KHARTOUM—Their hands were up but the soldiers beat them anyway. Again and again, the soldiers would raise their whips, holding them high for a moment as if to taunt civilians venturing toward the site where sit-in demonstrations have become the focus of resistance against oppression. And then the whips came crashing down. The demonstrators retreated to a roadway and began to shout, “Peaceful protest! Peaceful protest!”

It did not matter. The soldiers advanced again, weaving through cars and seeking out victims. Demonstrators stampeded through the streets. For those young men on the edge of danger—close enough to see the whites in the soldiers’ eyes, but far enough from their whips—it became a kind of game: run away from the soldiers and shout back at them something brave when both sides paused. There was a surreal soundtrack of boots slamming against pavement and then laughter.

“The people will always win,” a high-school student told me as we huddled behind a block of cement. He said his name was complicated, so I should just call him “B.” He had curly hair and wire-rimmed glasses. “They will use their guns soon,” B said. It was time to leave.

We walked toward the center of the sit-ins in front of Sudan's army headquarters. Just over a month ago, millions of people gathered here to rock former dictator Omar al-Bashir out of power. When a military junta removed Bashir, it promised to hand over authority to civilians. But since then the military have hesitated, and all the while some soldiers have tried to rattle the demonstrators. It’s not known on whose orders.

The future now balances between authoritarianism and something more democratic. On Wednesday morning, civilian and military officials said they were close to reaching a deal about Sudan’s transition. But on Monday troops paraded throughout the city in a circus of brutality, and events have shown that whatever semblance of peace exists in Sudan, someone will try to sabotage it.

Different units—from the military, a paramilitary group called the Rapid Security Forces, and the intelligence services—all seem to be marching to their own tune.

"B" and I walked down Khartoum’s dirt streets as the light failed. Temperatures finally dropped below 100 degrees, so it counted as a cool night for Khartoum.

We paused around the Khartoum Central Bank, near a square filled with new demonstrators. Gun-toting soldiers stood only a few meters away from hundreds of protestors.

The lights went out. I lost B.

These soldiers were older, bigger, tougher, with barrel chests. They retreated under a tree—it seemed this was not their fight.

“This is going to be the longest night, like Game of Thrones,” said a man in a blue shirt. Before I could get his name, we heard the sound of gunshots nearby. It was not clear from where or from whom. We retreated into the sit-in zone.

Everyone was telling everyone to calm down while they themselves were panicking, as if by wishing calm upon someone else it could rub off on them. That was when the first wounded person was hauled past Mr. Blue Shirt and me. I followed the casualty into a makeshift medical clinic.

Sudan’s revolution is a mass of confusion, but successful revolutions are never just about the tumbling of a wall or the election of a leader, they are about changing an entire system. That takes years, decades, generations and may never really be complete.

In Sudan, the protestors overthrew a dictator, but they know they aren’t finished. In fact, the way the organizers of Sudan’s demonstrations put it, they haven’t accomplished anything yet. The goal of the Sudanese Professionals Association, a collective of trade groups organizing protests, is to remove the system Bashir presided over.

The inside of the medical clinic smelled of heat and blood and pain there in the dark. The government had just shut off the power minutes before I arrived. One doctor pulled out his phone to give him light.

It was around 10 p.m. and another doctor told me they had five gunshot victims so far. The doctor wore a gas mask pulled up on the top of his head.

I walked outside the clinic with him, and a troupe of soldiers with red berets were walking calmly through the protest site. Why were they there? Nobody was sure.

Doctor Gas Mask told me protestors had discovered an intelligence officer was wearing an army uniform in the protest site. In essence, a spy. He was turned over to the army.

There have been clashes between the military and intelligence agencies throughout Sudan’s uprising, and the animosity apparently continued that night.

A crackle of gunshots rang out from nearby. Doctor Gas Mask and another medic in a white lab coat turned to look at each other, and silently raced back to the clinic to prepare for injuries.

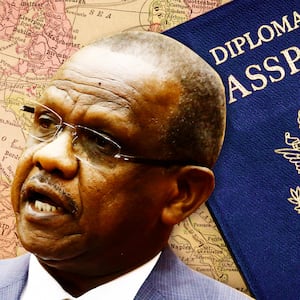

Lt. Gen. Mohamed “Hemeti” Hamdan, head of the Rapid Security Forces paramilitary unit, is now one of the most powerful men in Sudan. He is notionally second in command in Sudan’s current hierarchy, but Hemeti tells western diplomats that it was his idea to overthrow Bashir.

Hemeti’s influence comes from the minerals he profits from in Darfur and support from the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, according to western officials. Hemeti also supplies troops for the Saudi-UAE adventure in Yemen, these officials and relatives of soldiers say.

After throwing Bashir out of his palace, the junta moved in. When I visited recently it seemed a world apart from the dust-swept streets in the rest of the Sudanese capital. Inside the palace’s buildings, magnificent chandeliers hung from high arched ceilings. The hallways were long, wide and lonely, making visitors feel like children who sneaked into a haunted house.

As Doctor Gas Mask ran to the sit-in’s medical clinic, I walked to part of the protest zone that has a giant stage. There, thousands of Sudanese turn on their phones’ flashlights at night to create a constellation of light, and this night they began to chant: “Freedom, peace and justice!”

This was the first night since Bashir’s downfall that there was violence in Khartoum, and it seemed hope for a peaceful transition to civilian rule was slipping away. As the protestors chanted, a chorus of bullets came from the opposite end of the site. The shooting would continue in spurts for the rest of the night.

What makes Sudan different than some other revolutions across the Middle East is the demonstrators nearly religious belief in nonviolent methods. The protestors just keep eating violence—for days, weeks, months.

I hiked up to the top of a hill, closer to the gunfire to see what was going on. In the area below me, there were clusters of people being treated for gunshot wounds. Waves of the wounded were carried away from the gunfire and into the street below me. I saw Doctor Gas Mask tending to people, running from one to another, the tubes on the mask flailing about.

Western diplomats, who were surprised by the strength of protests in Sudan, have tried to pressure the military junta to give up power. Their message to the junta is that if it does not give up power to civilians the kind of international support Sudan needs will not come, one diplomat told me. On the other hand, a civilian-led transition promises to receive a host of benefits from the West, including massive debt relief.

Some Western nations say they would not recognize a military government if it keeps control of the country, but others have a more ambiguous position. And then there are the Americans. U.S. diplomats are trying to coordinate international action, but the White House seems out of the loop here in Sudan, according to U.S. officials speaking privately. An interview request I sent for official comment was not returned.

Around midnight I walked back to the Central Bank. The barrel-chested Sudanese soldiers who had retreated in the face of protestors were still there, watching the scenes of revolution while loafing under a tree. It was unclear which unit they were from, but it was a testimony to how easy it was for troops to avoid confrontation with protestors who embrace non-violence.

Four people died in the protests Monday night and 200 were injured—77 of them from bullet wounds—according to the Sudan Doctors Committee.

I spotted Amgad Fareid Eltayeb, a spokesman for the Sudanese Professionals Association, the group orchestrating protests. He is someone whose phone rings every 10 seconds and is always rushing off to another meeting. Amgad must have meetings in his sleep. I asked him what was going on. We both laughed, because neither of us really knew.

That day, despite the violence the military and civilians reportedly had had productive talks and agreed on the structures and powers of a transitional government.

“I don’t know,” Amgad said. “Everything was going fine.”