This is part of our weekly series, Lost Masterpieces, about the greatest buildings and works of art that were destroyed or never completed.

I can still remember the first time I saw active oil derricks along the side of the highway in Los Angeles. My head snapped quickly away from staring down the taxi meter for a double-take, convinced I had just seen a movie set rather than one of the roughly 3,000 active oil wells in the city that stand as a reminder of oil’s part in its history.

Los Angeles hasn’t always been a one-industry town, and many of its richest denizens made their fortunes in the oil industry (see the Getty family or the Clampetts).

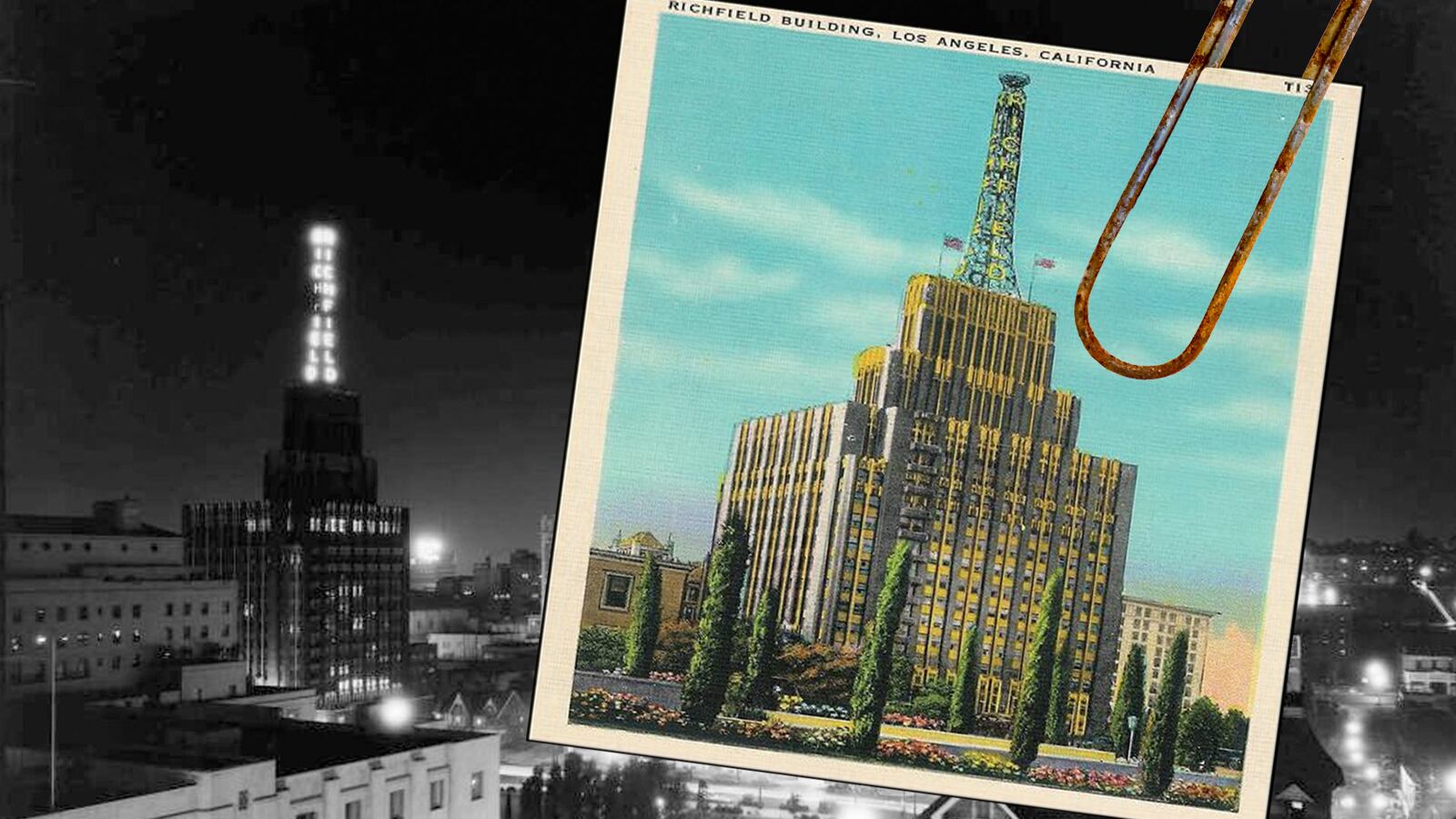

Even the city’s skyline was once dominated by an iconic reminder of that industry’s prominence—the Richfield Tower.

Subtlety has never been a character trait for those who made their wealth in fossil fuels, and the Los Angeles headquarters of Richfield Oil at 555 S. Flower St. was no exception.

