Salaciousness sells today just like it always has, which is both the subject and the reason for the existence of Dark Side of the ’90s, Vice TV’s docuseries spin-off from their successful wrestling effort Dark Side of the Ring. Premiering on July 15, it’s a look back at some of that decade’s most notorious and influential stories, shining a spotlight on the downside to the era’s infatuation with outrageousness, even as it enthusiastically revels in it. Censuring the very thing it’s celebrating, it’s a fundamentally hypocritical venture—which doesn’t mean it has nothing to say about its chosen subjects.

Narrated by Sugar Ray frontman and former Extra host Mark McGrath, Dark Side of the ’90s kicks off with a one-hour episode that revisits a seminal ’90s movement: the explosion of daytime TV talk shows dedicated to pushing the envelope past its breaking point. At least initially, Oprah Winfrey and Phil Donahue ruled the airwaves with programs dedicated to an even-tempered mix of social and entertainment topics. Yet as the series smartly contends, things took a downward turn courtesy of Geraldo Rivera, first when he opened up Al Capone’s vault and found nothing during a heavily hyped syndicated special, and then when, during an episode of his talk show Geraldo, a brawl broke out between neo-Nazi and Black guests, earning the host a broken nose. Both were empty spectacles—the former resulting in no payoff, the latter a shameless fiasco—but since they drew enormous ratings, they soon became the guiding template for the industry.

Enter Jerry Springer, the former mayor of Cincinnati, who had left office thanks to a scandal involving paying prostitutes with personal checks and who was hosting a staid Donahue rip-off in his hometown. Going nowhere fast, the show moved to Chicago, where Richard Dominick became executive producer. Realizing that cancellation was on the imminent horizon, Dominick decided to go for broke and cross every boundary in search of eyeballs. Men who married horses, porn stars who performed historic gang bangs, and friends and lovers who were ready to beat each other senseless soon became the norm for a typical hour of The Jerry Springer Show. It was a cavalcade of trashy, tawdry, tabloid insanity, and America ate it up—as did Springer’s rivals, who soon turned copycat in an ever-escalating war to garner attention through sheer, unadulterated classlessness.

Just as many media types did, Dark Side of the ’90s reasonably points the finger at Springer for coarsening American culture. The problem, of course, is that this episode’s entire hook is its countless scenes of Jerry Springer mayhem, and the vicarious thrill that one gets from hearing others discuss, critique and decry it in florid language. To add to the episode’s own combustible mix, Dominick embraces his role as the de facto godfather of this trend, which he jokingly refers to as “the nightmare of television,” as well as defends the outlandish folks he put on air, who he claims, “Weren’t trash people. They were good people. These are good, solid people who came on the show and probably had more guts than half of the people out there who criticized them at the time.” Embellished by commentary from the likes of Montel Williams, the clips on display paint a somewhat different picture.

