By Maziar Bahari and Reza HaghighatNejad

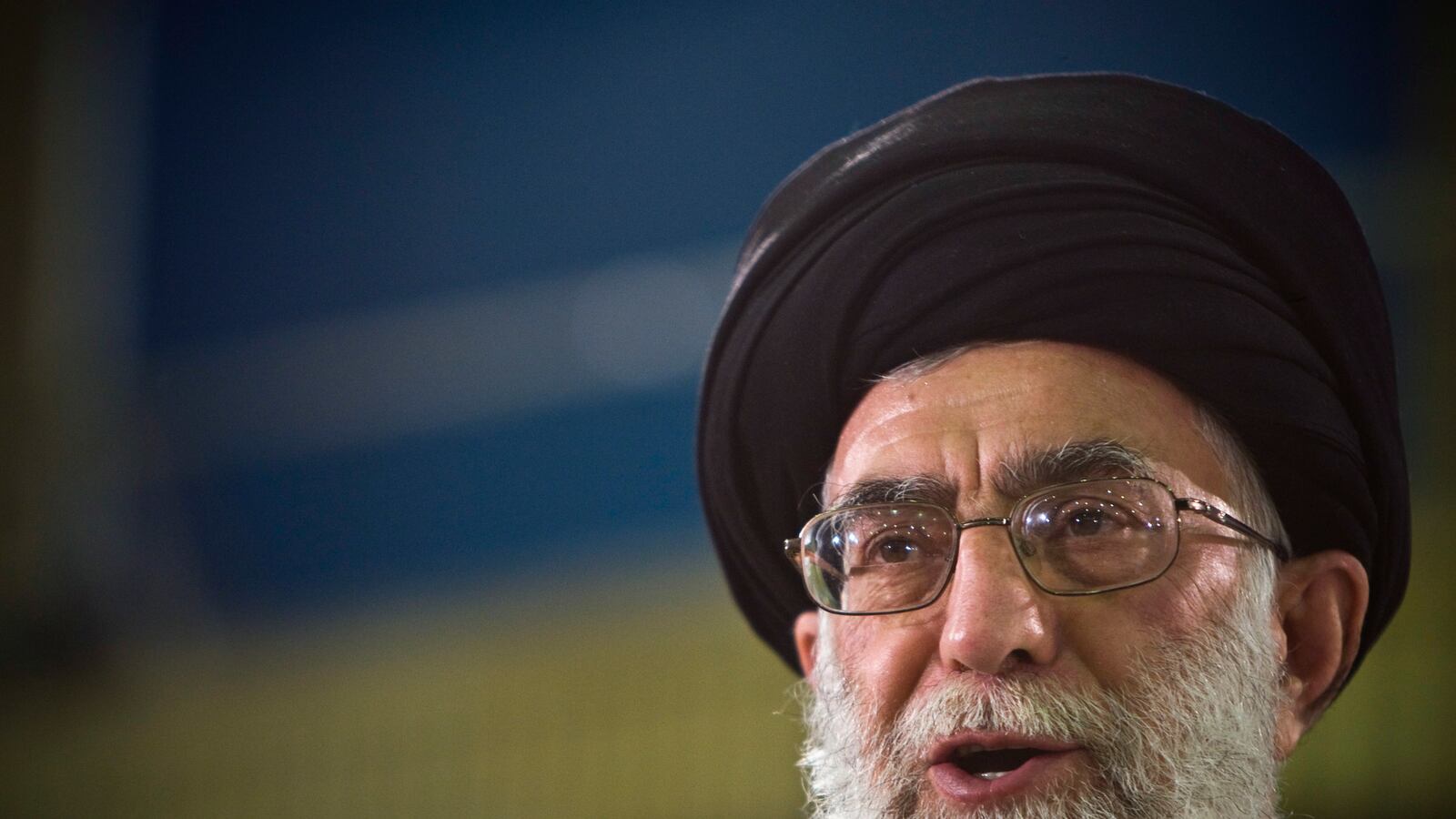

Every few days a crowd gathers at the Leadership Complex in central Tehran chanting “Death to America” and “Death to Hypocrites.” The group varies in size: sometimes there are hundreds of people, and other times only a handful. Supporters range from prominent government officials to farmers from remote villages. But everyone who attends these ritual gatherings is rewarded in some way. It might be extra food rations or a higher government position. People at risk of losing their jobs might be told their positions are now secure. What’s important to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is to have his supporters there with him, lending further legitimacy to his words. Whatever they may be.

Last week, during a ceremony attended by Iranian judges and prosecutors, Khamenei expressed his doubts about Iran’s potential cooperation with the United States in Iraq. He accused the American government of exploiting the advances made by extremist Sunnis in Iraq to gain control over the country. As his audience sat before him, many of them crossing their hands over their crutches or their chests—a very Iranian sign of submission—Khamenei said that the current crisis had nothing to do with the sectarian divide between Shia and Sunni Muslims. The crowd chanted on cue. The Ayatollah added, “Americans are trying to undermine the stability and the territorial integrity of Iraq, in which the last remnants of Saddam Hussein’s regime are used as proxies and those formerly outside this network of power are treated as pawns.”