Completed in 1929, it towered over the city at 372 feet (only City Hall was taller). The jazz moderne 13-story tower was clad in a mosaic of black terracotta and gold leaf, a reference to the “black gold” that was oil. According to a Nov. 13, 1968, article in the Los Angeles Times, what caused “most of the comment about the building and made it an unforgettable landmark here was the color scheme, black and gold.”

It was graced by a 130-foot tower inscribed vertically with the Richfield name in neon tube letters, each about 8 feet in length.

The tower, which was used as a beacon for planes, was designed to look like an oil well gusher. While most of the building comprised offices for the company, the 12th floor “housed a large amusement room, with stage, kitchen, cafeteria, barber shops, lavatories, and a ladies’ lounge.”

The tower saw little in the way of drama in its lifetime, except when a leaser for the company, Dudley Eugene Brown, threw himself from the 12th floor on Aug. 30, 1950. He hit one of the ornamental promontories on the 10th floor before falling again to the crowded street.

“At first I thought it was some gag. It looked like a dummy or something,” Sheriff’s Deputy Rex Jaenisch, who saw the fall, said to the Los Angeles Times. “He was spread-eagled, face down.”

The architect was Stiles O. Clements, who also designed the Pellissier Building, the El Capitan Theatre, the Mayan Theater, the Beverly Hills High Swim Gym (of It’s A Wonderful Life fame), and Robert Pattinson’s recent digs.

Clements has a fascinating backstory,. Originally from Maryland, he attended both MIT and the famed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. But he would become famous for his versatility, designing buildings in styles that included “Spanish Colonial, Mayan Revival, English Tudor, Beaux Arts, Art Deco, and Streamline Moderne.”

What nearly all his works had in common (as anybody who has seen the Mayan Theater can attest to) was an ornateness that stood out even in L.A. He had, wrote the Los Angeles Times, a “knack for designing lavish buildings.”

The tower, according to his daughter, was his personal favorite.

According to the building’s obituary in the Los Angeles Times in November of 1968, when Richfield was opened in 1929 “there were people who ridiculed it because it was different from downtown’s humdrum buildings of that era. They viewed its gaudiness as a shallow attempt to express and symbolize.”

Despite all the pearl-clutching, after shaking Los Angeles both in the architectural community and in its skyline, the tower would stand as a landmark for nearly four decades.

Sadly, that ambivalence also hastened its downfall. If contemporary coverage by the Los Angeles Times is to be believed, the only real opponents of the tower’s destruction were students of architecture, “but their pleas created only ripples, not waves.”

By the late 1960s, the building was considered obsolete. According to company officials, the building was only 54 percent useable, meaning, wrote Ray Herbert for the Los Angeles Times, it was “obsolete—in floor layout, elevator service, air conditioning, the quantity of its utility distribution systems” and other issues.

More importantly, while the tower offered up 120,000 square feet of office space, if it was destroyed along with surrounding buildings, a new complex of more than 2 million square feet was feasible.

Thus the tower did not have its fate sealed in solitude. It was torn down along with a nearby IBM building, an apartment complex, a car-rental building, Dawson’s Book Store, and the 11-story Douglas Oil Building—to make way for what its owners described as “a Rockefeller Center-type complex.”

The demolition alone cost an estimated $1 million.

“We’re planning to tear it down with tears in our eyes,” Louis M. Ream Jr., a Richfield executive, said at the time.

The “Rockefeller Center-type complex” was completed in 1972 as the ARCO Plaza twin towers (now known as the City National Plaza). Topping out at 52 stories, they were the tallest towers in the city (for one year).

For a while, at least, the location continued to be prominent, as it was sold in 1986 for a Southern California record $650 million. Today, they are the second-tallest twin towers in the U.S., after the Time Warner Center in New York City.

But the ’90s and early 2000s were rough for the property—by 2003 two-thirds was empty. The dull giant island skyscrapers of midcentury America were out of fashion.

It was only fitting, then, that the man who was hired in 2003 to oversee the building’s redesign told the Los Angeles Times he was inspired in his plans to play with light by his “memory of visits to downtown as a child in the 1950s, when he was dazzled by the sign on the old Richfield building that spelled out the oil company’s name.”

Part of the plan included laser light shows between the buildings at night. The towers are still a big part of the Los Angeles skyline (the 10th tallest in the city), and the makeover seems to have worked as it attracted the L.A. office of hip architectural firm Gensler and made news for recently being turned into a 700-foot harp.

But it’s hard not to feel like all the remodeling and makeovers are compensating for something. Black and gold and jazz all over: The original did it best.