I was going to be a savage like them. I grabbed two and hid them in my backpack. And I decided I could no longer share if I wanted to end this long walk from hell alive. Many in my group started yelling for water. It was nowhere to be found after that truck, which I believe was from God.

A group of clearly poorer pilgrims were wailing around a corpse. “He was my uncle,” a young man cried.

“He was pushed down and he had no water. It was too much for him,” explained a youth, “but we lost everyone and his wife.”

“It’s a blessing to die in the holy city,” said a loudmouth, showing no compassion.

I searched for a security guard and showed him the body. After an eternity, cops came to the scene and hauled the deceased pilgrim away. The nephew was not allowed to go with them. This dead man would forever be forgotten in one of the Saudi unmarked corpse holes.

This was an ideal environment for stampedes, which occurred with reliable frequency every couple of years. In 2015, over 2,000 pilgrims were trampled to death here. If this particular part of the Hajj experience is intended to feel like a march to Hell, the Saudis have succeeded in constructing the perfect environment. The general vibe of the place evoked in my mind the heavy-metal song “Smoke on the Water” by Deep Purple. The grinding, malevolent guitar riff had always brought to mind the presence of evil.

In the mid ’90s, I had the opportunity to see Deep Purple play at the Nehru stadium in Delhi. By this time the band was several generations out of style in the West, but clearly not in the Third World. Clearly the only chance of recreating the fame of their heyday tours lay in a country like mine. I fought hard to secure tickets. The massive stadium was sold out. A concert-goer, imagining himself in his fantastical version of America, where he wished he lived, a college youth gushed to a newspaper, “These dudes are gods, man!”

Smoke on the water, fire in the sky … Was this it? I banished the lyrics and hurriedly replacing them with the chant. I had recently become addicted to a new series called Game of Thrones on HBO. This was the kind of stuff the armies of the Lannisters or the Starks would recognize.

When we arrived at the pillars, I readied my pebbles. As I threw my first stone, I remembered when one of my short-lived Hajj buds, Hossein, had joked about how his Tehran pals (and yes, if a poll was conducted, the vast majority of Iranians will be found to not be religious fanatics) laughed during stoned jam sessions sometimes about the pillars representing America, Israel, and England for the detested Basij (religious police) style pilgrims!

The noise now was too deafening for me to make out anything that was being said other than, “Allahu Akbar.” It was an unearthly roar. As pilgrims rushed past me in all directions, flinging their stones, I saw a manic look in their eyes, as though it were the end of days. I and many others were pelted by carelessly thrown pebbles, along with slippers, bedrolls, and other “cursed” or “unlucky” personal totems and objects that were poorly aimed at the pillars.

There didn’t seem to be anything godly about this horrifying place. I noticed that women were being pushed to the ground around me. Their “sisters” (PC, Muslim-speak) tried to hold them up. When I offered my hand to help pull a woman up, it was slapped away by another woman. Even here in Hell, gender segregation was self-enforced.

In the mad rush, I myself was pushed down by a phalanx of marching Indonesian pilgrims who inadvertently rammed me to the ground and walked over me ceaselessly and, more important, inhumanely. Was this the part where I die? I was rescued by a kind Nigerian beggar. She had no hands, but offered what little arm she had left. For me, her simple act of kindness, though it flouted the rules of Islamic gender segregation, would have had the Prophet’s approval. As far as I could tell, only this butchered, humble beggar obeyed Muhammad’s deepest calls for compassion.

I had survived a stampede. I could have died, if not for her presumably getting a one-way ticket to heaven, or perhaps hell, in my case. I didn’t have any riyal to give her. She didn’t ask.

I staggered out of Hell and out into the sun. Although I had been tasked with keeping my group together, I had lost all of them. There was no way we could have stuck together in that mayhem. So I headed to our planned meeting place: Gate 17. When I arrived, I was immediately scolded when a fellow pilgrim caught a whiff of my deodorant. I had dared to break structure, because I could not bear to smell myself. In truth, Islam’s canon also tells us Muhammad loved perfume.

“Are you wearing perfume?” he said with a judgmental whisper, just loud enough for the whole group to hear.

I ignored this guy’s comment. Haters gonna hate.

I tried to find some strength and solace by thinking of the spiritual simplicity of my ancestors, and the lengths and hardship they went to perform their Hajj, sans any of the “modern” conveniences that I now enjoyed.

I emerged from Jamrat exhausted, bruised, calloused, dehydrated, and spiritually broken. I wasn’t sure I could go on.

The experience of the Hajj had stripped away everything about me that made me a modern civilized man. Two nights ago, I had sat next to a Pakistani guy who was here to repent the “honor-killing” of his sister-in-law he had participated in. I felt newly in touch with whatever primal force that lay dormant in me—the caveman brain that thirsted for blood. It is at this point in the Hajj that pilgrims are commanded to sacrifice a goat, just as Ibrahim had done after sparing Isaac.

Reprinted from A Sinner in Mecca: A Gay Muslim’s Hajj of Defiance by Parvez Sharma. Copyright © 2017 by Parvez Sharma. Excerpt used with permission by BenBella Books. All rights reserved.