Around 9 a.m. Tuesday at the voting site I worked in Brooklyn, a disagreement broke out between poll workers. Outside, it was a rather blustery fall morning with high winds. Inside the high school gym we were using as a location (go Tigers!), we burrowed deep into our coats and scarves. A rafter window was left open overnight; a custodian was on his way to climb up and close it.

Shutting the window won the popular vote among us poll workers shivering as we directed voters to their ballot booths, peddling the promise of democracy. Every vote counts, we believed. That was why we had signed up to run the polls.

But then there was "Florida." Every election, Florida screws something up, acts as a contrarian, so that’s what I decided to call the woman who, despite our democratic process, stopped us from closing the window. “Florida” had allergies and needed adequate airflow, so we left it open. (For a few hours, at least—by evening time the window had been shut.)

My Election Day began at 5 a.m. I walked the few blocks from my apartment to the polling place in darkness. I joined an army of fellow poll workers, many of them twenty-somethings like me, an army of metallic puffer coats and skinny jeans.

We had heard that the coronavirus created a shortage of poll workers, traditionally retired or elderly people. So we signed up en masse. There were U.S. history teachers, costume designers, and dental assistants making up my little squad in Brooklyn.

“My coworkers had today off, so a lot of them went hiking,” the history teacher told me. Anything to distract from the news. “But I wanted to do something.” So she spent her long Tuesday at the polls, knowing Wednesday she would have to get up at 6:30 a.m. and face a bunch of high schoolers after the most freakish election of our lives.

The first person I saw who showed up to vote just after we opened at 6 a.m. wore a floppy bucket hat and the affected smile of someone whose parents pay their rent in a rapidly gentrifying New York neighborhood. The last person I saw who slipped through our doors right around 8:57 p.m.—minutes before closing—was a FedEx delivery driver with bags the size of Wisconsin underneath his eyes. I thanked him for being an essential worker. In a quiet, tired voice, he returned the appreciation.

An editor at this website once told me that you cannot write a news story without talking to people. Much of the story of this election has focused on certain people—the two men duking it out, their staff, the power players. As a poll worker, I saw the story of the election through the voters who actually make it all happen.

