A story about religion, guns, militias, cults, wiretapping, fraud, murder and individual and communal sovereignty, Wild Wild Country couldn’t be more timely—even if the particulars of its story are crazily unique to itself.

Directors Chapman and Maclain Way’s six-part Netflix documentary series (produced by Jay and Mark Duplass) recounts a truly insane episode in recent American history, which will be well-known to those who lived through it and, given that it’s since faded from the country’s collective memory, will likely stun those who didn’t. No matter your familiarity with its subject, however, the Ways’ non-fiction effort functions as both an eye-opening expose and an even-handed (sometimes to a fault) look into a host of contentious issues Americans are still grappling with today, minus—at least for most of us—the free-love orgies.

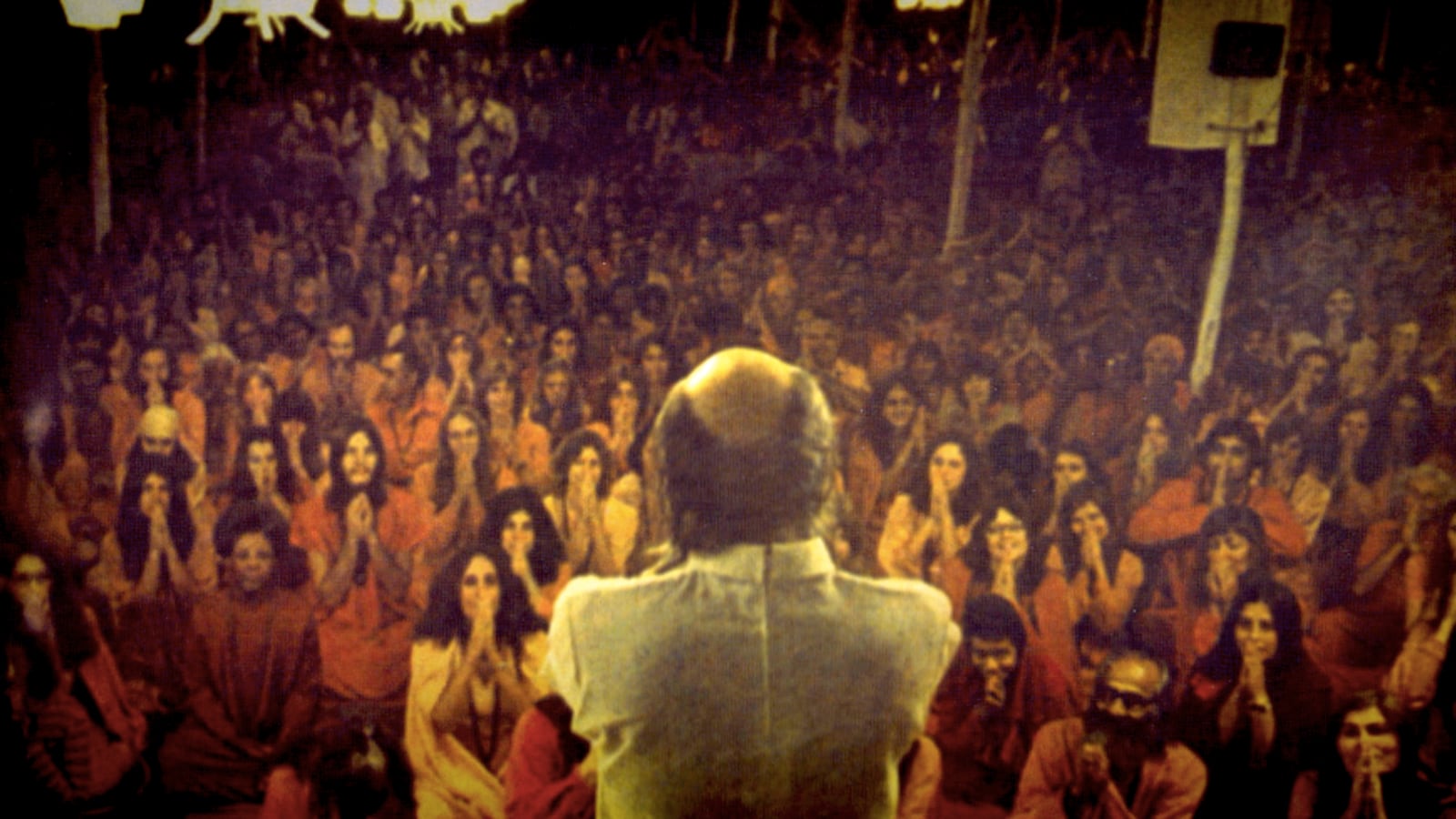

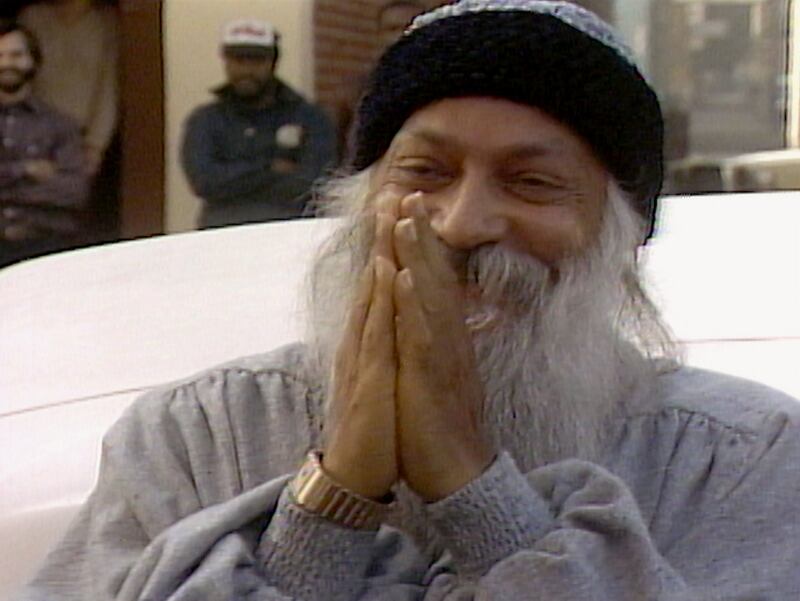

Capably assembled from hundreds of hours of archival footage, Wild Wild Country’s focus is the late Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, an Indian guru in flowing robes and sporting a Rip Van Winkle-style beard who, in the 1970s, created a New Age-y movement founded on ideas of peace, compassion and sexual inhibition. Many of his followers, known as “sannyasins,” came from the cream of the cultural crop, wore red clothes, and partook in meditation as well as other therapies involving lots of screaming, shuddering, and writhing about en masse. It was touchy-feely spirituality designed to spread across the globe and be easily marketable to consumers via retail books and international centers.

In 1981, having run afoul of Indian authorities, it relocated its epicenter to a 60,000-acre ranch in Wasco County, Oregon, right next to the tiny town of Antelope (population: 40), where it began construction on a city designed to be a paradise—and, also, a place where Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh could store his 19 (!) Rolls-Royces.

Antelope was a tiny enclave made up of elderly Christian retirees who prized their solitude and tranquility, so the influx of red-robed sannyasins and their “master,” Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (or “Osho”), wasn’t exactly welcome. A battle soon began brewing, with ranchers and farmers on one side, and Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s second-in-command, “secretary” Ma Anand Sheela (Sheela Silverman), on the other.

Sheela served as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s mouthpiece (since he went silent for a four-year stretch), and orchestrated the development of an independent metropolis known as “Rajneeshpuram” in Wasco County, replete with its own mail service and law enforcement. When long-time locals objected—including Bill Bowerman, the co-founder of Nike—and raised legal challenges to stymie this expansion, Sheela fought back by moving sannyasins into Antelope so they could take control of its municipal government through elections.

