My 11-year old daughter points at the scar on the inside of my left wrist and asks, “How did you fall on the glass again?”

“When I was a teenager, I tripped on the edge of the carpet and fell through a glass door. Boom! My wrist was cut, and doctors had to stitch it up.”

“Did it hurt?” she asks for the thousandth time.

“A little,” I tell her.

My daughter kisses the scar. I kiss her freckled nose.

“Your brother is waiting. Go play,” I say.

I came up with that story long before I had children, and retold it until now to protect my family’s reputation and the image of me the world has come to know. I had not been able to bring myself to tell the truth about the prominent scar on my left wrist.

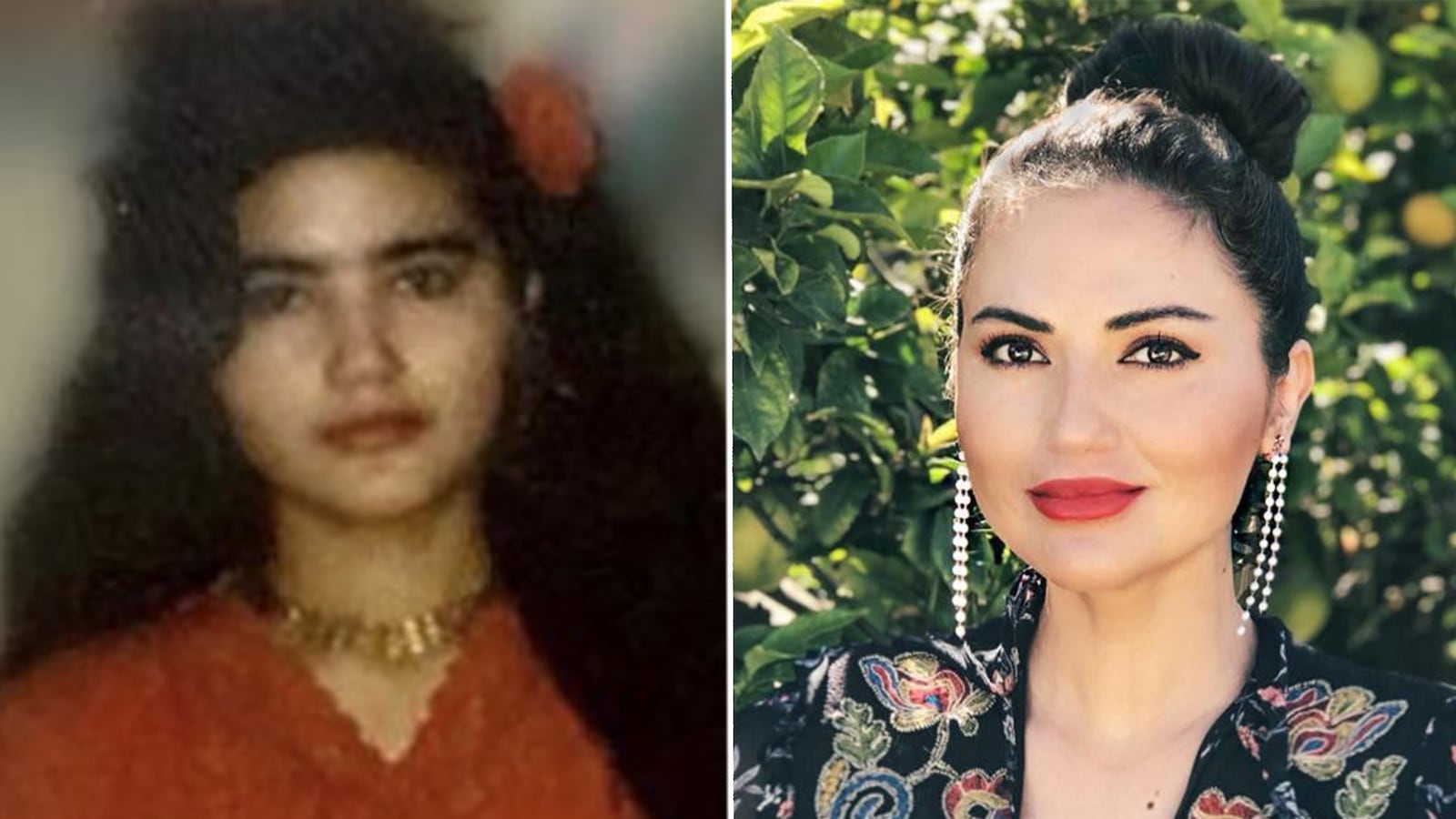

In the winter of 1994, a distant relative from Canada visited my family in Afghanistan. During his stay, he took photos of us with his fancy Japanese camera.

