In a rare interview, the novelist Cormac McCarthy once made a strong claim about the power of the novel. The form, he said, can, “encompass all the various disciplines and interests of humanity.” While McCarthy and Jane Austen are not exactly kindred spirits, Austen wrote something similar in a famous passage in Northanger Abbey. Mocking those who disparage novels as frivolous and consider only non-fiction serious, she wrote, “It is only a novel… or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humor, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.” McCarthy and Austen would likely disagree on which books realize the form’s potential, but both see the novel as intellectually supreme, a sovereign domain of the highest achievement.

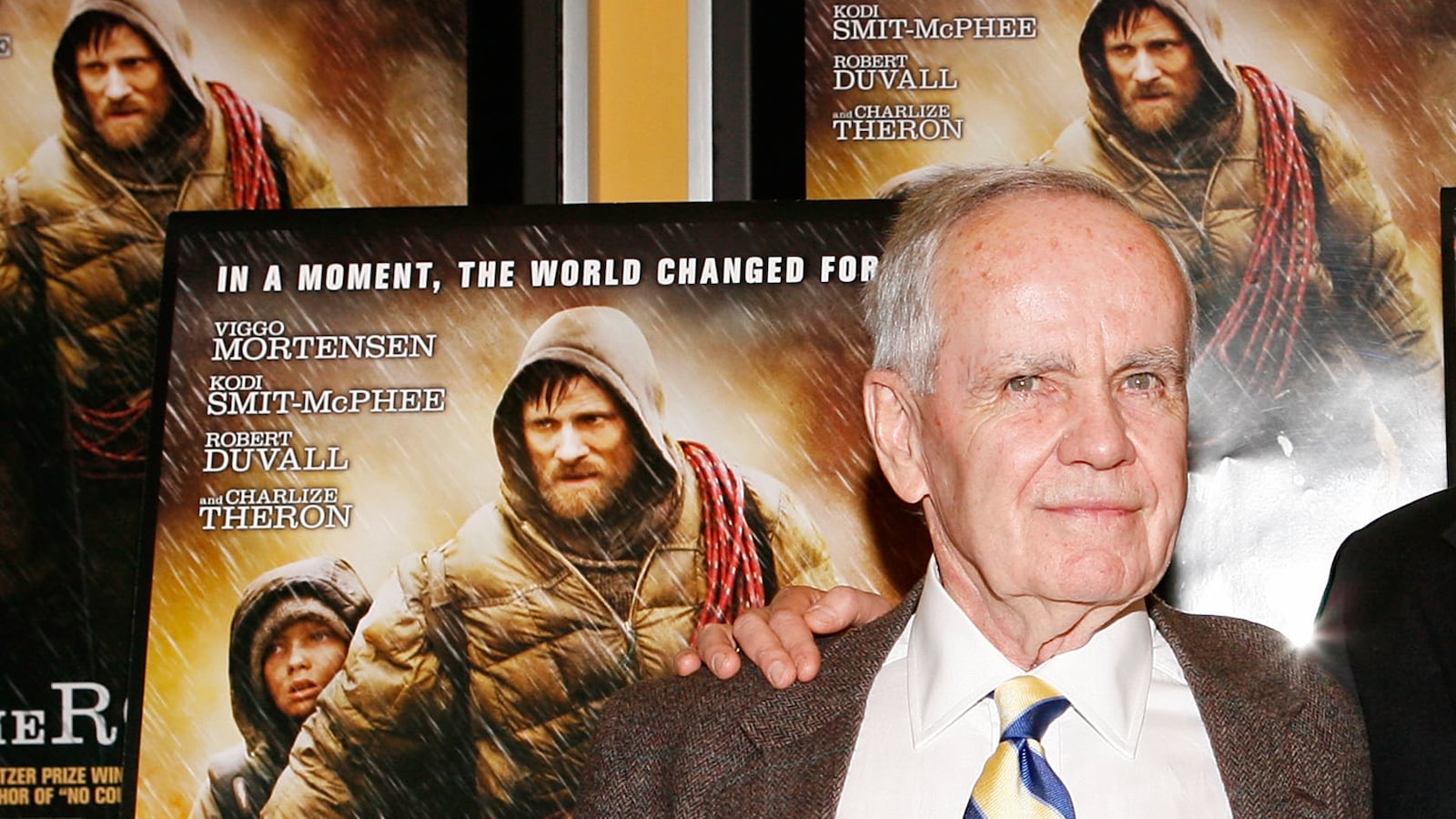

McCarthy’s new novel, The Passenger, is a sort of test for these grand ambitions. The book does indeed encompass a wide range of disciplines and interests: the abstrusities of particle physics and modern mathematics, the nature of hallucinations and reality, the influence of the atomic bomb on the 20th century, and much more. It’s an imposing achievement and a testament to nearly nine decades of inquiry by a brilliant mind. While its aesthetic success is shadowed by some flaws, The Passenger is a powerful and thought-provoking distillation of many of the genres and ideas that have obsessed McCarthy throughout his career. There are lyrical evocations of nature reminiscent of The Border Trilogy, elements of sinister thriller straight from Νo Country for Old Men, moments of death-haunted solitude that recall The Road, and a comic cataloging of deviants and misfits that revives the riverside anthropology of Suttree. Like all of his earlier fiction, the new novel is also permeated by a constant awareness of the finitude of human life and the permanent oblivion that follows it.

The book’s kaleidoscopic compression of sensibilities and subjects constitutes a new aesthetic in its own right. One good analogy for its nature comes from a character in the novel who, sitting in a New Orleans restaurant, gives a deadpan description of the secret to the perfect cooking broth: “Unless you have an old rancid stockpot that you can just sort of throw every horrible thing into—rotten turnips, dead cats, whatever—and let it simmer for about a month—you’re at a real disadvantage.” The Passenger is something like McCarthy’s own rancid stockpot: he has tossed in a romance between siblings, tormenting mental hallucinations, nuclear weapons, speculations about consciousness, physics, and history, a bit of possibly justified political paranoia, and a host of minor eccentric characters. He then let it simmer, by some accounts, for around 20 years. The result is a brew that’s rich and strange, but it’s definitely an acquired taste.