Then, she imported busloads of homeless people from around the country into Rajneeshpuram in an effort to further swell Rajneeshpuram’s ranks so they’d have enough voters to take control of Wasco County’s entire legislature. And when that plan failed, the surrounding area was suddenly, mysteriously struck by a plague of salmonella that made dozens violently ill.

Was this a case of a group exercising its constitutional rights to assembly, religion and representation, only to be persecuted by Christian bigots who didn’t approve of peaceful “others?” Or was it a takeover by an invading sex cult that was exploiting (and outright breaking) American laws in order to establish its own sovereign New Age nation? Wild Wild Country leaves those answers to the viewers, providing equal access to both sides of the debate.

On the one hand are those like Bill Bowerman’s son Jon and the McGreers, who fought alongside Antelope mayor Margaret Hill—and, later, those in the Oregon Attorney General’s office—to boot Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and company out of the state. And on the other hand are sannyasin publicist Sunny, disciple Jane Stork, lawyer Swami Prem Niren, and Sheela herself, who in new interviews paint their saga as one of discrimination and oppression—and ultimately, according to Swami Prem Niren, as a “tragedy.”

At the center of this entire affair is Sheela, a young Indian woman whose slight built and cheery smile belied her ferocity. As Wild Wild Country elucidates, Sheela’s dedication to her cause was second only to her lust for power. And the actions she took to maintain her coveted position beside Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh soon involved not only stockpiling an armory featuring more guns than were possessed by all of Portland’s police, but poisoning the surrounding populace in an act of bioterrorism, wiretapping her fellow sannyasins (in the largest such case in U.S. history), plotting to bomb a courthouse and assassinate the U.S. attorney for the District of Oregon, Charles Turner, and having Stork carry out a (botched) hit on Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s doctor.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

NetflixThroughout, the filmmakers give Sheela and her former cohorts ample time to characterize Rajneeshpuram as an innocent, enlightened enclave (a shining model of diverse people living in blissful harmony!) that eventually took reasonable measures to protect itself from extinction—only to be treated heinously by intolerant conservative Americans and the dastardly U.S. government. And to its credit, Wild Wild Country lets them raise a couple of not-unreasonable questions: Don’t religious groups have the right to congregate, even in enormous numbers? And what prevents such collectives from seizing control of their regional governments via the ballot box?

Wild Wild Country allows its speakers—Swami Prem Niren in particular—to consistently cry “victim” while proclaiming (through moved-to-tears waterworks) the holiness of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. The problem is, such arguments ring more and more false as we learn about the illegality, corruption and murderousness of the commune and its leaders.

In an effort to provide both sides of the story, the directors—especially in late, slow-motion-drenched elegiac passages full of uplifting and/or mournful music—buy too much of the pap being sold by the sannyasins. Their comments are often self-serving to the point of being laughable, and much of the happy-go-lucky video footage of life inside the commune is clearly propagandistic. Worse still, the Ways’ refusal to have Sheela now directly address her own wretched behavior—even after Stork has outright admitted on-camera that Sheela ordered her to kill Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s physician with a syringe full of poison—makes it feel like the directors are skirting obvious fundamental truths (and conclusions) in the name of “objectivity.”

No such equitableness, however, can obscure the fact that Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s commune—regardless of Antelope citizens’ prejudices—severely violated the separation of church and state, and participated in a wide range of crimes that eventually led to its downfall (this after Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh himself had a falling out with fleeing-from-justice Sheela).

As a portrait of militant zeal and religious conflict, Wild Wild Country is a fascinating glimpse at the perils of fanaticism-run-amok and the contentious intersection between faith and freedom—and it’s one that, in our current age of armed civilian slaughter and red state-blue state hostility, doesn’t seem as far in the past as one might like.

Wild Wild Country premieres March 16 on Netflix.