I washed my face and decorated my hair with a big red bow that matched my shirt. I licked my fingers and ran them over my thick brows. My body was starting to become curvy. I enjoyed my photos, my face still childlike at 13.

A few months later, a marriage proposal came. It was unexpected. My mother’s cousin, who’d seen the photo, wrote to her, praising his sons, especially the younger one. He had just finished college and had a job as an engineer. He was in his mid-twenties and ready to start a family.

“Your daughter is a beautiful young woman. She looks much older than 13 or 14. I would be honored if she was to become my daughter-in-law soon,” he wrote. “My son’s wish is to marry (a) traditional and good Afghan girl.”

This written proposal was followed by a few phone calls, asking for my hand in an arranged marriage between his son and me.

For weeks my parents were whispering about his proposal: “If only she was a few years older.” My mother would continue, saying something like, “but there’s nothing left to hope for here with the Taliban in power. At least she can go to Canada and make something of herself, get an education,” her voice shaky.

And so, the few phone calls turned into a distant engagement.

“She’s just a child,” my father would say.

“But imagine her life in Canada versus here, in this hell. She can’t even go to school to finish high school, let alone a college education,” my mother would respond. “We may even have to marry her off to a Taliban soldier; then what?”

In return for the marriage, my parents were promised that I could go back to school in Canada, where the Taliban’s disapproval of educating girls had no sway.

My fiancé refused to come to Afghanistan for a marriage ceremony. He told me he was concerned about the unpredictability of life under the Taliban. And so we packed our bags and left Afghanistan on a charter flight to Pakistan. A few months later, my prospective husband arrived with his mother.

He was tall and slim, fair with dark brown hair covering his broad forehead. I thought he was a good-looking man.

On my wedding night, I was excited to be the center of attention in my puffy white dress and painted face. I was also terribly frightened. I badly wanted to play and to dance with the other girls who attended my wedding with their families.

The toughest part came a few hours later, when I was left alone with him in a hotel room he’d rented for the night. My female relatives had told me to be a good wife, and to allow my husband to get close to me. I didn’t really understand it until that haunting October night of 1995.

A few days after the wedding, I was given a new passport with a new birth date. I was not 14 anymore; I became 19 overnight. Child brides weren’t a novelty in Afghanistan, and I’d seen many girls prior to me marrying at 14 or even 13 and 12, but years later and in Canada I realized that international laws and Canadian law prohibited any sexual relationship between an adult and a child.

My new husband stayed with me in Pakistan for another week before leaving for Canada to start my paperwork to join him there. A year later, on Christmas Eve of 1996, he greeted me in Toronto’s International Airport. After he handed me a bouquet of red carnation flowers, he came close and whispered in my ear, “You have turned quite fat. I’m so disappointed and turned off.”

I began my new life in a two-story townhouse we shared with his entire family. The day after my arrival, I was assigned my chores: clean, cook and do the laundry. And my married life began.

My husband often complained that I was stubborn and childlike. Maybe he too believed that I was five years older than my biological age.

He said that I wasn’t obedient, and because of that I wasn’t a good wife.

“A good woman, a good wife would make the rice fluffy and the lamb stew tender, waiting to please her husband upon his arrival,” he told me. “If I wanted to marry a woman with ambition, then I would find a wife from here, not a child from back home.”

And I believed.

But my love for education exceeded my ambitions to be a good wife. I reminded him of his promise to my parents. And I was finally allowed to attend school, but I often had to miss it to complete my house chores.

It wasn’t long before my health was waning, and my depression became obvious to anyone who met me. I wasn’t who I had dreamt of being: a college student, a woman who had hopes. Instead, I was in a black dark spot, wishing for my life to end.