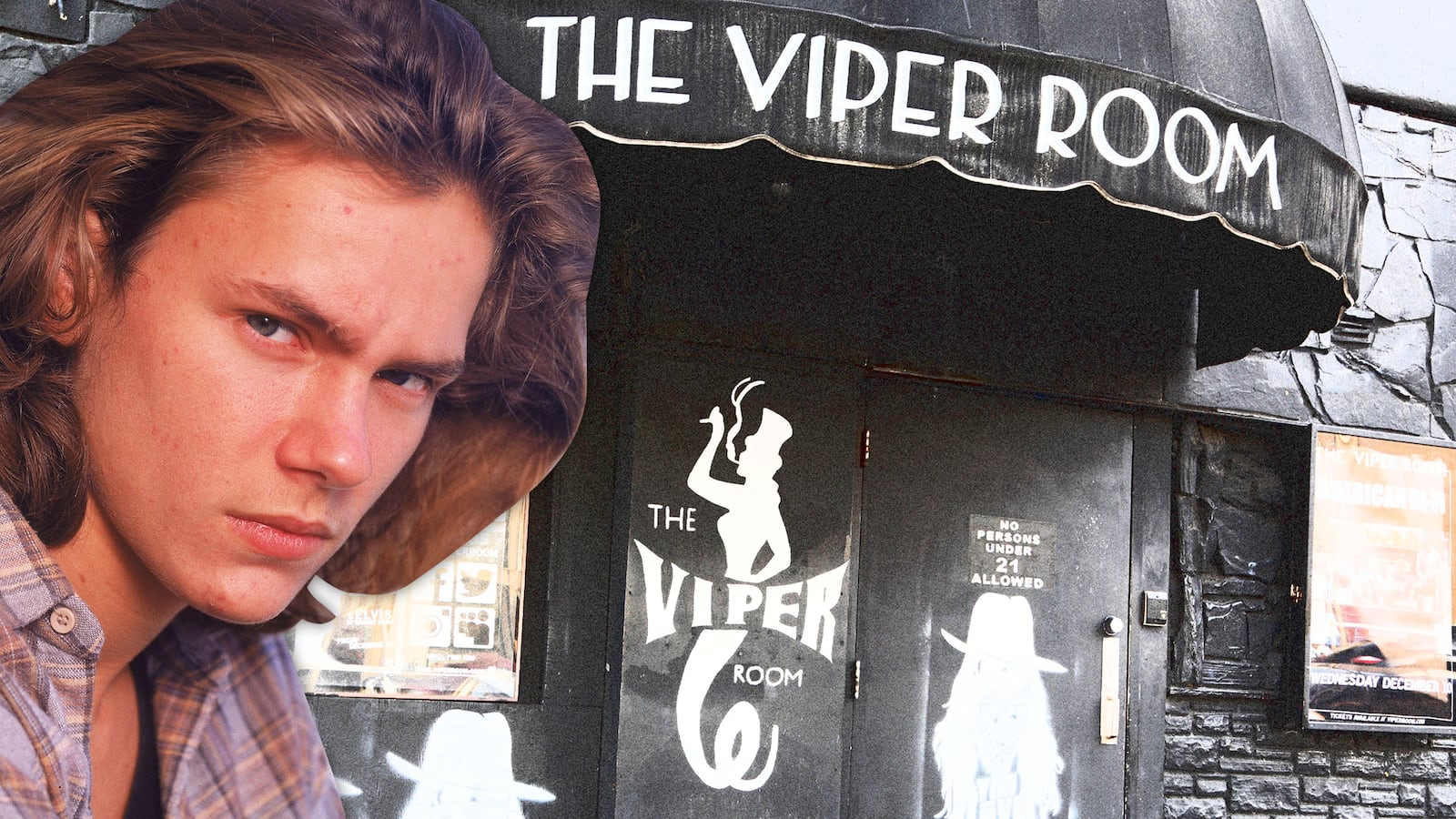

Jerry Springer’s freak-show lunacy was both its calling card and its eventual downfall, since you can only shock people for so long before the routine grows stale. The fleeting nature of cultural phenomena is also the prime subject of Dark Side of the ’90s’ second episode about the Viper Room, the trendy L.A. nightclub owned by Johnny Depp that served as the scene of River Phoenix’s fatal cocaine and heroin overdose on Oct. 31, 1993. The Viper Room’s rise and fall took place within the course of a few months, and the series captures the way in which such key moments in time rarely last—and, in fact, are probably doomed from the start to burn out quickly, and brilliantly.

As Dark Side of the ’90s explains, Depp purchased the Viper Room as a rock club that, because of its 200-person capacity, could function as an exclusive hangout for young Hollywood celebrities looking to escape the public eye—and, in particular, the incessant flashbulbs of the hungry-for-a-snapshot paparazzi. Counting Crows frontman Adam Duritz speaks candidly about his decision to flee his newfound fame by bartending at the Viper Room, making it his veritable second home and the spot where he’d meet then-girlfriend Jennifer Aniston. Copious photographs and video clips of Depp, Leonardo DiCaprio, Tobey Maguire, Christina Applegate and their compatriots convey the heady atmosphere of this insular A-list environment, which provided a measure of safety from the Hollywood storm in which these individuals had all found themselves.

Dark Side of the ’90s relies more on archival footage than on the excellent, mythologizing dramatic recreations that are its wrestling counterpart’s highlight. The result is a conventional dive into seedy material, driven by footage that’s been replayed innumerable times—including the fateful 911 call that young Joaquin Phoenix made on the night of his brother’s death. The series’ decision to rehash that agonizing audio feels like insensitive overkill, and once again leaves the proceedings engaging in the very sort of tabloid-y behavior that its own narratives invariably condemn. It’s often guilty of the things it’s investigating, although such confusion doesn’t completely get in the way of making the occasional smart point about how these seminal incidents and fads gave birth to today’s entertainment and media landscape—specifically, the reality TV that’s now the bread and butter of numerous cable networks and streaming platforms.

Subsequent episodes concerning Beanie Babies, teen television programming, The Source magazine (and hip-hop) and the rise of the internet will no doubt operate according to similar rules, thereby allowing the show—and its target audience—to have it both ways. What Dark Side of the ’90s would ultimately benefit from, however, is a greater roster of A-list talking heads and a bit more of the restraint that, its stories suggest, was desperately needed in the ’90s.