Last week in Las Vegas, mayors nationwide told Uncle Sam to let Americans go green.

If only it were that easy.

The 180 elected officials attending the annual meeting of the U.S. conference of mayors in Sin City unanimously adopted a resolution urging the federal government to let states and localities make their own marijuana policy. The bipartisan sponsors—including, along with the usual suspects, leaders like Jean Robb, the Tea Party–backed conservative mayor of Deerfield Beach, Florida—seemed to show that the war on the war on drugs is now in full sway, a process that has accelerated since voters in Colorado and Washington state embraced weed legalization at the polls last fall.

The mayors, who claim to know a thing or two about tight budgets and wasted public-safety dollars, don’t want the feds to impose new enforcement burdens on already-strapped police forces and are also keeping an eye on the potential revenue from taxing the always in-demand substance.

So they’re stepping into the void left by a Department of Justice that has essentially been silent on the legalization measures. Attorney General Eric Holder promised a response “relatively soon” way back in February, but has gone mum since then. Perhaps encouraged by that silence, politicians have become increasingly vocal in trashing the war on drugs like never before, a line of criticism that taps into growing liberal and libertarian distrust of the Obama administration’s expansion of the surveillance state and drone warfare.

Considering the messy realities of regulation, the local leaders are offering to take the lead from the federal government, effectively letting cities and states emerge as legalization laboratories.

“It’s akin to the spirit in the country today relative to gays and lesbians and same-sex marriage and so forth,” says William Euille, the first African-American mayor of Alexandria, Virginia, and a co-sponsor of the resolution. “People have come to realize that we need to stop punishing people who want to live their lives a little bit differently.”

The mayors stress that they are joined not in advocating any particular approach to marijuana—be it decriminalization, medicinal programs, or full legalization—but simply in calling on Washington to let local communities decide the matter for themselves. And while gay-rights advocates might bristle at the comparison (which Bill Maher makes regularly on his HBO show Real Time) of their fight for equality before the law with the push for legal pot, Euille is right about one thing: public opinion has moved sharply in favor of both causes over the past few years. Even some longtime foes who maintain that marijuana is a “gateway drug” and that its association with criminality is inextricable concede that they are swimming against the tide, and that it is only a matter of time before some form of legalized pot is a reality of urban life in America.

“The horse is out of the barn,” William J. Bratton, the former police commissioner for New York City, Los Angeles, and Boston, told The Daily Beast in an interview. Though Bratton sees the trend toward legalization as “unfortunate,” he says it’s really just a question of the details at this point, and in particular what the regulatory infrastructure will look like. On that front, he expects police chiefs, regardless of any resolutions their bosses have signed, to be frustrated by the new order.

“It's phenomenal in a country that is so fanatical about ensuring purity of prescription drugs that the regulations governing marijuana are clearly laughable for their lack of effectiveness,” he says, referring to the medical-marijuana laws that have created a certain amount of chaos in Los Angeles, the city council there voting at one point to ban dispensaries entirely before voters moved to restore them at the ballot box, scaring lawmakers into repealing the ban.

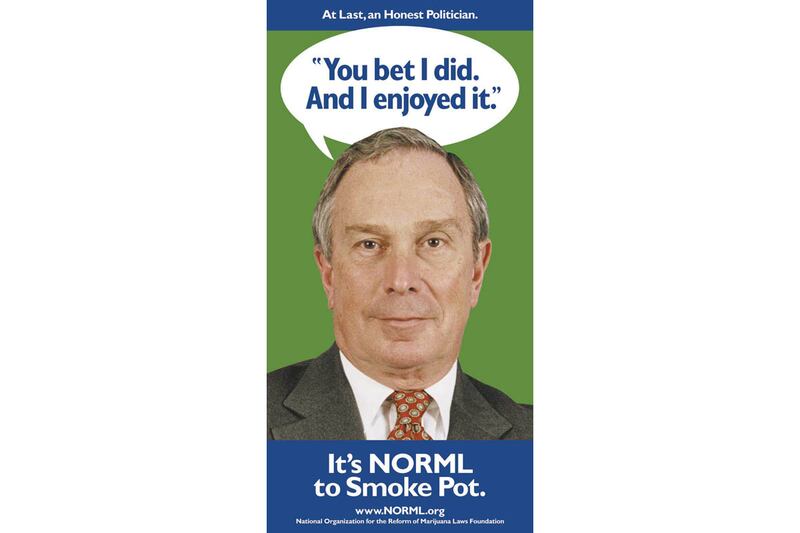

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has dismissed medical marijuana as a “hoax” and been criticized for the pot-related arrests, overwhelmingly of young black and Hispanic men, resulting from his controversial “stop and frisk” program, perhaps appropriately did not attend the conference. “You live with it,” Bratton said of the prospect of an independent inspector general overseeing the NYPD, which he said was inevitable given the electorate’s outrage about the racial impact of marijuana arrests. “Is crime going to basically all of a sudden go out of control? I don’t think so.”

But the mayors who sponsored the resolution said they did so out of frustration with the slow pace of the federal debate on drug policy, and a belief that the long arms of D.C. shouldn’t constrain their respective cities on social questions like this one. As for what the new regulatory environment might look like, Mark Kleiman, UCLA professor and Washington state’s “pot czar,” says he likes the idea of experimenting with different drug laws but has doubts about local politicians possessing the knowledge or resources to set up an effective regulatory scheme.

“I don't think that total deference to local control is going to work well because of the race-to-the-bottom problem,” he says, expressing fear that one or two states or cities with weak regulations might take over the market in the same way that Delaware has become ground zero for the credit-card industry. In a worst-case scenario, the profit motive means any nascent marijuana industry would encourage excessive use and even target children, much as Big Tobacco did before such tactics were banned in the 1990s.

Which is to say that all sorts of sticky details still need to be worked out. But in the meantime, these mayors are trying to advance the conversation.

“I happen to have a relative who has glaucoma and has used marijuana to great relief,” says Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman. “The reality is that we as mayors work with the people,” she said, while members of Congress in Washington “don't really know the heartbeat of what’s going on every single day.”