A half-uncle and his wife who lived close by often told me to be patient and to obey my husband.

“You don’t want your parents to worry about you. You don’t want to bring shame upon the tribe, and if you leave him that’s what you will be doing,” they said.

And I believed.

I was utterly lonely, hopeless, angry, and depressed. Living life became a chore.

The scar on my wrist is not from tripping over a glass door. It’s from my suicide attempt. I started thinking of suicide shortly after I went to Canada. Prior to that attempt, I often walked to the middle of a bridge near our home and stood there, looking at a busy freeway below, full of speeding cars. I stood on that bridge and thought about jumping. I remembered my parents, eagerly awaiting my monthly phone call. I thought of my young siblings; I thought of the bitter memory it would leave my family if I jumped off the bridge. I even thought about the unlucky driver who would see my body smashing into their windshield.

Cutting my wrist wasn’t planned. It happened on impulse on one of those days that living didn’t seem like an option anymore.

A few hours later when I woke up at the hospital with my wrist stitched and in bandages, I cried. Getting pushed to the edge of death was the silver lining for me to want to live again.

Soon after, life took a different turn when I met a neighbor who was also an Afghan woman.

“You can’t continue to waste away. Fight for your freedom! Go and get educated, help other girls in your shoes,” she said.

She reminded me of my dreams and love for education. Finally, she bought me a gift: an airplane ticket back home.

“This may be your only chance to be happy again,” she said.

Since the official fall of the Taliban, Afghan women have made so much progress since then. The culture of child brides still exists in Afghanistan, but parents are not forced into marrying off their children in hopes of sending them to school and giving them freedom like my parents did. They sent me away as a child bride hoping I would thrive and be free.

When I returned to my family, now in Pakistan, they saw a scrawny, aged young woman. I was 20 and, at an age when many girls start to toy with the idea of a first serious relationship. I was granted my Islamic divorce.

Thus, I felt it with every particle of my body when I heard then-first lady Laura Bush say that “only the terrorists and the Taliban forbid education to women.”

I know what it’s like to not have any freedom. I know what it’s like to fear wearing nail polish to save my fingers from being cut by the Taliban.

My life has changed since then. My parents warned me that life would be difficult as a divorced woman, and I returned to Canada.

“Go back and reclaim your dreams,” they said.

A couple of years later, I met a progressive and wonderful Afghan man who is now my husband, remarried, and over time moved to the Bay Area, started a family and resumed my education.

Nowadays, I’m a woman who fights for other women’s rights. A woman who loves to learn. A woman who has prominent laugh lines on her face. Yet, I lost years of my childhood. I did not attend school from 7th to 11th grade. It’s hard for me to remember the kid I was before my marriage at 14. Trauma devours everything that came before. Only fragments remain.

Thus, in the past few months as the US began peace talks with the Taliban, I have been restless.

The mere thought of an expansion of Taliban control and possible return to past oppression, and the slaughtering and stoning of women has been triggering painful flashbacks.

Most people don’t know about my life. But I’m telling it now because I owe it to all the other child brides who don’t have a voice and to all the women who have suffered similar agonies.

As the U.S. has begun peace talks with the Taliban and with Afghanistan’s presidential elections, originally scheduled for April but now postponed until September, looming, the Afghan people and specially Afghan women are feeling restless, uncertain, and fearful as they wait to see if the Taliban will reclaim enough power to once again regulate and govern our lives and our freedom.

The mere thought of returning to past oppression, to the slaughtering and stoning of women, has been causing Afghan women PTSD-like symptoms and flashbacks.

The peace that Afghans yearn for can’t come at women’s expense. Women have been demanding a place at the negotiating table after being sidelined, and we want peace alongside our rights and equality. We want the great powers of the world to speak up for us and demand a settlement that explicitly supports the rights of women, and commits all parties to protecting Afghan women against human rights abuses.

In two years, my daughter, still a child, will be the age I was when I became a bride. I am telling my story to the world now because the girls her age in Afghanistan deserve our attention more than ever. Their education, their childhood, their livelihood cannot be jeopardized. All those girls deserve to have a childhood free from the fear of losing their freedom. They must be free to be children—and not be forced into the world and treated as adults while still just children.