The story centers on the siblings Bobby and Alicia Western. For reasons that are never entirely clear or plausible, they are haunted by a forbidden passion for each other. Their father was a physicist who worked on the development of the first atomic bombs, and both children are highly gifted in physics and math. Alicia is by any standard a genius, a mathematical prodigy who becomes a doctoral candidate in the subject at the University of Chicago while still a teenager. Bobby does some graduate work in physics at Caltech but leaves the discipline after realizing that he’s not good enough to do it “at the level where it really mattered,” which seems to him to mean changing the field.

When the book opens, Alicia is dead, and Bobby is working as a salvage diver, descending into lightless depths to recover goods and bodies from wrecked ships and planes. One job takes him to a sunken plane from which a passenger’s body seems to be missing. By the flare of a torch, he beholds the faces of the dead, “Their mouths open, their eyes devoid of speculation.” It’s a macabre nocturnal scene reminiscent of the opening of No Country for Old Men, but here the description of the bodies ends with a note of carnivalesque humor. “They were all swollen in their clothes and you had to cut them out of their seatbelts. Quick as you did they’d start to rise up with their arms out. Sort of like circus balloons.”

The word “dark” doesn’t begin to capture the grimness of the novel’s humor. Asked by a detective whether a man who has just committed suicide was a troublemaker, the waitress at a bar he frequented replies: “All I can say is that he never done nothin like this before.” Another character, staring out the window at the frozen bleakness of a Chicago winter, remarks, “Life. What can you say? It’s not for everybody.”

This cheerful insight issues from the mind of a character who technically does not have one: he exists as a persisting phantom in Alicia’s brain. Called “the Kid” or “the Thalidomide Kid,” he appears to her with all the vivid, irrefutable reality of beings with more traditional ontological credentials. Diminutive of stature, with flippers instead of arms, prone to inane puns and foul-mouthed abuse, the Kid also harbors dark metaphysical depths and likes the esoteric terminology of particle physics. He’s a sort of impresario of strange beings and disturbing apparitions, presiding over a surreal vaudeville that plays unbidden in Alicia’s mind. His entourage includes “A matched pair of dwarves in little suits with purple cravats and homburg hats. An ageing lady in pancake makeup smeared with rouge. Antique dress of black voile, graying lace at throat and cuffs. About her neck she wore a stole assembled out of dead stoats flat as roadkill with black glass eyes and brocade noses.”

McCarthy’s earlier novel Blood Meridian also featured a character known only as the Kid and marauding bands attired in outlandish and ghastly garb, but here the apparitions dwell only in the mind. This represents a kind of bleak, absurdist twist on the old philosophical metaphor of the theater of consciousness. It also lets the novel question whether even the normal representations of the human mind are a species of hallucination. As the Kid says, “It’s all a murky business anyway. Take a bunch of stills and run them tandem at a certain speed and what is this that looks like life? Well, it’s an illusion.”