Khamenei’s words were echoed by his supporters, who see the rise of the extremist Sunni group Islamic State of Iraq and the Sham, ISIS, as an important threat to Iran’s dominance in Shia-majority Iraq.

“After the victory of the Shias in Iraq, Arab countries, America and Israel started causing trouble because they were not happy with a Shia democratic government in Iraq,” said Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, former Chief Justice of Iran. “The people of Iraq should remain united,” he said. “Only the U.S. would benefit from a split.”

Shahroudi’s comments are particularly important because he was born and raised in Iraq, and was among the leaders of the opposition against Saddam Hussein. He is also widely regarded as Khamenei’s mentor.

Khamenei’s supporters call Khamenei “The Leader of All Muslims around the World,” and the gist of their conspiracy theories is that the whole world is united to undermine Khamenei’s leadership.

The U.S. presence in Iraq and the region is regarded as the main challenge to dominance in Iraq, but they also include ISIS in an American scheme against Iran. “Command centers for the ISIS fighters were in the White House and Saudi Arabia,” said a revolutionary guards commander who is a Khamenei appointee. “The ISIS conflict is an American and Zionist conspiracy to reverse Islamic awakening in the Middle East,” added another appointed commander.

There are widespread rumors and reports that Iran has already established a military presence in Iraq. An Iranian diplomat who did not wish to be named told IranWire that Ghasem Soleimani [also spelled Qassem Soleimani], the commander of the Guards’ foreign operations, is in Iraq coordinating the Shia response. The New York Times reported that Iran has deployed reconnaissance drones and military equipment to the Iraqi army. Iran’s foreign ministry denied both reports.

The foreign ministry is run by reformist figures close to President Hassan Rouhani, who was Khamenei’s least favorite candidate during last year’s presidential election. Khamenei’s supporters particularly objected to Rouhani’s friendly approach to the West during his tenure as nuclear negotiator in the early 2000s, and they now accuse him of trying to use the ISIS crisis to get Iran closer to the U.S.

There has, of course, been widespread interest in how any cooperation between Tehran and Washington might affect nuclear negotiations between Iran and the 5+1, the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany. President Rouhani’s chief of staff Mohammad Nahavandian said that if any cooperation in Iraq is to take place, the U.S. must first show its good intentions in nuclear negotiations. Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif welcomed the American approach for fighting terrorism as a common goal. Rouhani’s vice president tweeted that Iran and the US are the only two countries that can solve the Iraqi crisis in a peaceful manner.

But it’s not only Iranian officials that have been butting horns over ISIS. In Washington, Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham disagreed on whether Iran and the U.S. should work together. McCain viewed the possible partnership as “the height of folly,” while Graham believed the U.S. should “work with Iran to save Iraq.” On CNN’s State of the Union broadcast he said, “We should have discussions with Iran to make sure they don’t use this as an opportunity to seize control of parts of Iraq.”

These “mixed signals from Washington,” as Iranian officials call them, worry Iranian reformists—and are eagerly received by Khamenei. When in 2002 George W. Bush described Iran as part of the “Axis of Evil,” Ayatollah Khamenei attacked reformists for having cooperated with Americans in the 2001 multinational Bonn Conference on Afghanistan, saying that Americans had exploited Iranian help.

Foreign Minister Zarif has also criticized Washington’s failure to honor its commitments, citing the hostage crisis in Lebanon in the 1980s, when the U.S. promised to lift bans on Iranian assets if Iran helped secure the hostages’ release. When three of the American hostages were freed, the U.S. did not fulfill its promises.

Tehran and Washington differ on how to deal with Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, both immediately and as part of a future political compromise. Both reformists and hardliners in Iran agree that Maliki must be supported, and Rouhani has said that those who lost in Iraq’s elections were now trying to win by resorting to terrorism. Iran is, of course, not as supportive of the Iraqi prime minister as it is of Syrian President Bashar Assad, but even its half-hearted support could lead to a serious disagreement with other countries over hammering out a political compromise to end the crisis.

Khamenei is still very much in power in Iran. He remains very suspicious, and fearful, of the United States’ motives and intentions in Iraq. But by all accounts Khamenei is a pragmatic politician whose own survival is his first priority. So while an overt cooperation between Iran and the United States is unlikely, the ayatollah may recognize that in the short term the group of fanatics known as ISIS pose a more immediate threat to his dominance in Iraq than the U.S. does. In these terms, it’s important to remember that, for Khamenei, although the enemy of his enemy may not exactly be his friend, he can definitely have an affair with them. And he doesn’t have to tell the chanting crowd in the room about it.

This article was adapted from one that first appeared on IranWire.