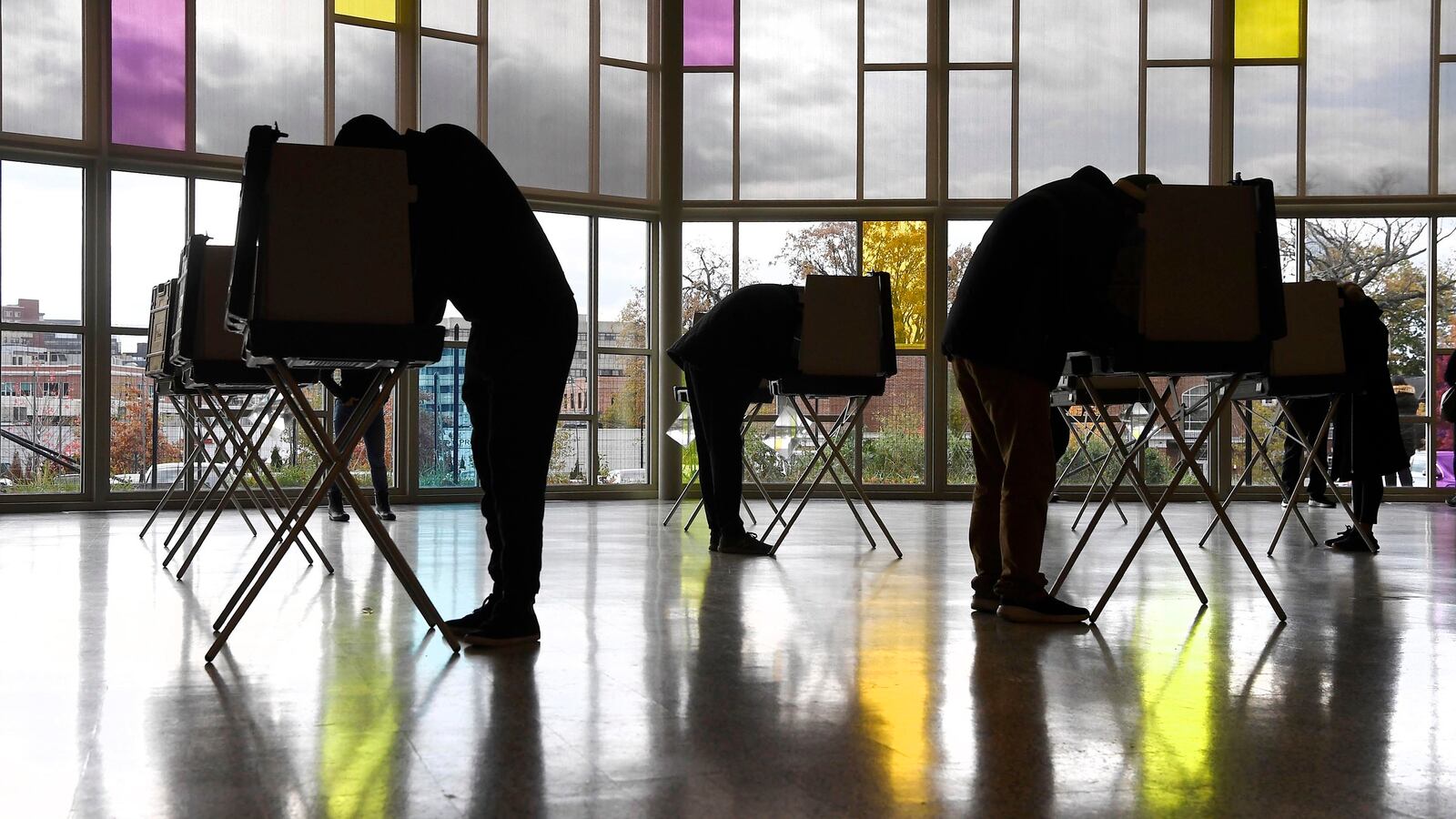

I saw so many eyes peeking above face masks that looked exhausted, but determined. They moved slowly and deliberately around the poll site, stood in the booths for minutes on end, making sure their ballots were correct.

“I really want to get this right,” one young man, a first-time voter, told me. He was unfamiliar with his local candidates, so he did not vote for any. He only filled out the presidential election. He came to me asking if it was acceptable to leave some spaces empty. “I filled out the important stuff, right?” he asked.

This man was not quite sure how to vote, but he knew he needed to. He was navigating a system that continually confuses and disenfranchises people. But he still took time out of his day to get on a bus, or a train, or his own two feet to try and fix it.

I was assigned to help voters put their ballots in the counting machine; a position I dubbed Scanner Girl in my mind. Setting up the scanner was a meticulous job, dripping with the formalities of a bureaucracy. Every compartment of the machine had to be opened and checked, every task initiated inside a booklet. My arms overflowed with paperwork.

One veteran of the polls, an avuncular gentleman from BedStuy, noticed my complete ineptitude. He told me it was his tenth election, gently ushered me aside, and within minutes completed all 34 steps it takes to set up a ballot scanner. Then he promptly sat in a folding chair by the corner and fell asleep.

Over a million New Yorkers voted early during the week leading up to Election Day. Only around 500 showed up to the polling place I worked on Tuesday. It was not the turnout my location’s coordinator, a young woman with a no-nonsense attitude and workman’s flannel shirt to match, hoped for. We were not slammed with the kind of lines you may have seen on social media posts in your own battleground state. But people did come.

People came with babies on their hips or in strollers. People came in sweatpants; some came in full suits. People came with questions, their inquisitiveness a welcome relief from a season filled with pundits who speak like they know everything. People came for the first time, and people came for the sticker. So many people came for the sticker.

People brought food for us, dragging in boxes of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee. Our toilets were located in the middle of an old girls’ locker room, which was dark and spooky and illuminated only by flickering lights. Mentally, I was there. Physically, I was there a lot, too, because my caffeine intake rendered hourly bathroom breaks.

By the time the polls closed, the Dunkin’ coffee was long gone, and I was almost deliriously tired. I kept yawning behind my face mask. I wanted Election Day to end immediately. I wanted to go home, down a glass of wine, lie on my couch, and fall asleep to the sweet sounds of John King’s CNN screen tapping. But we were not finished yet. We had to print our results, report them to the Board of Elections, pack up the space, and break down the tables. It was tedious, and it was worth it.

On Wednesday, states continue to count ballots. Election Day has morphed from 24 hours to a potentially weeks-long process. On social media, people are horny for results and guessing what might happen. If you ask Trump, it’s been called already—no need to keep up those pesky tallies.

After serving the voters of Brooklyn for just one day—a sliver of a responsibility when it comes to what volunteers are doing in states like Nevada and Pennsylvania—I know I can be patient. Every single voter deserves to be counted.

As I got into the ease of my job, directing people to the scanner machine and making sure they knew how to use it, I got used to hearing the satisfying thump that means a ballot has been properly processed. With that, I would chirp out a “thank you” and send voters off. I loved the thump.

But often the thump did not come too easily. Frequently, actually, an error message would pop up—someone did not fill in an oval all the way, someone accidentally voted for Biden twice, on both the Democratic and Working Families party lines. Ballots are confusing (some might argue this is intentional) and mistakes happen.

I would tell the voter what they did was wrong and direct them to go back and try again. Legally, they have three shots. Often, it only took one screw up for someone to do it right the next time. A few needed three attempts. Either way, they all got it done. Not a single person who came through the door was going to miss their chance to vote. So, yes I was exhausted by the end—and also incredibly fulfilled and proud.