The dead are another category of beings who exist only in the minds of the living. After her suicide, Alicia persists in Bobby’s memories and sometimes shows an uncanny knowledge of his mind, just as her phantoms seem to derive information from her own unconscious. “Sometimes at night when he would try to tell her about his day he had the feeling that she already knew.” Some of the book’s most beautiful passages evoke this fragility of the dead, beings on the verge of oblivion who take temporary shelter in the minds of those who loved them. “He knew that her lovely face would soon exist nowhere save in his memories and in his dreams and soon after that nowhere at all,” McCarthy writes of Bobby.

The story’s early tension gradually slackens throughout the novel. It’s not a thriller in the mode of No Country for Old Men or McCarthy’s more recent screenplay, The Counselor. The novel drifts instead into episode and digression, leaping between subjects and styles freely. In one scene we hear Bobby riffing on what Kant might think of quantum mechanics (“that which is not adapted to our powers of cognition.”) In another, one of Bobby’s friends muses on a different sort of imponderable: “do you think if you died drunk you’d sober up before you met Jesus?”

Like Shakespeare’s Prince Hal, Bobby is a gifted son fleeing the legacy of a powerful father by mingling with charismatic drunks and wastrels. The Falstaffian jests and antics of Bobby’s friends form a sort of rowdy counterpoint to his own haunted solitude. They also give a necessary touch of color and levity to an aesthetic canvas that is otherwise bleak and spectral. Any throne to which Bobby eventually ascends is purely existential, a realm of cosmic loneliness dominated by the certainty and permanence of death.

In some ways the novel feels like McCarthy’s most autobiographical work yet. Bobby and McCarthy have quite a bit in common: a childhood in Tennessee, a stretch living in Ibiza, a deep knowledge of modern physics and mathematics, and a storehouse of gossipy anecdotes about their major figures. McCarthy has also mentioned the very short list of novels he considers truly great, and Bobby seems to share this aversion to a good deal of excellent literature. At one point he is squatting in an abandoned farmhouse with reading material that consists of “Victorian novels that he hadn’t read and wouldn’t but also a good collection of poetry and a Shakespeare and a Homer and a Bible.”

It’s tempting to wish that Bobby—and perhaps McCarthy—had absorbed more of the psychological nuance and depth of the best Victorian novelists. It’s hard to find plausible Bobby’s sudden romantic love for his sister, for instance, which is baldly stated in a few short, maudlin phrases: “he knew that he was lost. His heart in his throat. His life no longer his.” For all of McCarthy’s fascination with the nature of the mind, this moment, at least, does not feel like a particularly convincing depiction of one. George Eliot might be worth reading after all.

It’s also hard not to see a tension in some of the novel’s epistemology. At points there is an unremitting skepticism about the possibility of knowing anything. The Kid says of Alicia, “She knew that in the end you really can’t know. You cant get hold of the world. You can only draw a picture. Whether it’s a bull on the wall of a cave or a partial differential equation it’s all the same thing.” At other points, however, there is a strong certainty about reality. As one of Bobby’s friends says, “The world’s truth constitutes a vision so terrifying as to beggar the prophecies of the bleakest seer who ever walked it.”

These are ideas expressed by characters, one of whom is a hallucination, and various bits of dialogue in a novel shouldn’t be expected to meet standards of philosophical logic. But both of these claims can’t be true. A world in which we can’t really know is not one in which we can assert that the truth of reality is so terrifying as to beggar the prophecies of the bleakest seer. If all our mental phenomena are untrustworthy, any conviction about the world’s unknowability or terror is itself uncertain.

But this fundamental bleakness is an axiom undergirding all of McCarthy’s work. Whatever its philosophical merits, the worldview yields powerful aesthetic results. He’s a brilliant registrar of fundamental human perplexities: our simultaneous awareness of the world’s beauty and our intimations of its final loss, our yearning to understand the structure of reality and our incapacity to do so in a satisfactory way. Despite moments of radiance and humor, The Passenger suggests that the ultimate fate of the world and all its creatures is total extinction. What Bobby says after visiting his grandmother seems to be McCarthy’s view of humanity’s lot as well: “A few more years and his grandmother would be gone and the property would be sold and he would never come here again. The time would come when all memory of this place and these people would be stricken from the register of the world.”